On Sunday, April 14, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo and the Shanghai String Quartet perform the world premiere of Therapy by composer Marcos Balter. Senior Director of Phillips Music Jeremy Ney sits down with Balter to explore the origins, inspirations, and compositional processes behind Therapy, co-commissioned by The Phillips Collection and Chamber Music America.

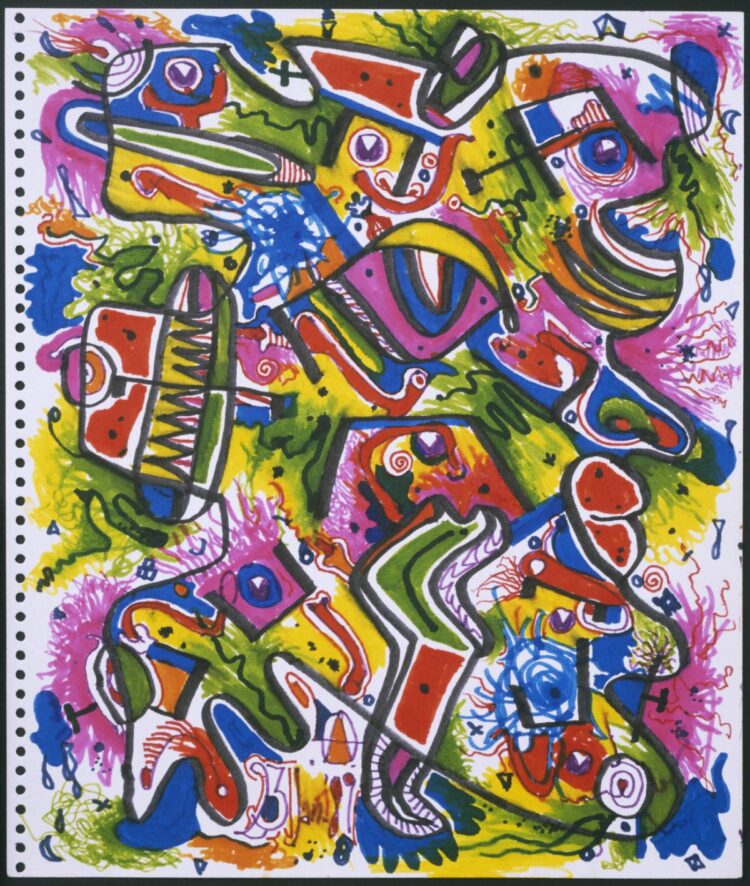

Following the effects of the global pandemic, Marcos Balter focused his new work—titled Therapy—on concepts of catharsis and the healing potential of creativity, with fragmented text drawn from Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. Balter chose Alfonso Ossorio’s Recovery Drawings from the Phillips’s permanent collection as inspiration. Ossorio sketched the 42 Recovery Drawings while in the hospital recovering from heart failure in the final years of his life. The wildly evocative set of drawings proves that physical restrictions need not constrain imagination, and that limitations can be both generative and transformative.

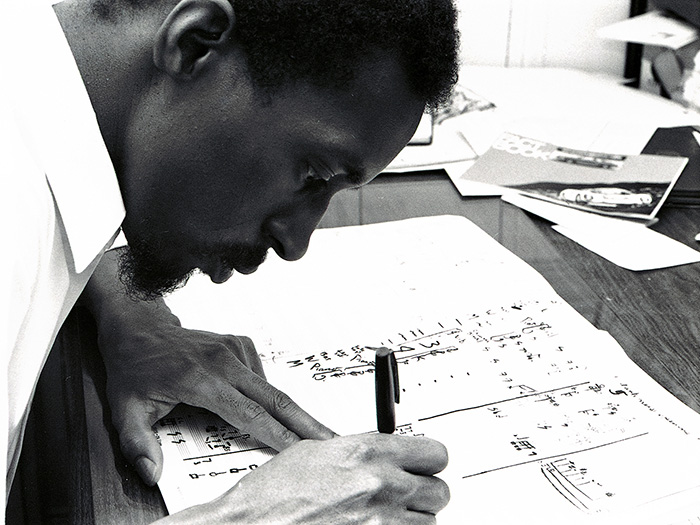

Marcos Balter

Q: Tell us about the origins of Therapy as a piece and your process in writing it. It was composed in 2021 but is only now receiving its world premiere in 2024. There seems to be a long arc in the journey of realizing this piece. How did it start and where did it take you?

A: The title says it all. I had a really hard time feeling inspired by anything during a global pandemic and amidst total sociopolitical chaos. That moment felt too complex and painful to be captured in real time. Trying to translate it to music felt opportunistic and reductive. I felt personally and artistically depleted. But then, after many false starts, it dawned on me that the only genuinely thing I had to share at that time was exactly that: my own attempt to remain well, to find my own path towards healing.

Q: As a composer you are frequently writing pieces for specific players in mind, players who often know your music intimately. In this case, what were the qualities in Anthony and the Shanghai Quartet’s musicianship and musicality that fed into your thinking and the compositional process for the piece?

A: The short answer is: everything. Knowing my collaborators both artistically and personally allows me to mentally hear them rather than their instruments. I’ve known Anthony for many years, and the members of the quartet and I taught at the same institution for six years. Anthony is as brilliant an actor as he is a singer. You never feel like he’s delivering a performance; he speaks to you. And you listen, but not as one listens to music: you listen as if you are having a private conversation with him. And the Shanghai Quartet folks know each other so well that even the most contrapuntal discourse feels like mere facets of a single voice that, while contracting and expanding, remains beautifully unified.

Q: Tell us about the interplay of the two forces here – countertenor and string quartet. Within the score, they seem to operate as distinct units, the string quartet has a texture governed by often very quiet dynamics and subtle timbral effects, and the countertenor seems to have an oratory or poetic role, with a greater freedom of melodic contour. How are these two forces interacting and contending with each other?

A: There’s a beautiful juxtaposition of stasis and kinesis in both Ossorio’s drawings and Stein’s text that transforms objects into subjects, patterns into feelings. The sheer materiality of things becomes their soul. I tried to capture that. That is to say I don’t hear it as voice accompanied by string quartet or two separate forces, but rather as spaces and objects that become animated by added meaning.

Q: In your wider music there’s been an interesting throughline of visual input or visual stimulus. Sometimes that’s specific paintings, such as the Cy Twombly work that inspired your piece for Claire Chase in 2012, Descent from Parnassus. In other cases, you’ve explored ideas from graphic design and typology (Kerning), visually dramatic projects like Pan, and more recent pieces exploring color (Livro das Cores – Book of Colors) and ideas drawn from the parallel acts of looking and listening (Vision Mantra). In this piece the visual input is Alfonso Ossorio’s Recovery Drawings from the Phillips’s permanent collection. Tell us about your choice of Ossorio’s work and how the Recovery Drawings inform Therapy.

A: Ossorio’s Recovery Drawings were his therapeutic diary while convalescing in a hospital during his last two years. Crafted solely with felt-tip watercolor markers and crayons on sketchbook paper (evident from the spiral coil holes along the edges in some pieces), they are as exuberant as they are vulnerable. There’s a sort of molecular quality to them, where the sum of many shapes and colors coalesce into supernatural beings. Yet, this fusion feels more tethered than symbiotic, like a deliberately botched and painful birth. They are violent yet fragile, precarious. Through them, I finally found a way to animate my own fear of isolation and mortality, a path to give my inner monsters a face. The immediacy of visual stimuli is something I always strive to capture in my music, and one of the reasons for my love for the visual arts.

Alfonso Ossorio, Recovery Drawings #2, Book 1, 1989, Felt tip pen on paper, The Phillips Collection, Gift of the Ossorio Foundation, 2008

Q: People often discuss the concept of hybridity in your work, which in one sense captures a certain stylistic predisposition towards synthesis, of framing (musically) different ideas drawn from the mythological, visual, or literary topos. This is essentially the conceptual domain. However, when you are composing, with the tools and means of music and its systems of notation, melody, harmony, rhythm, and dynamics, how do you continue to think about visual ideas? The two forms are complimentary in many ways but not necessarily translatable. How do you bridge the divide between the two domains?

A: It’s a battle. The conventional view of music as a disembodied phenomenon doesn’t appeal to me. The emphasis on Cartesian dualism, separating mind and body, permeates most compositional tools, from notation systems to structural approaches to harmony. Yet, as a composer, I do value intentionality, which is often more easily achieved through systematic methods. And then there’s the almost fetishization of sound, or, as Cage once said, letting “sounds be sounds,” which seems absurd to me. No sound is just a sound unless we choose to erase its source, which is quite a problematic posture in my view. Bringing techniques and perspectives from other art forms allows me to escape this facelessness of music-making. It connects me to materials, bodies, words, and images in ways that are more substantial and structural rather than merely programmatic.

Q: Tell us about your engagement with the Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. Where did this inspiration come from for the text within Therapy?

A: This is my second foray into “Tender Buttons.” Over a decade ago, I composed a piece for the bassoonist Rebekah Heller titled “…and also a fountain,” which are the final words of Stein’s book. I focused the entirety of that piece on the book’s last paragraph, which left me yearning for another opportunity to explore other sections. Once I discovered Ossorio’s drawings, my mind immediately turned back to the book.

Q: The text is quite fragmentary and spliced together almost as a compositional tool itself that is ‘extra-musical’ in a sense. How does this collage-like approach to textual abstraction help create a sense of arc (be it narrative, musical, or both) in the piece?

A: Stein’s “linear non-linearity” is rather similar to the way I think of my own music. I find myself particularly drawn to writers who approach their craft in a similar manner, such as Clarice Lispector, for instance. While there are recurring themes in their work, they are rarely presented in a hierarchical fashion. Instead, there’s a sense of unity that pervades the text at any given point. This provides me with the freedom to extract phrases, or even fragments of phrases, and weave them into new shapes that align with my musical instincts. There’s an implicit invitation to manipulate it that is quite generous and seductive.

Funding for this commission was generously provided by the Sachiko Kuno Philanthropic Fund.

Funding for the performance was generously provided by an anonymous donation.