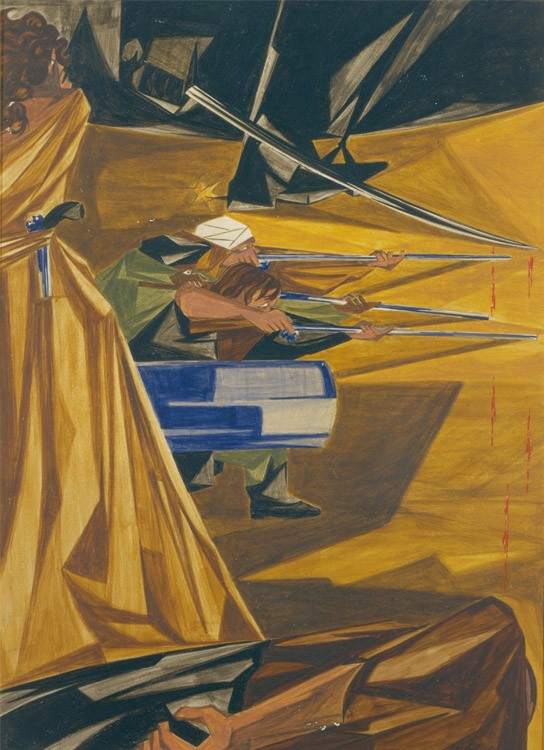

Jacob Lawrence, Struggle … From the History of the American People, no. 12: And a Woman Mans a Cannon (Molly Corbin, Defense of Ft. Washington, North Manhattan Island, November 16, 1776), 1955. Egg tempera on hardboard, 16 x 12 in. Private Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This spring, former Phillips curator Beth Turner taught an undergraduate practicum at the University of Virginia focusing on Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle series. In this multi-part blog series, responses from Turner’s students in reference to individual works from the series will be posted each week.

Panel 12 of the Struggle series tells the story of Margaret Cochran Corbin, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and the first woman to receive a military pension. Corbin originally served as a cook and laundress for the militia, but soon joined the battle as a matross, or cannon operator. When her husband’s matross partner was killed in action, Corbin took up the task herself. As the fight wore on, Corbin’s husband was also killed and she was left to operate the cannons alone. Although she was inexperienced in combat, Corbin was described as having excellent aim, a fact that the British did not overlook. With multiple British troops firing at her, Corbin held her ground and was the last cannon to stop firing in battle.

Though the entire piece details the narrative of Margaret Cochran Corbin, she is rather obscured in the panel. Filling almost the entire left side of the painting, Corbin’s dress is the same tan brown with abstracted shadows as the background and appears to blend in almost seamlessly. She is shown with her back to the viewer, focusing on the cannon fire. Additionally, the two accompanying figures appear much more dynamic. Lawrence is not allowing the viewer to see the most important part of the narrative. Instead, he provides insight through the text. In a removed, objective tone Lawrence reveals what is hidden in the panel’s abstraction, creating a relationship between the text and image that gives both new meaning.

Madeline Bartel