The Phillips Collection mourns the passing of Dani Levinas, Chair Emeritus of the Board of Trustees, and expresses its deepest condolences to his family, friends, and the Washington, DC, community he loved.

Dani Levinas in his Georgetown home. Photo: Rhiannon Newman

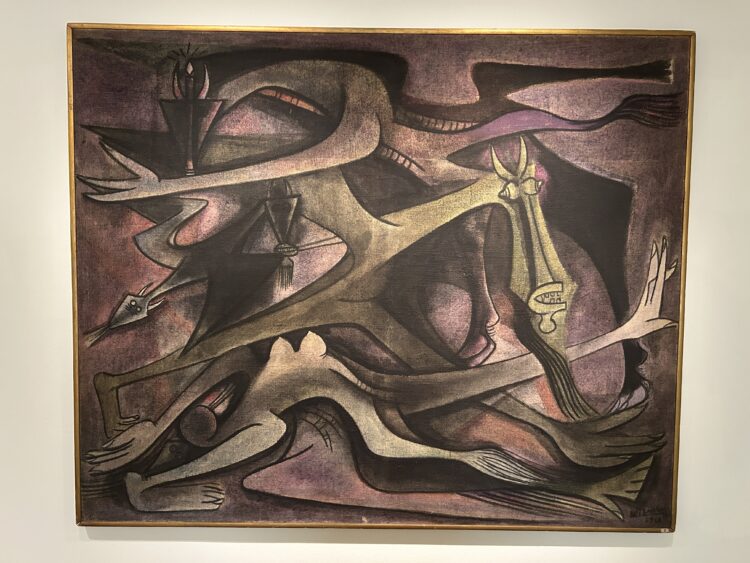

Dani, along with his late wife, Mirella, was a true advocate for contemporary art and experimentation. His extraordinary dedication and leadership during his tenure as Chair of the Board from 2016 to 2022, as the Phillips celebrated its centennial, helped the museum dramatically expand its focus on contemporary art, community engagement, and diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion. Like the museum’s founder Duncan Phillips, Dani was passionate about supporting living artists, collecting art of his time, and living with his art. This was evident by his art-filled Georgetown home and his recent book, The Guardians of Art: Conversations with Major Collectors—both of which he generously shared with the Phillips community. The Phillips was honored to host an intimate evening with Dani last October celebrating the launch of The Guardians of Art, which highlights the motivations, passions, and practices of major art collectors around the world.

Dani and Mirella Levinas at The Phillips Collection 2016 Annual Gala

Through his decades-long work as a collector, writer, publisher, and curator, Dani was particularly dedicated to contemporary Latin American art and artists. He connected the Phillips with Spanish artists Bernardí Roig and Daniel Canogar and Cuban artists Los Carpinteros, who, because of Dani’s generosity and vision, are now part of the museum’s permanent collection. He made an indelible mark on the Phillips by encouraging the museum to be more innovative, experimental, and global in scope.

With their travels and time spent living in Argentina, Spain, and Miami, Dani and Mirella were intimately aware of urgent social issues in the US and around the world. Dani’s support made possible the groundbreaking and expansive exhibition The Warmth of Other Suns in 2019, which shared poignant stories about global displacement. Dani also cared deeply about expanding access to art through technology and reimagining the role of cultural institutions by spearheading enhancements to the visitor experience.

Dani Levinas and curators Massimiliano Gioni and Natalie Bell at the opening of The Warmth of Other Suns: Stories of Global Displacement. Photo: Rhiannon Newman

“Dani was a crisp and intelligent thinker and a joyful and passionate advocate for contemporary art and artists. His network of friends, colleagues, and people who loved and appreciated him spans the globe,” says Vradenburg Director & CEO Jonathan P. Binstock. “Indeed, well before reconnecting with him in my role at the Phillips, like many, I saw Dani regularly at art events in global cultural capitals year after year. He was steadfast in his warmth and welcoming posture, and his eagerness to discuss all the latest developments in the art world and beyond. I learned a lot from Dani. He will be sorely missed.”

“Dani Levinas’s passion and enthusiasm for art by living artists will have an enduring impact on The Phillips Collection. We will truly miss his inspiration and guidance,” says Phillips Board Chair John Despres.