Museum Assistant Celine Krempp, during her detail in the Library and Archives, explored the relationships between the Impressionists via art critic Thadeus Natanson’s book.

There is a lot about the Impressionists that we already know. We know the time period during which they worked. We know their styles, their inspirations, and their legacies, etc. We also know that the Impressionists knew one another. But one question is, how much do we know about the Impressionists’ relationships with one another?

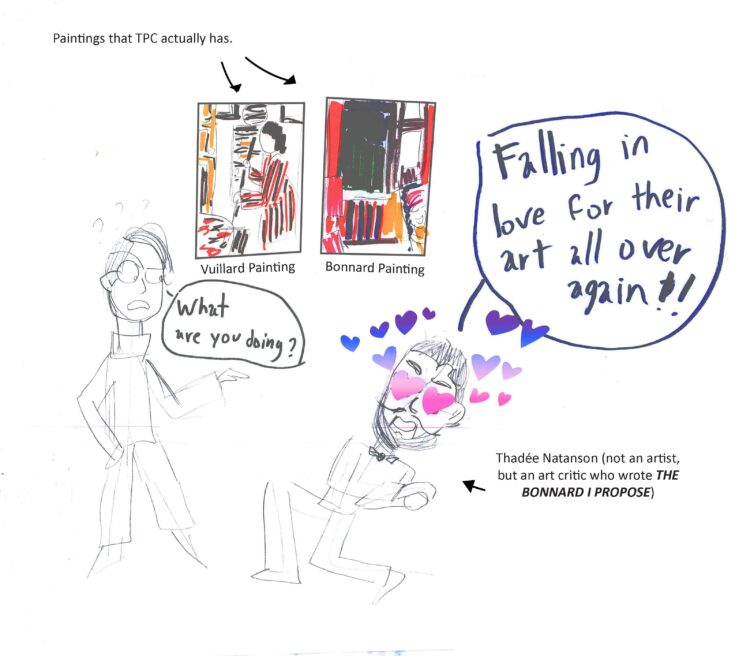

While participating in the Museum Assistant Detail program at The Phillips Collection’s Library & Archives, one of my tasks is translating texts from French to English for the Bonnard’s Worlds exhibition (opening March 2). Another task is to reorganize the bookshelves. As I shelved books related to Bonnard, I stumbled upon a book written by Thadeus Natanson. The name rang a bell because I remembered it from a Bonnard article I translated earlier. Natanson published this book, The Bonnard I Propose, on June 1, 1951, a couple months before his death. Thadeus Natanson was a Polish-born French art critic and collector, and Bonnard was one of the many artists he worked with. I didn’t have to translate this specific book, but how could I resist?

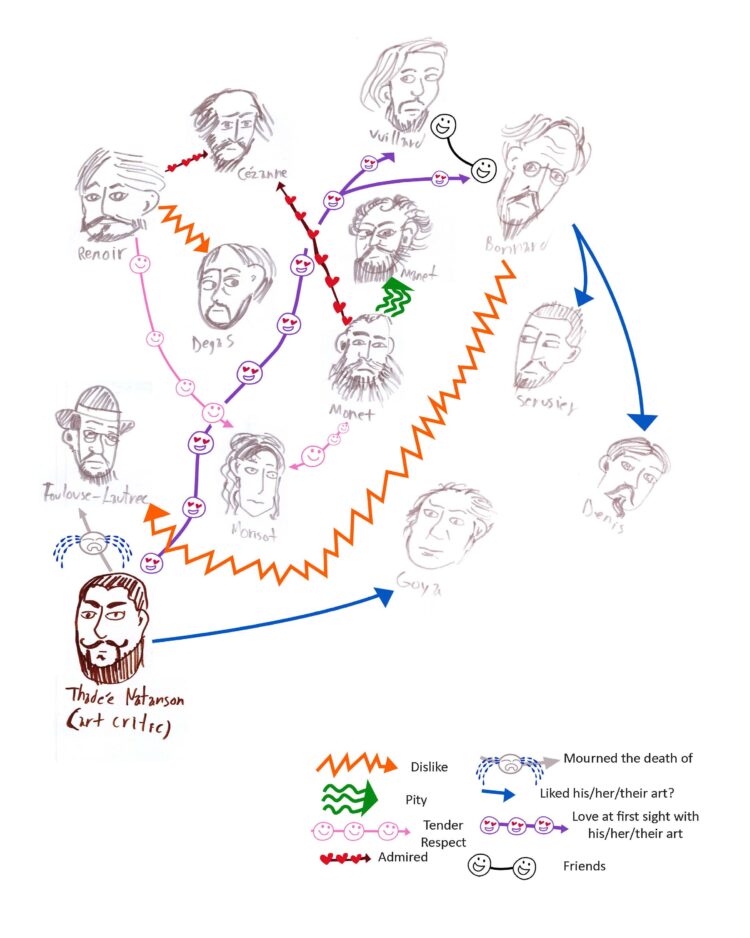

The first chapters discussed how Natanson was exposed to Bonnard’s work and other artists he knew. The information seemed like typical hearsay and maybe even gossip, e.g., “I knew this guy who knew this guy.” I’m a good note-taker, but I’m a terrible memorizer. Sketching out a “relationship chart,” doodling the mentioned artists and the critic, and creating a table to distinguish the relationships really started to help me understand the relationships between the artists. It also helped me make decisions about how I wanted to write this blog.

Impressionist Relationship Chart

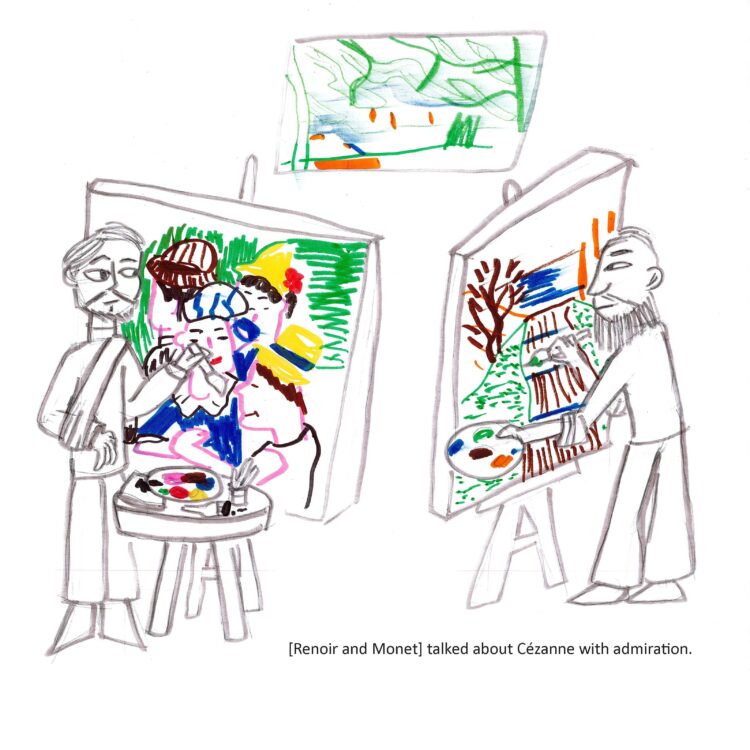

“[Renoir and Monet] talked about Cezanne with admiration.” (page 11)

A red line with hearts was drawn to refer to “X admires Y.” And after looking at the painting styles of the three artists next to one another, it makes sense. Renoir and Monet might have admired Cezanne for his portrayal of landscapes rich in colors, leading them to apply such palettes for their art. Granted, Renoir and Monet certainly had different art styles and themes, but it’s clear that they were both fans of Cezanne.

Renoir-Monet-Cezanne relationship

“[Renoir and Monet talked] about Morisot with a respect nuanced in tenderness.” (page 11)

There is a pink line with smiling faces pointing from the two male artists to the one female artist in my chart. That detail is vague because the information that I have to work with is vague. It is easy to speculate about what this relationship was like. It is possible that Renoir and Monet respected Morisot as an artist. Their styles in painting women seem similar. Maybe the guys viewed her as a sister? But then again, what do we really know? This was from a time period where the most recognized and celebrated artists were usually older white men.

I created a zig-zagged orange line to refer to one artist disliking another, but at the same time I created green wavy arrows to refer to “pity” after I read Natanson’s comments that Renoir disliked Degas, Monet disliked Manet, and Bonnard disliked Toulouse-Lautrec.

“Monet almost spoke about Edouard Manet with pity, and Renoir spoke less about Degas’ painting and more about how the man annoyed him.” (page 11)

Can I blame Monet? Not really. I’m a fan of Manet’s Olympia (1863) and the two artists would potentially be in competition with one another, especially because their names are only different by one vowel. Maybe the fact that Manet was eight years his senior annoyed Monet. Perhaps Monet “pitied” Manet because the latter’s work focused on Realism as well as Impressionism. Maybe it was the stark contrast of their paintings’ themes: Monet’s landscapes vs. Manet’s people.

Monet-Manet relationship

As for Renoir, obviously he didn’t like Degas’s personality for whatever reason. It could have been because Renoir liked to paint social excursions while Degas primarily painted private ballet classes.

“Even from the museum where he contemplated […] a Lautrec, [Bonnard] quickly becomes tired and goes for the door.” (page 18)

Bonnard and Toulouse-Lautrec were both artists for the French magazine La Revue Blanche (The White Magazine), so maybe Bonnard was bored of seeing Lautrec’s work in galleries after seeing it already at work. Perhaps it was about the differences in how they painted nude women! Bonnard always painted naked women in some sort of intimate privacy (he especially liked bathrooms because mirrors and windows are both gateways to reality). Lautrec, well, “Lady Marmalade,” anyone?

“After dazzling us, [Toulouse-Lautrec] left us too soon and [Natanson] had to spend many years thinking about him alone.” (page 12)

A grey line and sobbing face to refer to “X mourning Y.” This is to represent how upset Natanson was when Toulouse-Lautrec died. Toulouse-Lautrec is more of a Post-Impressionist, but he might as well have been a king during the Belle Epoque. The arts gained more recognition and Bohemianism was a trendy way to live. Either Natanson was a fan of Toulouse-Lautrec’s works for the Moulin Rouge or the two got drunk together on absinthe and brothels.

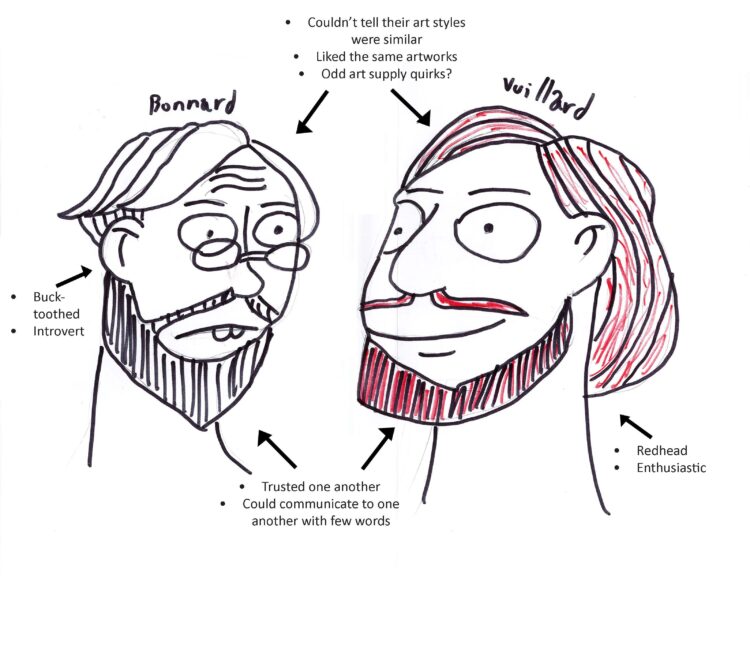

“Vuillard, a friend and comrade of Bonnard.” (page 12)

I drew a line connecting two smiley faces to demonstrate the friendship between Vuillard and Bonnard. The two artists had similar art styles and shared taste. Natanson discusses the trust and easy communication between the two; they would react to each other’s uses of art supplies with delight and passion. Vuillard seems to have been an extroverted fiery redhead and Bonnard was a buck-toothed introvert who read a lot but talked much less.

“The two young painters are eager to show each other everything they do and Vuillard, who is the most enthusiastic, would happily agree to never have another judge… Vuillard, who knows his friend to be suspicious, sometimes refrains from uttering a cry in front of a canvas that Bonnard unrolls before fixing it. Bonnard, in the presence of the cardboard backgrounds that Vuillard has covered, flees, in an attempt at a joke, the trouble, which he avoids, of saying everything he thinks about it. But eyes, even lips, lie much less than words. The two friends look at each other and feel happy.” (pages 26-27)

Bonnard-Vuillard relationship

“For the first Vuillard paintings that I saw and Bonnard’s first small panels, to this day I feel the shock of love at first sight which shook me.” (page 13)

You might notice that there is one unique line that is the only one on the chart. It almost looks like a purple road junction and there are smiley faces with heart eyes. This is to illustrate how Natanson describes the way that seeing Vuillard and Bonnard’s artworks for the first time affected him. He felt the spark that makes the critic decide to support and collect an artist’s portfolio. In a weird way, it’s like the artists are getting the golden buzzer on America’s Got Talent.

Natanson’s relationship with Bonnard and Vuillard’s art

“[Natanson] took an even greater liking to Goya.” (page 17)

“[Bonnard] watched, not without astonishment, the speeches of Paul Serusier or Maurice Denis unfold and took rather precarious support from the silence of Vuillard which he generally felt with him.” (page 20)

I drew an uncertain blue line for “X liking Y’s work.” The second chapter emphasizes Natanson’s interest in Goya’s work but still remains vague about whether or not Bonnard liked Serusier and Denis’s artworks.

CONCLUSION

When you read a 20th-century art critic’s perspective on the artists of his time, it brings up a lot to think about. These geniuses whose works have inspired us and their stories told every year had interactions and thoughts of one another. Maybe the new reveals and still-vague details will make us think more: “How do I see this artist’s work now that I know?” If one man’s perspective on their relationships can give us new lens, will it convince us to explore artists’ relationships in general and how it could have affected their careers/art? This makes me consider researching more about women artists like Morisot to understand how those relationships impacted their careers. Does knowing about the artists’ relationships change the way you see the art? Are you curious about relationships between other artists? We discovered the Impressionists in this blog, so which ones might be next?