In this series, Phillips Manager, Archives and Library Resources Juli Folk and Digital Assets Librarian Rachel Jacobson explain the ins and outs of how archives work.

The previous “Archives 101” post introduced the concept of archival collections. Archives and special collections establish policies to guide what materials are accepted and preserved by an institution. Because every collection is unique and can include a variety of different materials, formats, and related information, they require varying levels of description, so the standards for archival organization are applied to best suit the needs of individual repositories. I will discuss the first few steps that occur after an archive is accessioned into a repository as a new collection, also understood as archival processing. In addition to including activities that promote preservation, processing also provides improved physical and intellectual access to the records. Generally speaking, during processing, materials are surveyed, arranged, described, and preserved for long-term storage with archival-quality housing.

Surveying the collection establishes an understanding of the contents of the collection and the physical state of the materials. During this step, it’s important to gather all contextual information (e.g., donor agreements, accession details, preliminary inventories) and prepare a standardized way to capture the details. The archivist will:

- • Count the boxes, volumes, and items

- • Review existing container labels

- • Confirm the materials appear as expected

- • Note any damage or special handling needs

- • Identify existing groups of related materials

These steps may also help identify missing components and will aid in gathering the information needed to write detailed historical/biographical notes.

After the survey is complete, it is time to create a processing plan that intellectually arranges the collection into Series, and, if necessary, Subseries, usually determined by subject, function, or form. Series filing systems may be geographic, chronological, or alphabetical and a collection can include only a single series or many series. Intellectual arrangement decisions are based on the state of the collection and the needs of potential users, who can include museumgoers, researchers, art historians, students, and teachers. Intellectual arrangement also relies on two fundamental archival principles stated below.

Provenance refers to the individual or group that created or collected the items and dictates that records of different origins be kept separate to preserve their context. Establishing provenance is key to creating accurate and helpful accession records.

Original order refers to how the collection was organized when it was brought to the repository for accessioning. It often indicates how the record creator(s) considered, maintained, and used the materials. If the original order is useful and meaningful, then retaining it preserves existing relationships and evidentiary significance that will be helpful to collection users. If the original order is non-existent or not meaningful, then an archivist will likely suggest a new arrangement to better serve future researchers.

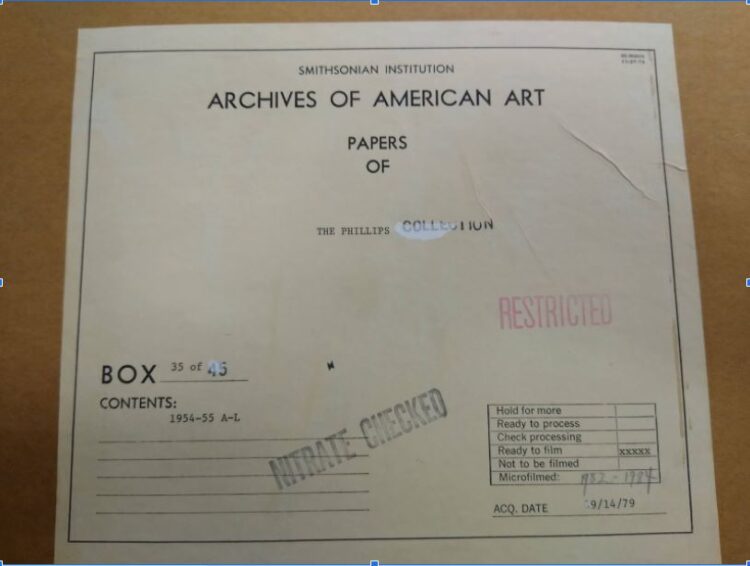

Before processing, the Duncan Phillips Directorial Correspondence was organized chronologically, in folders labeled only with the first letter for the correspondents within. This box contains all correspondence from 1954-1955 from individuals and businesses whose names begin with letters between A-L. Courtesy of The Phillips Collection Library & Archives.

This is an example where the original order was known but found to be unhelpful for users of the collection. As the label on the box describes, the original order of the Directorial Correspondence of Duncan Phillips was chronological and alphabetical by the correspondent’s name. However, this meant that a folder labeled ‘A’ would contain dozens of correspondents with the first letter ‘A’, making it difficult to pinpoint individuals. Therefore, it was determined that additional processing would help provide valuable information about individual correspondents. The arrangement is still chronological by correspondent, but individual correspondents have been separated into their own folder.

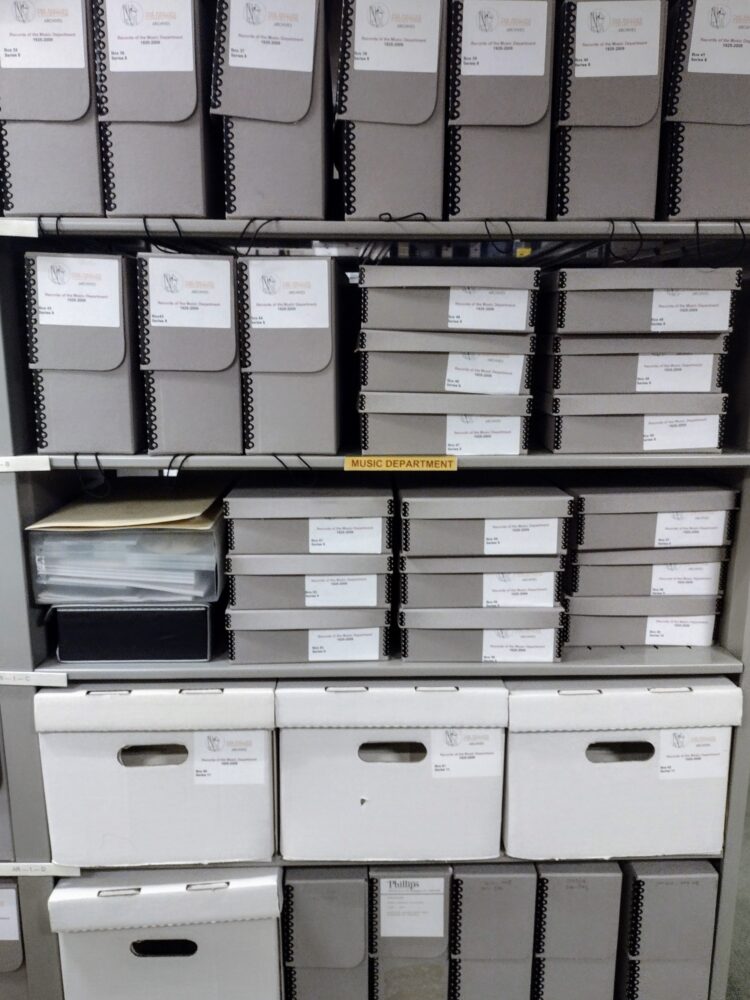

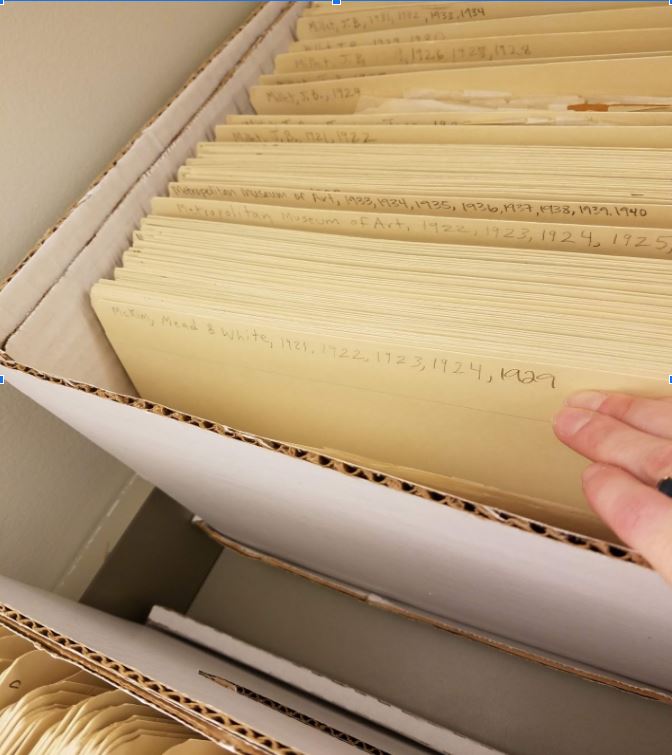

After processing, the Duncan Phillips Directorial Correspondence is organized alphabetically by correspondent, with multiple years arranged together, for ease of research. Courtesy of The Phillips Collection Library & Archives.

Surveying and arranging the materials provides all the information needed to describe the collection in a Finding Aid. Finding aids contextualize the materials and breadth of a collection, describing why it is important and unique. They contain detailed notes used by researchers to determine whether the contents of a collection may be useful to their research. We’ll discuss Finding Aids in more detail next!