In this series, Phillips Manager, Archives and Library Resources Juli Folk and Digital Assets Librarian Rachel Jacobson explain the ins and outs of how archives work.

Welcome to another installment of Archives 101. So far, we have reviewed what an archival collection is and critical steps in archival processing. Now, let’s focus on describing archival material so that you, the researcher, might decide whether or not to seek further access to an archival collection.

The primary tool to figuring out whether or not an archival collection may be of use to you is the Finding Aid. A finding aid, according to the Society of American Archivists, is a description that typically consists of contextual and structural information about an archival resource. A finding aid should place the archival resources within context that allows a user to decide if they want to explore a collection more thoroughly. The contextual information generally included in a finding aid is:

- • Title for the collection

- • Dates, including bulk dates which indicate the period that most of the material is from

- • Note about what can be found within the collection, usually called a scope and content note

- • Provenance information

- • Note about how the material has been arranged, usually called an arrangement note

- • Description of the formats within a collection and storage information

As was the case with accessioning and arrangement, there is some wiggle room around how finding aids are written. However, this should not indicate that there aren’t documented standards and procedures for an archivist to follow.

The Phillips Collection archival repository is embarking on a new era with the implementation of the archival information management system ArchivesSpace. One of the many helpful things about the management system is that it helps create consistency across finding aids due to format and required fields. It also is the first time our archival material will be in one centralized and searchable database. We’re making progress; getting all our archival holdings into the system is a lofty goal and will take time!

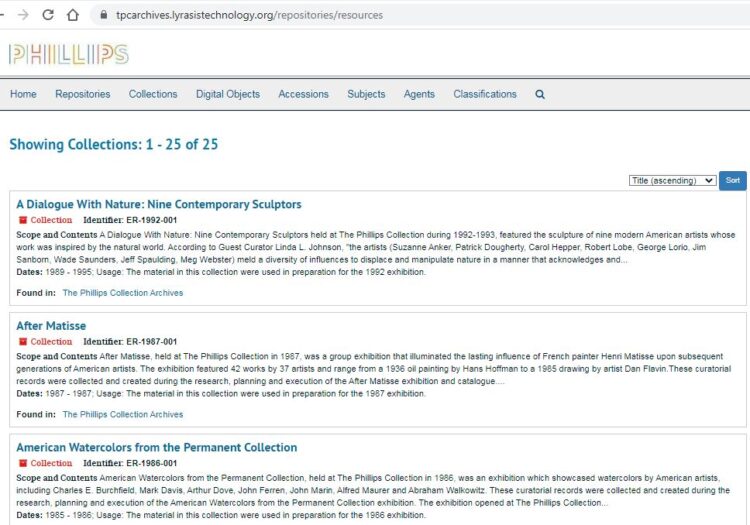

However, the system will make searching through finding aids much easier. Below is a screenshot of some of the archival finding aids in our instance of ArchivesSpace thus far. ArchivesSpace refers to finding aids as collections, which are what the finding aid guides you through.

Peek into our instance of the archival information management system, ArchivesSpace.

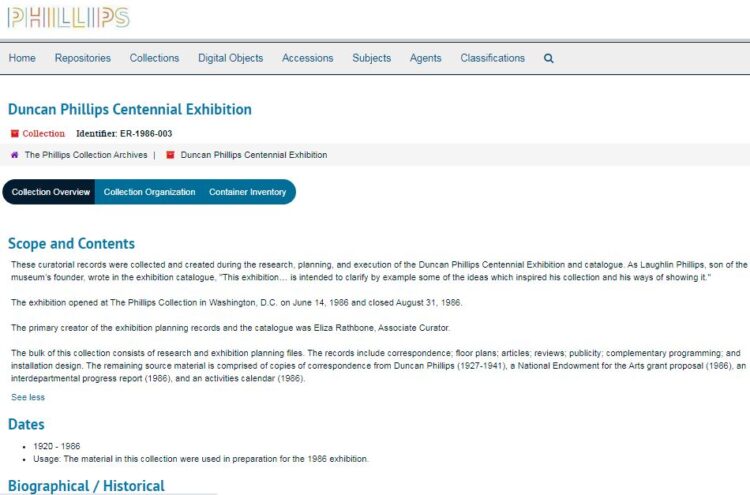

After reading the notes and other information that gives you insight into generally what exists within a collection you can take a closer look at the contents.

Take a closer look into the finding aid. Scope and contents notes, dates, and other information give you insight into what you can broadly expect to find from a given archival collection.

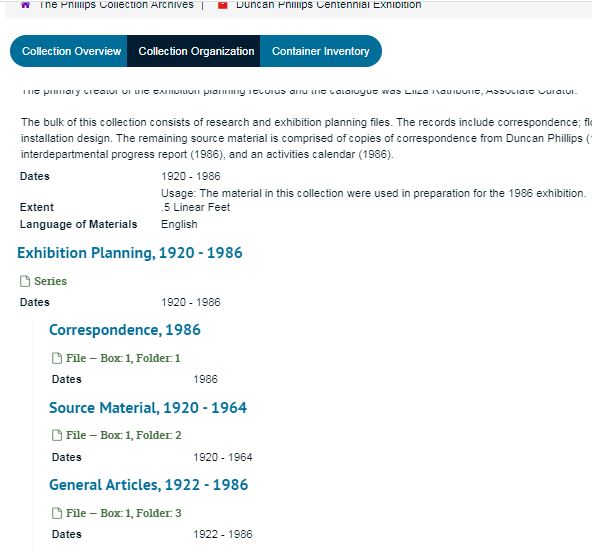

By clicking on the “Collection Organization” tab you can see more specifically what the contents of a given collection are. For example, you will find titles of folders and the dates for which the material was created.

If everything still seems relevant to your research inquiry it may be time to request access to a specific folder, set of folders, or archival box.

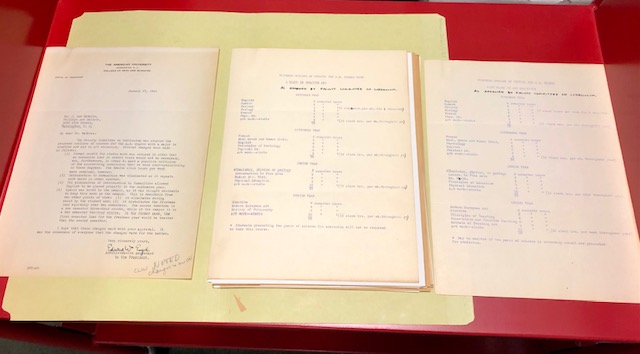

A look inside one of the folders from the papers of C. Law Watkins (associate director of the gallery and director of the art school). Some of our folders will be accessible remotely, but for most of the material, researchers will still need to look at them in person.

Due to the arduous nature of getting to the point where an archivist is ready to create a finding aid, The Phillips Collection Library and Archives does not yet have nearly all our archival collections described. We are working to catch up with our material. The more we have available to users, the more likely we are to find those diamonds in the rough. Stay tuned for more information about the launch of our ArchivesSpace repository this summer!