This article, written by collector Anita Reiner’s daughter, Renee Reiner, was first published by Christie’s in May 2014 and is reposted here in three parts in conjunction with the exhibition A Tribute To Anita Reiner, on view at the Phillips through Jan. 4, 2015. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here. We welcome others to share their own anecdotes about this legendary collector or contribute comments about the installation honoring her.

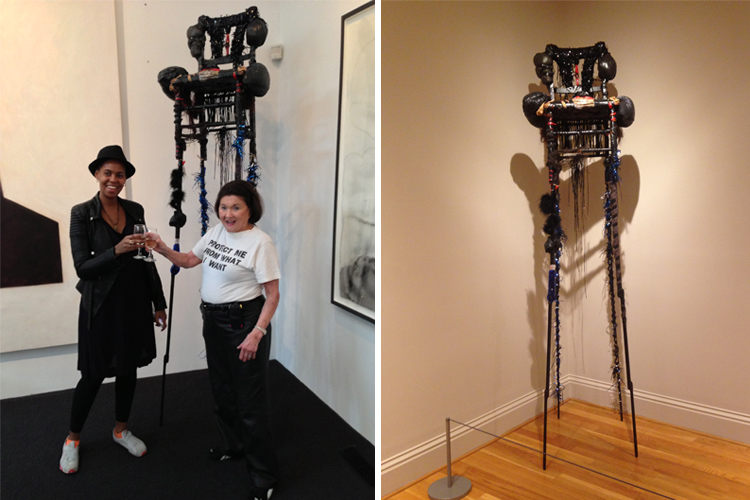

(left) Wangechi Mutu with Anita Reiner (right) Installation shot of Wangechi Mutu’s work at the Phillips

In 1971, we moved to a new house, built by our dad. It was designed with Anita’s passion in mind, allowing her to showcase her growing collection: It featured white walls, high ceilings, bright light. With this new space, Anita was off to the galleries at an ever-increasing pace. As her skill and knowledge developed, she became even more focused. The contemporary art world drew her in; there was a deep respect growing between her and her gallery-owner colleagues. Relationships with Leo Castelli, Ivan Karp, Anina Nosei, Arnie Glimcher, Jack Shainman, Mary Boone and others became long-lasting friendships.

With her passion came a vibrancy and sense of purpose. Our mom was never more alive and engaged than when a new piece of art was delivered to the house. In truth, her drive had more than an intensity to it; Mom had a fun-loving, impish side as well. Collecting art for her became integral to her sense of self and she had a lot of fun pursuing this passion. Her life philosophy, according to friend Wendy, was summed up in the words on two of her favorite t-shirts: “I am a conceptual work of art.” and “I am not boring!” She was, says Wendy, truly one of a kind.

We, her family, came to respect mom’s keen eye and visual acuity. Professionals in the art world respected this as well, seeking out her thoughts and her opinions. She was immersed in art and artists, primarily in New York, but also in other cities in the US and around the world. She and dad were regulars at the Basel Art Fair in Switzerland, the Venice Biennale, Documenta and Miami Basel. They loved to explore new places and Anita would always seek out the edgy, controversial, or revolutionary artists of the places they visited, whether it was in China, India, Burma, Fiji, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Germany, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, London, or France. No matter the location, she would walk into a gallery exhibit, see a dozen pieces of art, and, within a minute or two, would gravitate to the most compelling piece in the show and say, “put it on reserve.” Then she’d sleep on it. If the piece was still with her in the morning, she knew she had to buy it. She rarely had regrets over her spontaneity; however, she was on occasion sorry when she left a piece behind.

Around 2000, Anita had our dad build a new room on the house: she needed more space for her growing collection. Always thinking about art, but not necessarily offering all pertinent information up front, Mom had purchased a set of oversized Jorgé Pardo doors (her friend Steve Shane remarked that they looked like sperm). The opening to this new room needed to be designed and built to accommodate them. We wondered at the time if Dad knew she’d been counting on a new room all along.

Anita rarely sold pieces from her collection. If she fell out of love with a work, it was because her taste was growing and shifting, or because she needed space for something new. She always had her finger directly on the pulse of what was good, valuable, important. It was obvious that her family members were not the only ones impressed with her skill and vast knowledge; plenty of folks in the contemporary art world in the US and abroad enjoyed her expertise and her company and she had long lasting friendships with fellow art aficionados from around the world.

Renee Reiner