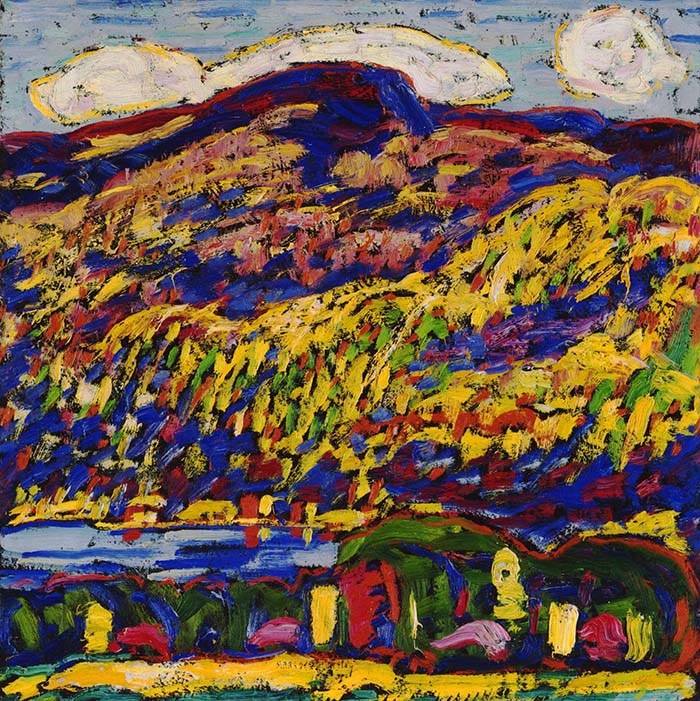

The Phillips Collection galleries have been dark and empty and our staff and visitors have been missing our beloved collection. In this series we will highlight artworks that the Phillips staff have really been missing lately. Media Relations Manager Hayley Barton on why she misses Marsden Hartley’s Mountain Lake—Autumn (c. 1910).

Marsden Hartley, Mountain Lake—Autumn, c. 1910, Oil on academy board 12 x 12 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Rockwell Kent, 1926

The first time I saw a painting by Marsden Hartley, I was an intern at the Bates College Museum of Art, in Lewiston, Maine, home for the summer to escape the heat of my college town, in Charleston, South Carolina. How fitting to see my first Hartley in the town of both his birthplace and my own. A few years later I found myself at The Phillips Collection, having recently moved to Washington, DC (again, to escape the heat of Charleston only to find myself in a swamp . . . womp). I turned the corner into a parlor in the historic Phillips House and found myself transported home momentarily, looking at a painting by Marsden Hartley.

When you look at Mountain Lake—Autumn, you can almost feel the crisp breeze and smell the sun-warmed leaves and damp ground. It is a spectacular painting of a mountain and a lake, covered with the brightest trees in the middle of a magical autumn. So maybe this is reading more like a love letter to Maine, but if you’ve ever been to New England in the fall, after having just lived through a summer in a beyond-humid area, you know how invigorating it is and what a bath for your eyes this painting can be.

The blue that Hartley uses for the water and the yellow in the trees, to me, are spot on. On a clear day on a lake in inland Maine, you can see each of these colors—in the reflection of the sky on the water, in the vegetation that blankets the entire state, and in the leaves that turn when they get that first taste of cool air.

Marsden Hartley grew up in Maine, moved away, and once he declared himself an artist, he came back and painted. Hartley gave the painting to artist Rockwell Kent, and Kent gave it to museum founder Duncan Phillips. Upon receiving it, Phillips wrote to Kent and said: “The Hartley is so fine a picture that I hesitate to accept it but the reason you give is a good one namely that in our Gallery many people will enjoy it to the artist’s benefit and to our mutual satisfaction.”

I miss finding Mountain Lake—Autumn in the Phillips’s galleries, and stopping to drink it in, think of home, a perfect fall day, and that damp brisk air that smells like leaves. Most of all, though, I miss wandering through the galleries, seeing my coworkers, and smiling as they, too, find something to stop and enjoy for a brief moment in the workday.