We’ve partnered with STABLE arts, a studio complex in DC that provides visual artists with an active workspace. STABLE artists picked a permanent collection artwork and explain how it intersects with their own practice. Visit the Phillips Instagram for more STABLE artwork.

Read Part I

Read Part II

Ying Zhu (@Yoyoying)

The first time I stood inside the Laib Wax Room, the sense of being wrapped was overwhelming. Laib’s choice of bees wax as a material intertwines nature and man made, ephemeral and permanent. It transcends time, and led my mind wonder where past and future converge. The work I choose to share is a sprig of pine suspended in air, each needle wrapped with thread. As time passes, needles start to fall, effortlessly demonstrating grace, ephemeral fragility. It unwrapped the course of life/time passing. As an artist, utilizing natural material, and watching it change and take a life of its own path was a very powerful experience. It was a way of learning to acknowledge and accept.

Born and raised in China, Ying Zhu lives and works in DC, and is a proud STABLE artist!

(LEFT) Wolfgang Laib, Wax Room: Wohin bist Du gegangen – wohin gehst Du? (Where have you gone – where are you going?), 2013, Beeswax, light bulb The Laib Wax Room is supported by The Phillips Collection Dreier Fund for Acquisitions; gifts in memory of trustee Caroline Macomber; Brian Dailey and Paula Ballo Dailey; a community of online contributors; and a partial gift of the artist. Wax donated by Sperone Westwater, New York (RIGHT) Ying Zhu, No Strings Attached

Matt Storm (@mattstormphoto)

I was enthralled by Zilia Sánchez’s show at the Phillips in spring 2019. At the time, I was struggling to figure out how to create photographs that stretched across space and engaged the viewer’s body as an equal, and were photographs at their core. Sánchez’s stretched, sculpted canvas pieces were a revelation—clearly paintings, clearly in space, undeniably powerful. Anyone I talked to that spring heard about that show. My work now includes “in space” pieces that feature large-space fabric photographs installed around an armature, letting the work truly share space with the viewer. I’m inspired by how many years and media Sánchez’s career has spanned while retaining a singular, authentic, innovative, and witty voice.

Matt Storm is a photo-based artist in Washington, DC, creating work about identity, using visual topics including self-portraiture, transgender and queer issues, family, and community. He serves as Chair of the LGBTQ Caucus of the Society for Photographic Education, and is a 2020 recipient of the Arts & Humanities Fellowship from Washington DC’s Commission on the Arts & Humanities. Deeply involved in DC’s transgender community, Storm also engages in transgender-related curating projects. Screen reader support enabled.

(LEFT) Zilia Sánchez, Maquinista, diptico (Machinist, diptych), 2008, Acrylic on stretched canvas, 62 x 13 5/8 x 6 in, each., The Phillips Collection, Director’s Discretionary Fund, 2016 (RIGHT) Matt Storm, Act of Looking II, 05, Going for It – In Space

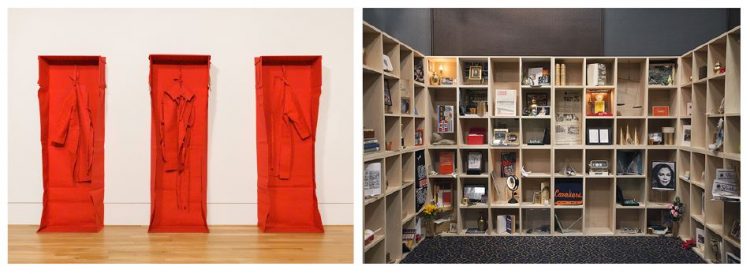

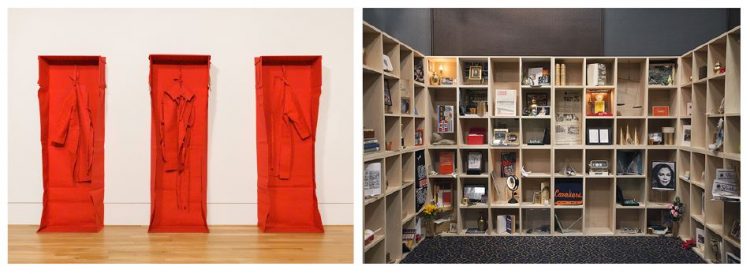

Leigh Davis (@leighdavisprojects)

It’s been 10 years since I visited (and revisited) Franz Erhard Walther’s Work as Action at Dia Beacon. His thinking/making/process turned me upside down in the best way. As a spectator you must take part in his work in order to complete the aesthetic experience. These works require not only reception but participation. His works are unique opportunities to be more open, to trust, and to be present with others (strangers alike). When I create installations or site-based works I think of what I felt through his work; sharing in the process of art rather than its product.

Leigh Davis is an interdisciplinary artist who explores the intersection of culture, community, memory, and place. Her work has featured at Open Source Gallery and BRIC (Brooklyn), EFA Project Space (NYC), Oliver Art Center at CCA (Oakland), and MICA (Baltimore). Her recent project Inquiry into the ELE (2016-19) sponsored by NYFA, was exhibited at Vox Populi (Philadelphia), Smith Center, and Transformer (both DC) and she teaches at Parsons School of Design (NY).

(LEFT) Franz Erhard Walther, Roter Gesang (Red Song), 1984, Cotton, wood, each sculpture: 90 1/2 x 29 1/2 x 11 7/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Arthur and Carol Goldberg, 2013 (RIGHT) Leigh Davis, Secular Columbarium for the Island, Participatory Installation, 2011 Capitol Skyline Hotel, DC

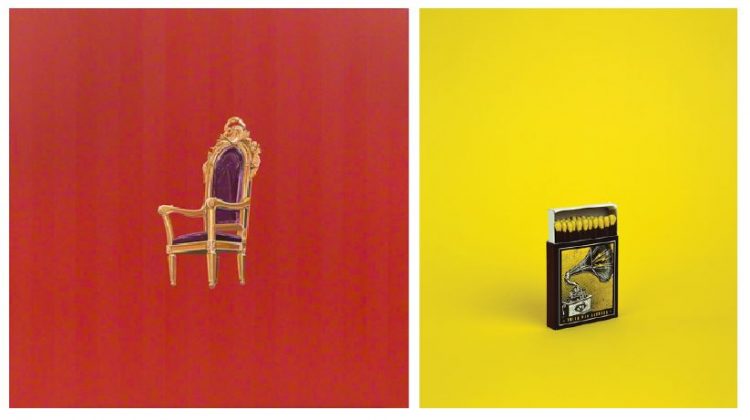

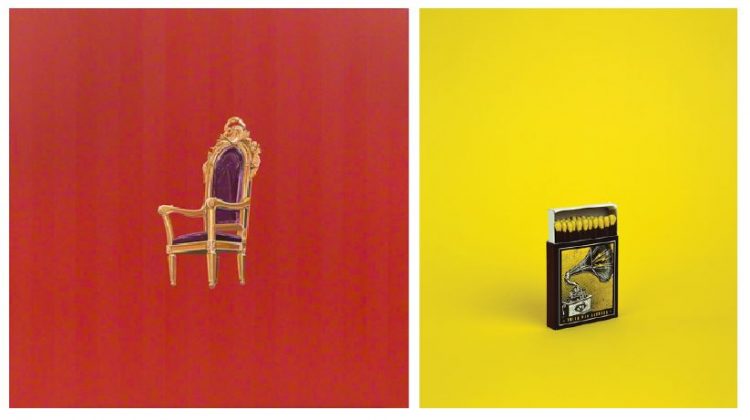

Nancy Daly (@nancydaly)

The work I selected that relates to Papal Thrown is from a photographic series called “American Miniature,” which I completed in 2019 with Kim Llerena after a series of cross-country road trips. The series reveals an affinity for the kitsch that comes along with exploring roadside America. Souvenirs from various sites are presented against brightly colored backdrops. Souvenirs present a strange dichotomy—they are inherently and inextricably linked to a place, but their value relies on them becoming divorced from that place and re-contextualized in an entirely new one. Robert’s painting clearly relates compositionally and in her use of color but I also see connections between the work in terms of divorcing a loaded object from its context in the world and the kind of disembodied nostalgia this creates in a piece.

Nancy’s current body of work examines how the development of the online social world is affecting identity and social behavior. Nancy Daly is a graduate of the Photographic and Electronic Media MFA program at the Maryland Institute College of Art. She lives and works in Washington, DC, where she maintains an active studio practice, exhibiting nationally while also working as the Program Director for Hamiltonian Artists.

(LEFT) Julie Roberts, Papal Throne, 1998, Oil on acrylic ground on cotton duck, 36 x 36 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of the Tony Podesta Collection, 2014 (RIGHT) Nancy Daly, Third Man Records, Detroit, MI (matches)

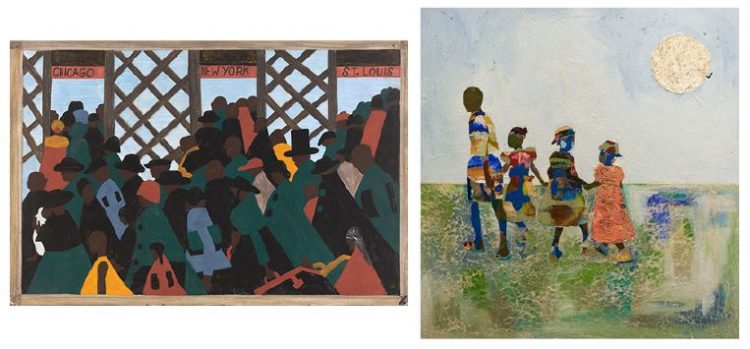

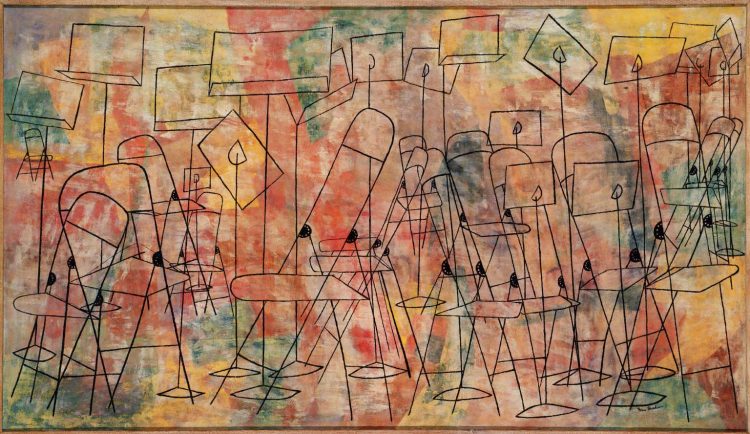

Charles Jean-Pierre (@cjpgallery)

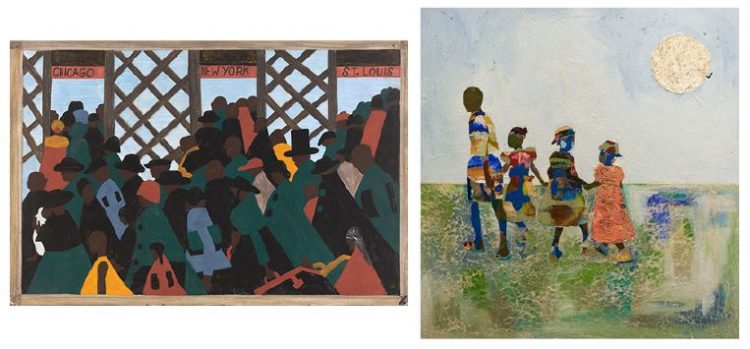

I was first introduced to Jacob Lawrence’s seminal work as a graduate student at Howard University. Later when I became an art teacher, The Phillips Collection became a vital resource for me to engage in discussions with my students about the mass movement of African Americans from rural southern towns to northern metropolises like DC, Baltimore, Chicago, and New York. Panel 1 resonates the most with me because it sets the stage for exploring the lasting cultural, political, and societal impact of my own migration story. Lawrence’s work inspired a series of my own entitled, “Future Memories: Exploring the Diasporic Imagination” to illustrate the rich tapestry of the contemporary Caribbean and Latin American migration experience.

The lines, spaces, and gaps in my work represent the absences felt growing up in an immigrant home. My practice recognizes the erasure of our complex histories and challenges the narrative that we are perpetual outsiders. My work attempts to create the informed cultural context needed to make sense of the American connection to the Caribbean, and vice versa.

(LEFT) Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 1: During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans.,1940-41, Casein tempera on hardboard, 12 x 18 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942 (RIGHT) Charles Jean-Pierre, The Autobiography of My Mother

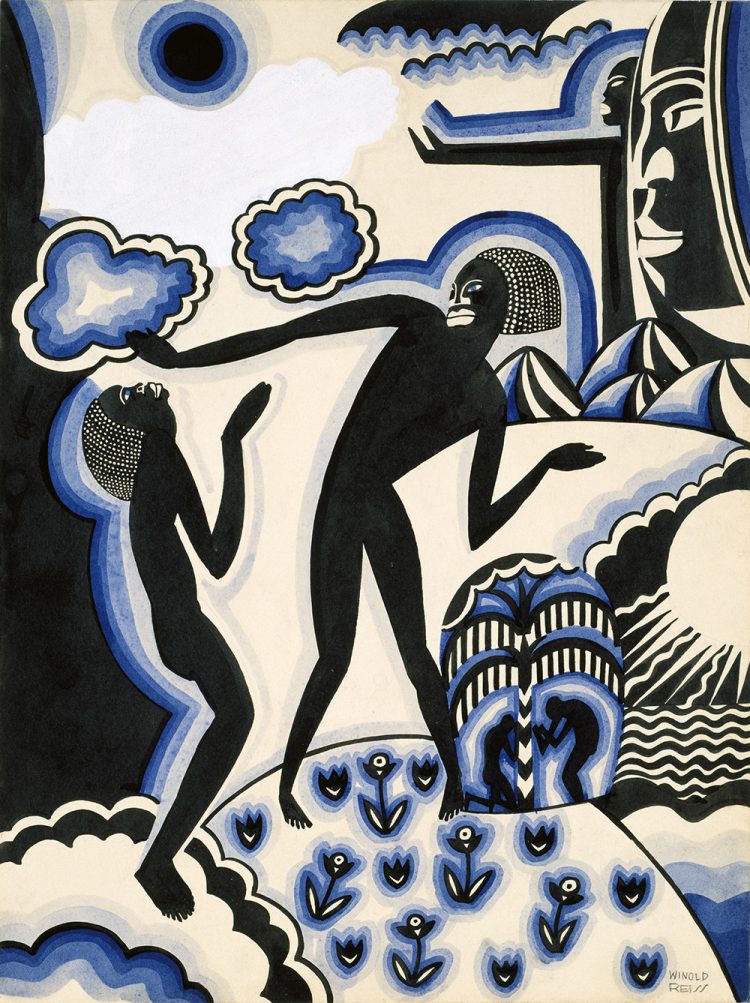

Aziza Claudia Gibson-Hunter (@gibsonhunterstudio)

I was a figurative artist until I hit a plateau. It was a place where the figure got in the way of my ideas. I had just had an exhibition titled Suspicious Activities, a series surrounding the war in Iraq in 2008. I had worked on Suspicious Activities for three years, absolutely compelled by my sense of fury surrounding the war in Iraq and the gentrification taking hold in my community. The figure began to betray me. I could not make it express the turmoil I was feeling. I felt that I was at some type of impasse. Mr Gilliam attended that exhibition. He asked me to return and review the exhibition with him, and he walked the exhibition with me asking questions, offering insights and encouraging words. He was nice enough to open his studio to me, share books, and discuss art with myself and other artists he took interest in. Over the years I have had the opportunity to watch his work progress, to see him continue to push himself to grow, and to observe his interactions with his staff. Mr. Gilliam is prolific, focused, and driven. To know him has been tremendously instructional.

Aziza Claudia Gibson-Hunter is a mixed media artist living in Washington, DC.

(LEFT) Sam Gilliam, Purple Antelope Space Squeeze, 1987, Diptych: Relief, etching, aquatint and collagraph on handmade paper with embossing, hand-painting and painted collage, 41 1/2 x 81 5/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Bequest of Marion F. and Norman W. Goldin, 2017 (RIGHT) Aziza Claudia Gibson-Hunter, Dawn

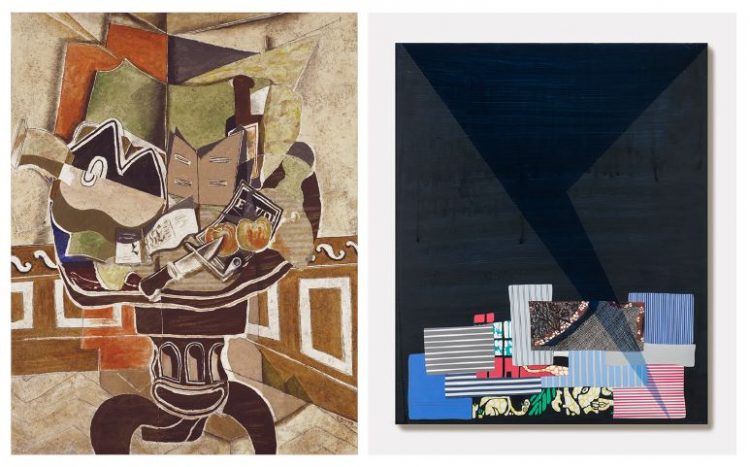

Tim Doud (@Tim.doud)

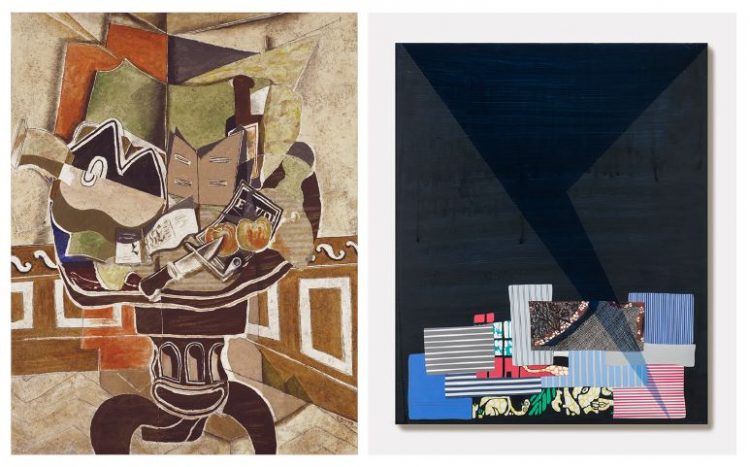

I’ve had an interest in George Braque since I was an undergrad. I like the use of flatness in his work and with a particular affinity for the way he flips the objects in space. It is unsettling. My work over the last few years has engaged collage—by making paintings of collaged images

Tim Doud is a multimedia artist with an emphasis on painting. He is the co-founder of STABLE in Washington, DC, and co-founder of the ‘sindikit project in Baltimore. Doud is a Professor at American University.

(LEFT) Georges Braque, The Round Table, 1929, Oil, sand and charcoal on canvas 57 3/8 x 44 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1934 (RIGHT) Tim Doud, CDGJWAT (Lt Blue) M