The Phillips Collection Fellow Arianna Adade on how the women artists featured in African Modernism in America, 1947-67 (on view through January 7, 2024) challenged depictions of womanhood.

Afi Ekong, Olumo Rock, 1960, Oil on canvas, and Manyolo Estella Betty, Cattle People, 1961, Acrylic on canvas

The depiction of African women in art has continually been valuable as well as fascinating. Throughout history, African art has captured the essence of women in a variety of mediums and environments in a way that the Western art world has often neglected. As more women started to become recognized as artists, the depiction of womanhood transformed through the progression of the modern art movements. These representations, whether traditional or modern, illustrate women in a multitude of positions, from nurturing mothers and wives to fierce warriors, leading the fight against Western colonization. Through art, women have illuminated a modern form of feminism that moves beyond the narrow Western narrative of womanhood. Instead, it investigates the fundamental functions women play in societal aspects such as politics, race, religion, and more.

The exhibition African Modernism in America, 1947-67 features nine women: Miranda Burney-Nicol, Ndidi Dike, Afi Ekong, Manyolo Estella Betty, Ladi Kwali, Grace Salome Kwami, Suzanna Ogunjami, Etso Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu, and Viola Mariethia Wood. Each woman has made vital contributions to African modern art.

Women expanded the subjects in art. With more representation of African women artists, they pushed past the matriarchal depictions of women to highlight the diverse contributions they hold in African societies and the messages they tell with it.

One example of this is Miranda Burney-Nicol’s The Conquering Hero. Carved into a Quaric writing board, the art portrays the horse and rider motif, visual iconography recognized in both African and Western traditions. She brings forth the connection of the past and present through wood carving, a traditional art form prevalent in Africa. As a symbol of the West African empires that once flourished before colonization, the horse is seen as a status of the wealth and power in the region’s history. Burney-Nicol’s use of the prayer board as a medium also shows the importance of religion in certain tribes and cultures.

Miranda Burney-Nicol (Olayinka) (1927-1996, Sierra Leone), The Conquering Hero, 1972, Incised Muslim prayer board, 21 x 9 x 3/4 in., Collection of The Newark Museum of Art, The Simon Ottenberg Collection, gift to The Newark Museum of Art, 2020, 2020.4.4

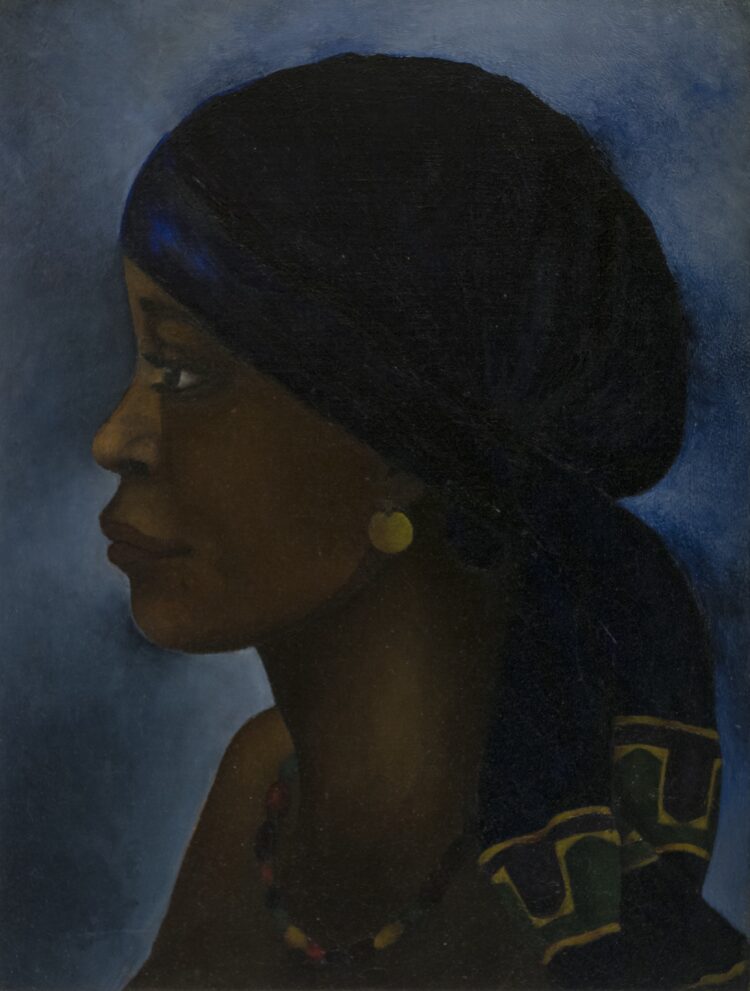

Even though portraiture was a widely explored expression of art in the Western world, African women artists specializing in portraiture used this art style as a way to capture the life and identity of the seemingly ordinary African woman. The historical components are interlaced with the fashion and beauty of their time. African modernist artists used portraiture as a way to connect and convey the cultural, social, and political stories of the continent that were typically ignored in the art world.

Suzanna Ogunjami’s A Nupe Princess depicts an older woman who is a royal member of the Nupe kingdom, an ethnic group in central Nigeria. Wearing a red, green, and black necklace, the woman illustrates the colors of pan-Africanism. This not only acts as a reflection of her Igbo-Jamaican identity but also as Ogunjami’s efforts to preserve West African artistic traditions.

Suzanna Ogunjami (c. 1885-1952, Igbo), A Nupe Princess, 1934, Oil on canvas; Framed: 21 1/2 x 17 1/2 x 2 1/8 in.; Fisk University Galleries, Fisk University, Nashville, TN, Gift of the Harmon Foundation

Grace Salome Kwami’s A Girl in Red (Portrait of Gladys Ankora) is also an exploration of portraiture in modern African art. Gladys Ankora, a woman who worked in Kwami’s sister’s household, serves as a representation of Ghanaian women and identity in art. With no African art history courses being taught in Ghana to rely on, Kwami produced her own idea of realism. Although seemingly simple, Kwami produces a warm red and brown palette paired with patterned clothing and a headscarf—often referred to as “kente” depending on the fabric and pattern; clothing is seen as an integral part of individual expression in Ghana. Subtly woven into her subject, Kwami showcases delicate touches of gold jewelry, highlighting a significant aspect of the country’s rich history, known for its abundance of gold.

Grace Salome Kwami (1923-2006, Ghana), A Girl in Red (Portrait of Gladys Ankora), 1954, Oil on linen on canvas, 29 15/16 x 22 in., Courtesy of Atta and Pamela Kwami

Today, as the fight for women’s voices continues to expand, artists use their practice as a way to challenge gender-based oppression. The systemic barriers that women have faced that have limited their artistic expression are prevalent when looking through the history of art; however, the strides women have made continue to flourish, opening doors for the voices and sociopolitical issues to be amplified.

Ndidi Dike’s collage-based work The Politics of Selection delves into the intricate relationships between identity and politics. By incorporating women of the Diaspora who contributed to African modernism in art, she exposes the marginalization and silencing of women throughout history. She particularly focuses on archives of Nigerian artists such as Afi Ekong, Etso Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu, and Ladi Kwali. In her muted-color collages, she depicts women artists being physically overshadowed and concealed by their male counterparts. The mixed media collection serves as artistic documentation of the absence of women in the arts—particularly Black women—and the political elements surrounding the issue.

Ndidi Dike (b. United Kingdom; active Nigeria), The Politics of Selection, 2022, Photocollage printed on transparency, earthenware vessel, earth, book, paper, 48 1/8 x 72 1/2 in., Courtesy of the artist