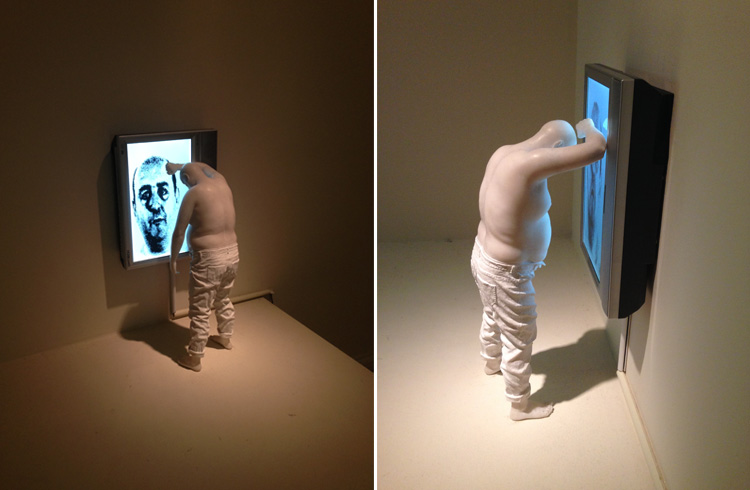

Bernardi Roig, Insults to the Public, 2007. Polyester resin, marble dust, and TV/Video monitor. 22 4/5 x 8 1/4 x 9 in. Private Collection. Photos: Annie Dolan

In just a few days we say goodbye to Bernardi Roig’s six sculptures that have truly become a part of the Phillips’s landscape over the past five months. A lengthy exhibition time is fitting given the inconspicuous nature of the works, placed in unsuspecting spaces throughout the galleries. For frequent visitors to the museum, it might have taken a couple of walkthroughs to find all six. That was precisely Roig’s aim: to activate areas of the museum typically not used for exhibition space.

The smallest of the sculptures, Insults to the Public (2007) is the most inconspicuous of all, hidden in an elevator bank on the second floor of the original Phillips house. Although the smallest in size, Insults to the Public is the only one with an audio component coming from the small LCD screen featuring a speaking portrait. The colorless, faceless plaster sculpture is therefore not only illuminated by the vibrant lights coming from the screen, but also brought to life by the moving image which seems to be lecturing the weary figure leaning against it. With distorted bodily proportions and suggestive body language, Roig’s miniature standing figure evokes a feeling of simultaneous exhaustion, shame, and defeat.

My interpretation of this work is that the man on the screen could easily be the face of the sculpture himself. With a hanging head and a faceless expression, the man has no identity, yet his bald head matches the bald head on the screen in front of him. Is the speaking man giving his own tired body a critical lecture? This added dimension makes Insults to the Public one of the most thought provoking of the six sculptures given the suggestion of self-inspection.

We might have to say “goodbye” for now to Bernardi Roig’s sculptures, but we’ll always look at the spaces they inhabited with a new level of appreciation, remembering these haunting sculptures.

Annie Dolan, Marketing and Communications Intern