Ariana Kaye, The Phillips Collection Sherman Fairchild Fellow 2020-2021, on John Edmonds

On December 15, I had the pleasure of hearing artist John Edmonds talk about his work. In conversation with Dr. Ashley James, the two discussed how Edmonds’s work aims to show how Black people style themselves (or “self-fashion”) and his connection to both African art and to historically white and European art.

Tête d’Homme (2018) (at the Whitney Museum of American Art) and Hood II (2016) (gifted to The Phillips Collection in 2018) exemplify some of the key points that Edmonds talked about during the conversation. Both of these works are photographs. Edmonds emphasized the role that photography has had and still has in authentically or inauthentically portraying Black subjects. In the 19th century and earlier, photography was used to exploit Black people and present them as “others.” In Edmonds’s work, he seeks to reclaim objectifying photography and portrays Black subjects in empowering and true representations.

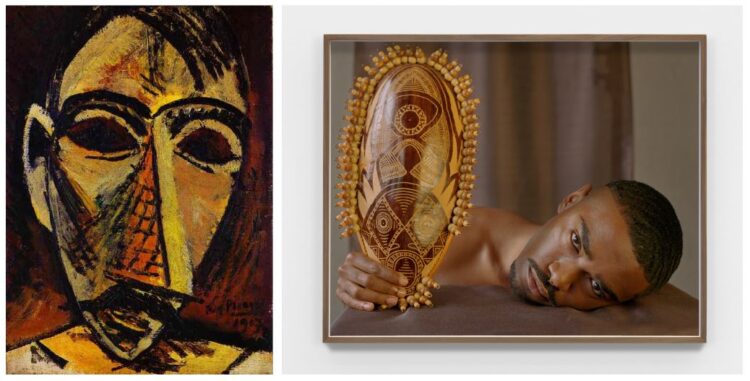

LEFT: Pablo Picasso, Tête d’Homme, 1907, Oil on canvas, Merion, Lincoln University, Barnes Foundation; RIGHT: John Edmonds, Tête d’Homme, 2018, Archival pigment photograph, 24 × 30 in., Courtesy of the artist and Company, New York

The French Tête d’Homme, translated to English as “Head of a Man,” references the types of titles that European artists like Picasso would use to title their works, most often inspired by African masks that they collected. By using the title, Edmonds seeks to reclaim the French and art historical linguistic use of the title, and show a head of a real man who is Black, with a work of art that connects him to his own ancestral past, in order to tell his own story about what the object he is presented with means to him.

Edmonds also collects African masks and figurines in order to investigate where they come from and which African tribe they could possibly belong to. He usually purchases the objects from different street vendors in New York City. He is not worried about the “authenticity” of the objects, but more about what they represent, that they have all been loved by generations of families and ancestors who appreciated them and used them for different aesthetic and ceremonial purposes.

John Edmonds, Untitled (Hood 2), 2016, Archival pigment print, 20 x 14 in., The Phillips Collection, Promised gift of Vittorio Gallo, 2018

While masks were used as forms of adornment in earlier centuries, according to Edmonds the new form of that is the hood, the sweatshirt, or the du-rag serving as a mode of self–fashioning for Black people today. The hood is seen in Hood II, from a series of photographs he started in 2016. We cannot see the face or gender of the person, also representing the universality of the hood—it does not have a gender. Many of Edmonds’s subjects are gender non-conforming individuals, and he believes that creating a society in which these people can live their truth is essential to being modern.

Dr. James exemplified John Edmonds’s work perfectly during the talk with her remark: “Let’s bring the Black body that caused all the conversation back into the conversation.” In Edmonds’s work, the Black body is the center of the conversation, reclaiming the Black past, present and future.

What is your vision for future Black representation?

To hear more from John Edmonds, listen to his Conversations with Artists event at the Phillips in 2019: