We’ve partnered with STABLE arts, a studio complex in DC that provides visual artists with an active workspace. STABLE artists picked a permanent collection artwork and explain how it intersects with their own practice. Visit the Phillips Instagram for more STABLE artwork.

Andy Yoder (@andyyoderart)

What draws me to Christenberry’s photographs of buildings is their lonely emptiness, and in this image the faded advertisements add a layer of nostalgia. I grew up in Ohio, and these remind me of the Mail Pouch Tobacco ads I used to see on barns. Buildings and shoes are extensions of the people who use them, a quality that deepens as they become worn. After combining words and images from recycled packaging with hundreds of sneakers, I appreciate the skill of the sign painters, scaling their work to fit the wall with graceful precision.

Born in Cleveland, Andy Yoder attended the Cleveland Institute of Art and Skowhegan. His work is in numerous public and private collections, and exhibitions include shows at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Queens Museum of Art, Winkleman Gallery in New York, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Commissions include works for ESPN, Continental Airlines, Progressive Insurance, David and Susan Rockefeller, and the Saatchi Collection.

(LEFT) William Christenberry, Wall of Building with 5 cent Signs, Demopolis, Alabama, 1976/printed 2000, Ektacolor print, 8 x 10 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Lee and Maria Friedlander, 2002 (RIGHT) Andy Yoder, Bruce Lee Jordan 5

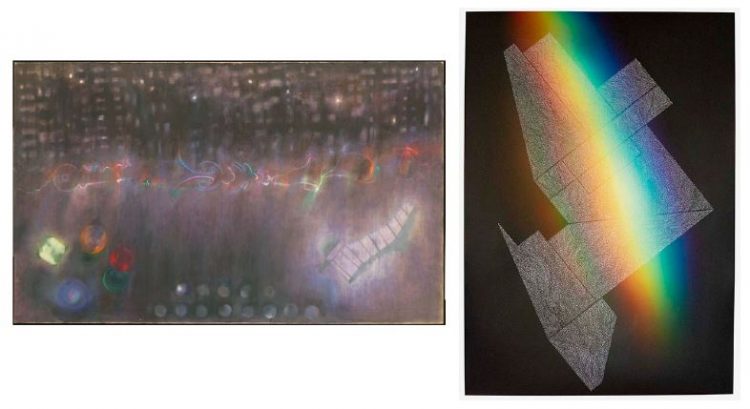

Caitlin Teal Price (@caitlintealprice)

Loren MacIver’s painting spoke to me because of her depiction of light and energy. With paint she is able to render the glowing light that you would capture with a camera. As a trained photographer I have always been attracted to the magic of light. In my current work I photograph rays of sun light. I then use an x-acto blade to draw into a photograph by scraping away the emulsion one line at a time. This technique reveals the white paper underneath, giving the piece enhanced energy and glow, much liked the piece New York by MacIver.

Caitlin works with photography and drawing to explore themes of ritual and routine found in the undercurrents of everyday life. Her work is included in numerous collections and she has been published in New York Times, New Yorker, and Time among others. Caitlin is the co-Founder of STABLE.

(LEFT) Loren MacIver, New York, 1952, Oil on canvas, 45 1/4 x 74 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1953 (RIGHT) Caitlin Teal Price, Dark Prism, 2019, 58 x 40 in.

Stephen Benedicto (@stephenbenedicto)

I have always appreciated bilateral symmetry and the way it often seems to elicit the human body. There are certainly parallels between the strength, weight, and sensuous nature of Barbara Hepworth’s Dual Form and my own work. It’s a dynamic work that draws me in and makes me want to interact with the shadows, form, and complex quality of material. That sentiment is always with me when making work.

Stephen Benedicto is a fine artist based out of Washington, DC. His art has been featured in commercial estates in the DC metro area and been acquired into private collections around the nation. His works have also been shown at a satellite event in Miami during Art Basel, Hemphill gallery, and the STABLE gallery in DC. Whether carved by hand into plaster with steel-rigged drafting tools, plotted with CNC machines, or rendered in 3D software, his work utilizes diverse systems and tools to express the complex ideas of fetishism, transhumanism, and the design of the self.

(LEFT) Barbara Hepworth, Dual Form, 1965/cast 1966, Bronze, height: 72 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired with the Dreier Fund for Acquisitions and additional funds from Natalie R. Abrams, Alan and Irene Wurtzel, and a bequest from Nathan and Jeanette Miller, 2006 (RIGHT) Stephen Benedicto, The Radius, 2018

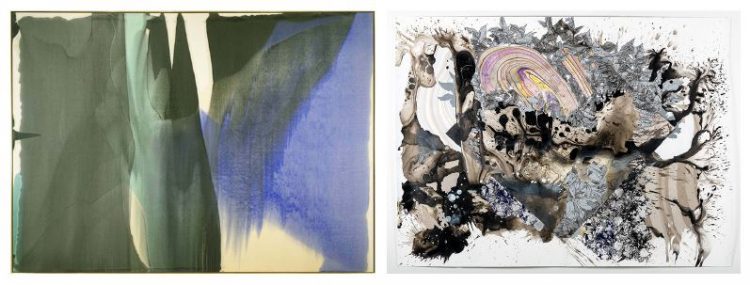

Tsedaye Makonnen (@tsedaye)

I chose Sam Gilliam because we are both Black artists based in DC and work in abstraction, however with different mediums. In this particular work his abstract acrylic painting is titled Mirror II, my recent abstracted light sculptures and textile works both use the material mirror acrylic. I’d like to think somehow through the use of the material mirror and the title mirror, our work is somehow a reflection of each other, literal and metaphorical… since Gilliam came before me and his work has influenced mine.

Primarily through sculpture and performance, my studio and research-based practice weaves together my identity as a daughter of Ethiopian immigrants and a black American woman. I explore the blurring between and transience of borders and identities, often using my body as the conduit and the material. Further creating new visual language that portrays our geographic and ancestral connectivity across manufactured borders and circumstances. As of late, my work is an abstracted participatory intervention that is both an intimate memorialization and protective sanctuary for black lives.

(LEFT) Sam Gilliam, Mirror II, 1979, Acrylic on canvas 80 x 80 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Scott H. Lang, 1981 (RIGHT) Tsedaye Makonnen, Aberash: You Give Light (and performance)

Tori Ellison (www.toriellison.com)

Over decades of museum and gallery visits, I keep coming back to Giacometti’s drawings and sculpture for inspiration. For this reason, I’ve chosen The Phillips Collection’s Giacometti Monumental Head. Giacometti carves, gouges, excoriates the surface, building and rebuilding the form to reveal an essence, an isolated psychic presence. The figure becomes less a portrait and more a totem, symbolic of the existential state of the human condition. In this series of my work, I’ve used the empty dress form to speak of the female body, returning repeatedly to see what it reveals to me. I relate to Giacometti in a kind of interiority expressed, a universal form utilized, and a psychological presence. It’s as if he’s looking inside the figure in sculpture. He said, “Photography, X-rays, and microscopes have allowed us to penetrate the secrets of matter [and] forced artists to paint something else, like their inner life.” At times I have worked with X rays to express the site of the body as ephemeral and connected to the natural world—here with the print Verso. I discuss my X ray art in Bettyann Kevles’s Naked to the Bone: Medical Imaging in the Twentieth Century, which became a TV documentary. I have also worked in stage and costume design, and I’m lately inspired by the Wolfgang Laib Wax Room and the Moira Dryer exhibition. Conceiving of the space of the body in new ways, through the stage, props, architecture, various enclosures intrigues me—these are new areas I’ve recently been exploring through installation. That said, The Phillips Collection, with works by Dove, Hartley, Ryder, Rothko, many others, has influenced me in so many ways—it’s very hard to limit it to just one artist to cite as most personally influential.

Tori Ellison, a MacDowell Fellow, School of Visual Arts MFA, NYC NEA finalist, and George Mason University art professor.

(LEFT) Alberto Giacometti, Monumental Head, 1960, Bronze 3/6 37 1/2 x 11 x 10 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1962 (RIGHT) Tori Ellison, Shell

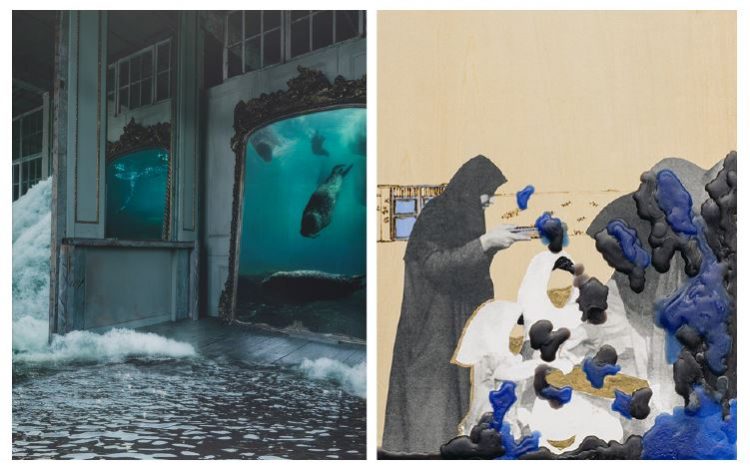

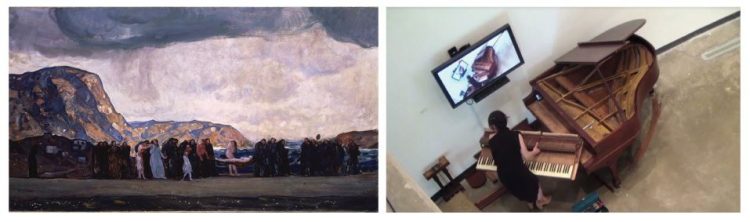

Emily Francisco (@emily.is.magic)

After losing his brother and father to the 1918 flu pandemic, Duncan Phillips acquired Burial of a Young Man. I first encountered Rockwell Kent’s somber funeral procession while working on Preliminary Deconstruction (or Preparing a Cenotaph), a durational performance about processing grief. Over a three-week period I carefully pulled apart an heirloom piano donated by the widow of its former owner. In exchange for the piano, small sculptures constructed from pieces of that piano were returned to the family. As we face a new global pandemic and uncertain future I am revisiting the intersection of these works and their relationship with how we process, share, and experience loss.

Emily Francisco is a sculptress specializing in the creation of interactive objects that generate sound. Born in Honolulu, raised in the lead belt, educated in Saint Louis and the District of Columbia—she exhibits work internationally and occasionally performs around Washington, DC.

(LEFT) Rockwell Kent, Burial of a Young Man, c. 1908-11, Oil on canvas, 28 1/8 x 52 1/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1918 (RIGHT) Emily Francisco, Preliminary Deconstruction (or Preparing a Cenotaph)

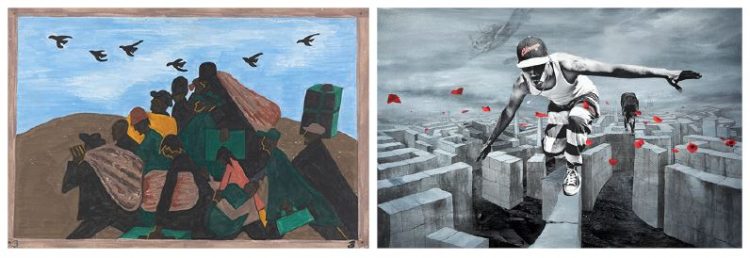

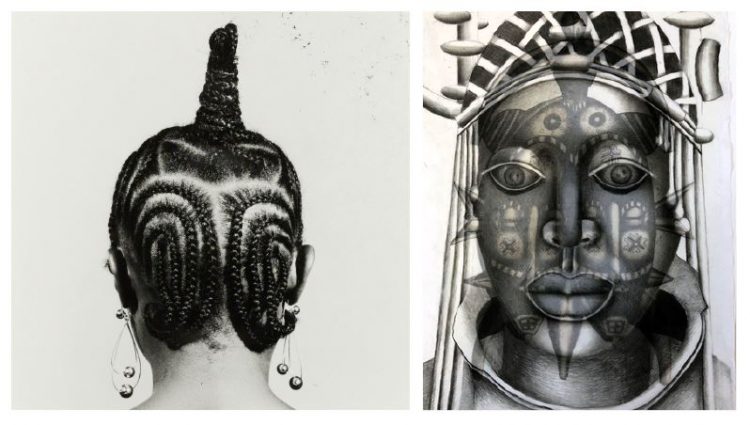

Gail Shaw-Clemons (@gshawclemons)

I was struck by J.D. Okhai Ojeikere’s portrait entitled Ife Bronze, an African photographer inspired by African hairstyles with references to the mask. Hairstyles found on masks continues today with black people all over the world even though many were taken away from their continent, country, and culture.

Gail Shaw-Clemons, born in Washington, DC, received her Master’s Degree in printmaking from the University of Maryland. She has exhibited extensively, with many works included in public and private collections in the US, Brazil, Norway, Sweden, China and Ireland. Shaw-Clemons is currently an adjunct professor at Bowie State University and is retired from the United Nations International School in New York.

(LEFT) J.D. Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Ife Bronze), 1972, Gelatin silver print, The Phillips Collection, Gift of Julia J. Norrell, 2018 (RIGHT) Gail Shaw-Clemons, Mask 3, 2020, Lithograph transfer on gel medium, 14 x 11 in.

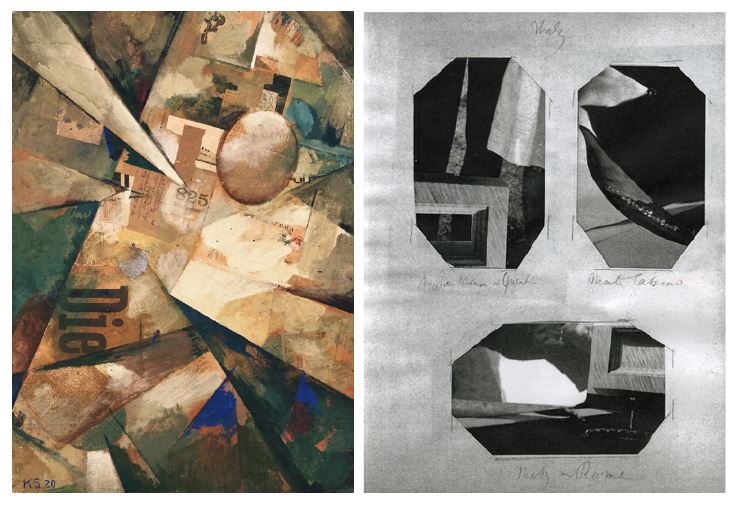

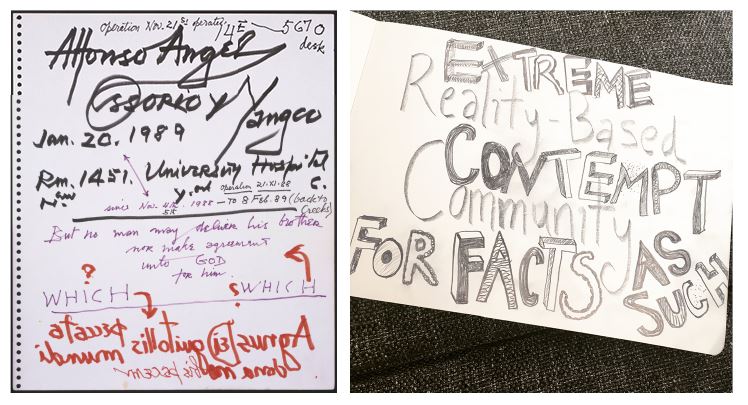

K. Lorraine Graham (@klorrainegraham)

Alfonso Ossorio created his 42 “Recovery Drawings” with markers and watercolor paper while in the hospital recovering from heart failure. I birthed my second child a few weeks ago, and the combination of pandemic time and newborn time has me considering, once again, the possibility of healing and reintegration inherent in every creative act—and what it means to make art under intense and shifting constraints. The Recovery Drawings remind me that limits can be be generative and that the wisdom gained from surviving trauma is potentially alchemical and transformative.

K. Lorraine Graham makes poems, drawings and sometimes performances. She is the author of The Rest Is Censored (Bloof Books) and Terminal Humming (Edge Books). From 2008-13 she curated the Agitprop Performance Series in San Diego and is also curator emerita of In Your Ear at the District of Columbia Arts Center. She works out of her post-studio in Stable Arts in Washington, DC, and writes about the arts and humanities for the University of Maryland, College Park.

(LEFT) Alfonso Ossorio, Recovery Drawings, Frontispiece, Book 1, 1989, Felt-tip watercolor marker on paper, The Phillips Collection, Gift of the Ossorio Foundation, 2008 (RIGHT) K. Lorraine Graham, Reality-Based Community

Stay tuned for Part III!