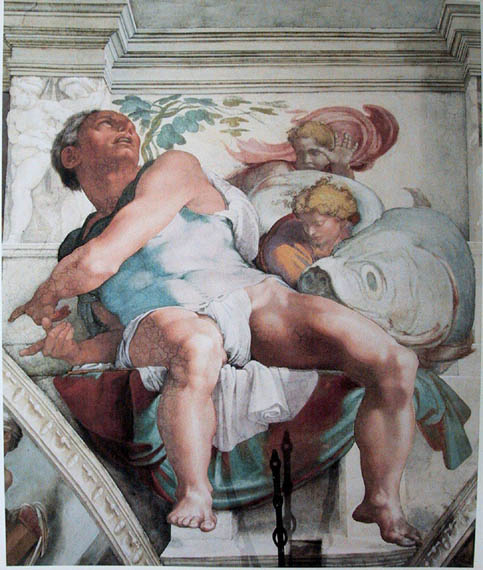

Experiment Station readers may recall my recent post on Philip Guston in relation to Bob Dylan. Washington City Paper‘s subsequent pairing of that piece with another post on Guston by my colleague Brooke prompted me to consider a term from the Italian Renaissance, Difficulta. This expression referred to a practice of artists of the period to depict a scene of self-conscious complexity, so as to show the artist’s mastery of their craft. The example most often described in art history is Michelangelo’s portrayal on the Sistine Ceiling of the prophet Jonah moments after he has been disgorged by the whale. The representation of these awkward, writhing figures so that they would appear gracefully and beautifully rendered was a way of visually boasting and showing one’s artistic prowess.

What does this have to do with Guston’s art, particularly the Phillips’s current exhibition Roma? Well in short, Guston’s art is a 20th century version of difficulta, where the artist sets up deliberate challenges that he strove to overcome.

Look at Guston’s art in Roma. The predominant color is a shade of pepto-bismol pink, very similar to the color of my third grader’s bedroom. More so than even today, during Guston’s time pink was associated with little girls. This pink is often painted alongside, blacks and grays, the archetypal adult colors of urban sophistication. As if to increase the tension, Guston also added the brightest reds, so that the any soft or neutral colors would be contrasted by a bloody cadmium. His brush strokes are thick, raw, and indelicate, yet they never appear careless or carefree. The brushwork is labored and worked over, as if the artist is struggling to achieve cohesion and solidity with the viscous texture of paint.

Philip Guston. Untitled, 1971. Oil on paper mounted on canvas. Private Collection, Woodstock, NY. © Estate of Philip Guston; image courtesy McKee Gallery, New York, NY

This exhibition features the output of a year in Rome, the Eternal city. An ancient world of ruins, monuments, blocks of stones and manicured trees that had inspired artists for centuries, but which Guston represented with a cartoon-like style that he said was inspired from comic strips like Krazy Kat. The Roman cityscape with its timeless components was often filled with images derived from Guston’s subconscious, Klansman’s hoods, heaping piles of shoes, hirsute legs bent awkwardly at the knees, stubby hands holding smoldering cigars, light bulbs in empty spaces. These images were symbols, alternately and sometimes simultaneously interpreted as references to the artist’s personal life and as having resonance in the popular imagination. For example, the piles of shoes that appear in his work were linked to the failure of his father, a junk dealer who committed suicide and was first found by Guston as a teenager; however the discarded mounds also conjured up photographs found at concentration camps, where the Nazis stockpiled the belongings of those sent to gas chambers.

Guston said that he felt compelled to express the tragic. This is perhaps the ultimate difficulta, especially when he did it by using artistic means, which seemed contradictory and intentionally made the goal of communicating meaning even harder. However, this must be seen as part of what motivated him, for if Guston wanted to show the tragic with a sense of difficulta, he certainly deviated from the Renaissance model in one very clear way. He did not want to make it look effortless but as a struggle. This does not make it an art easy to understand or enjoy, but one that expresses a compelling vision.

Paul Ruther, Manager of Teacher Programs