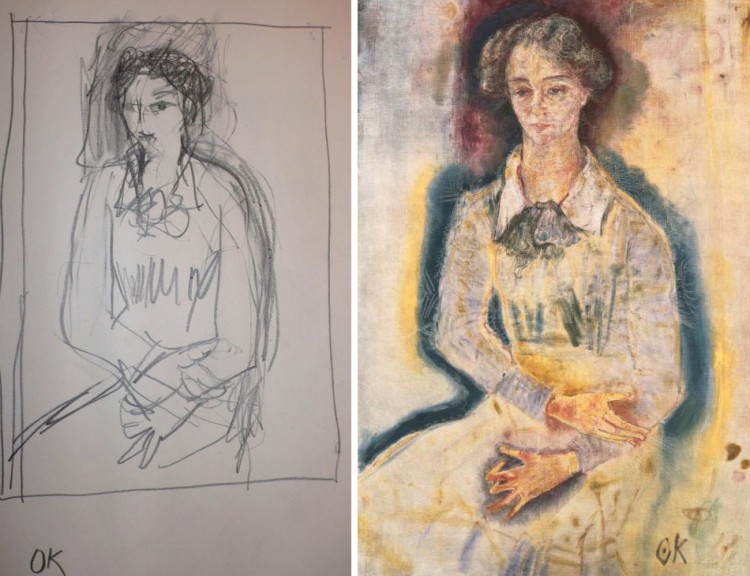

Oskar Kokoschka, Portrait of Lotte Franzos, 1909. Oil on canvas, 45 1/4 x 31 1/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1941.

When Lotte Franzos came to see her portrait by Oskar Kokoschka, the artist said “ Your portrait shocked you; I saw that. Do you think the human being stops at the neck in the effect it has on me? . . . ”

Do you want to know more about what motivated Kokoschka to paint Lotte Franzos the way he did?

A compelling and perceptive view on just that question is in a new book by Eric Kandel, Nobel Prize-winning neuroscientist, titled The Age of Insight : The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present.

The Age of Insight book cover

Kandel views art through multiple, powerful lenses: turn-of-the-century Vienna’s cultural mores and psychological insights. Looking back to the early 20th century, Kandel cites the proximity of the Vienna Medical Museum, the Sigmund Freud Museum (in Freud’s former apartment), and the Upper Belvedere museum, which houses a renowned collection of paintings by Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and Egon Schiele. The Vienna School of Medicine in 1900 led the way to discovering what was beneath the surface of the body just as Freud probed the unconscious. These scientific and psychological explorations were reflected in art. Kandel’s argument absorbs even later discoveries in cognitive science. He writes, “In art, as in science . . . reductionism does not trivialize our perception—of color, light, and perspective—but allows us to see each of these components in a new way.”

Lisa Leinberger, Volunteer Coordinator