The Phillips Collection and the University of Maryland have collaborated to offer “Connecting to the Core Curriculum: Building Teacher Capacity for Arts Integration with Prism.K12.” Now in its second year, this course introduced Prince George’s County Public School teachers to the Phillips’s Prism.K12 methodology. Through a set of six strategies and a suite of online resources, Prism.K12 helps teachers develop rigorous arts-integrated lesson ideas for the classroom. Throughout the semester, students gained a working understanding of how to integrate the visual arts into the K-12 core curriculum using Prism.K12 strategies and tools, as well as online resources. Through in-person and online engagement, the blended learning course allowed for an authentic digital experience that expanded participating teachers’ technological skill sets and familiarity with web and social media platforms. The course offered in-depth professional development for the Maryland-based educator community, which is nationally recognized for its commitment to arts integration and innovative programming.

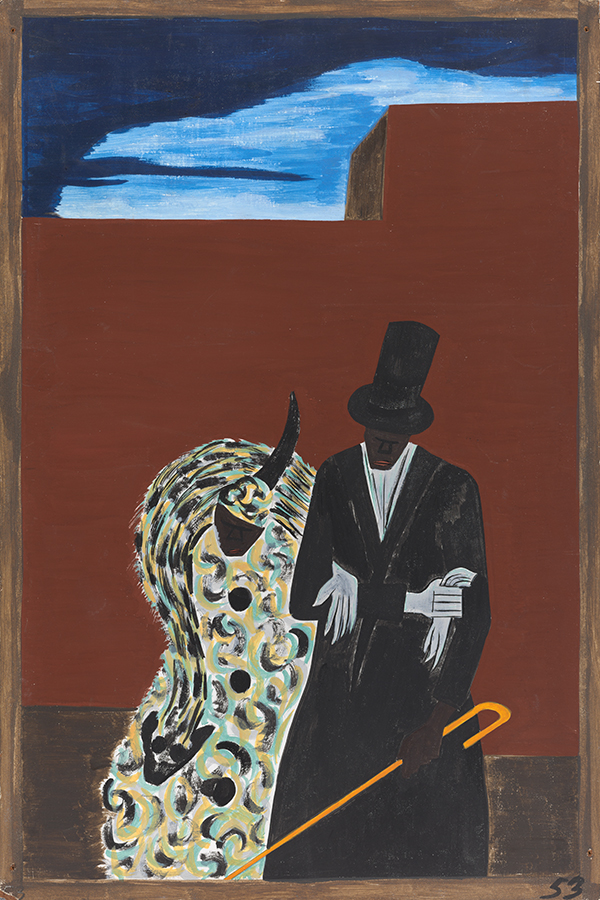

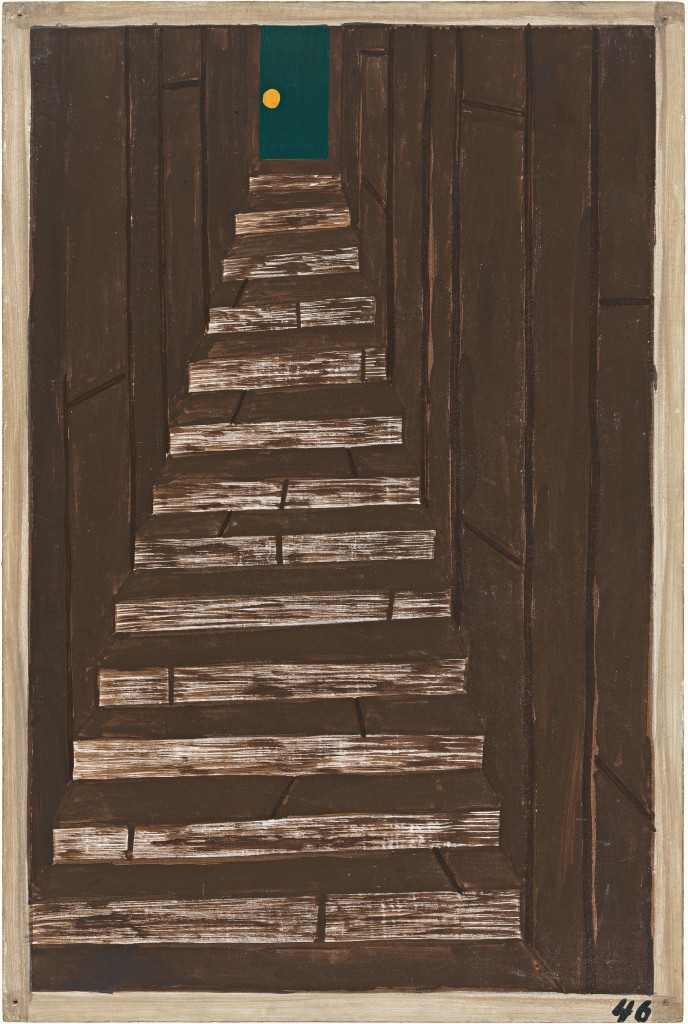

Paul Klee, The Way to the Citadel, 1937, Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 26 3/8 x 22 3/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1940

TEACHER: S. Dmitri Lipczenko

SCHOOL: Glenarden Woods Elementary

CLASS: Visual Art, Grade 3

PRISM.K12 STRATEGIES: Compare, Synthesize

ARTWORK INSPIRATION: Paul Klee, The Way to the Citadel and Castle and Sun, and photos of neighborhoods, cities, and architecture in the US and other parts of the world

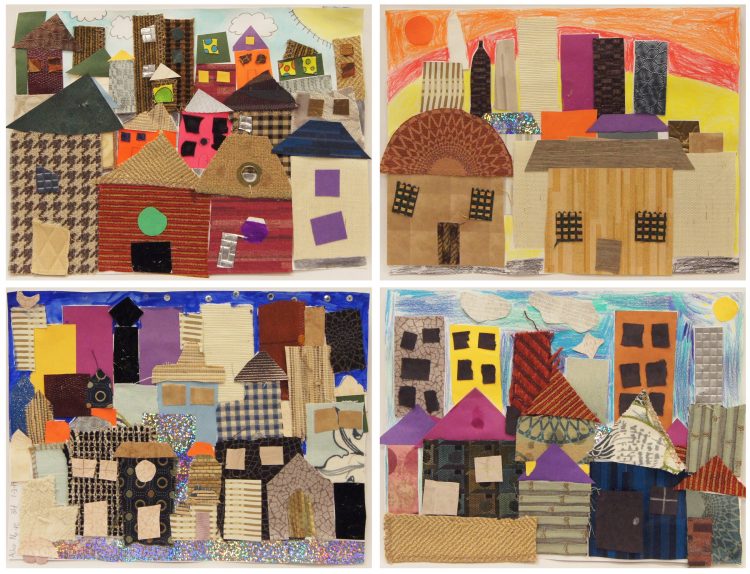

Through this math-integrated art lesson, students created a cityscape collage by cutting and organizing geometric shapes, and used proportions to create a sense of depth/distance. Students studied two paintings by Paul Klee and COMPARED the shapes the artist used in his compositions. They also studied pictures of actual structures to search for “hidden” shapes. Students employed the elements of art for texture and principles of design for proportion. By combining their concepts and skills, students SYNTHESIZED their own cityscape collage.

Samples of artwork from Mr. Lipczenko’s class created in response to Paul Klee’s artwork

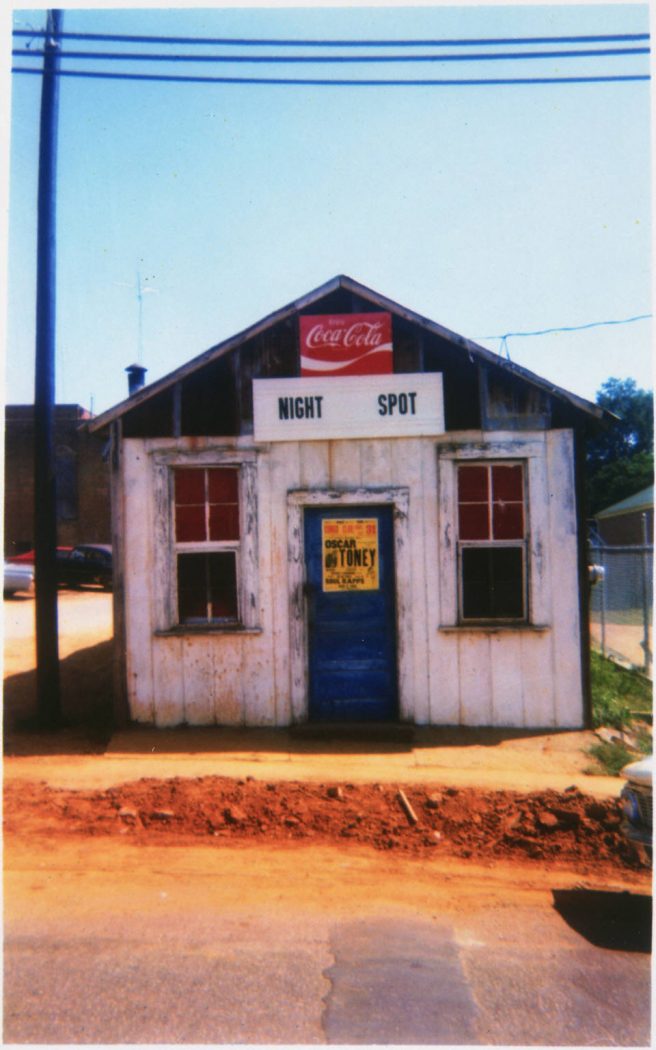

William Christenberry, Night Spot, Marion, Alabama, 1972, 1971/reprinted 1991, Dye transfer photograph, 4 7/8 x 3 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift from the Collection of William and Sandra Christenberry, 2000

TEACHER: Sylvester Felder

SCHOOL: Thomas S. Stone Elementary

CLASS: Art, Grades K-5

PRISM.K12 STRATEGIES: Connect, Express, Synthesize

ARTWORK INSPIRATION: William Christenberry’s photographs

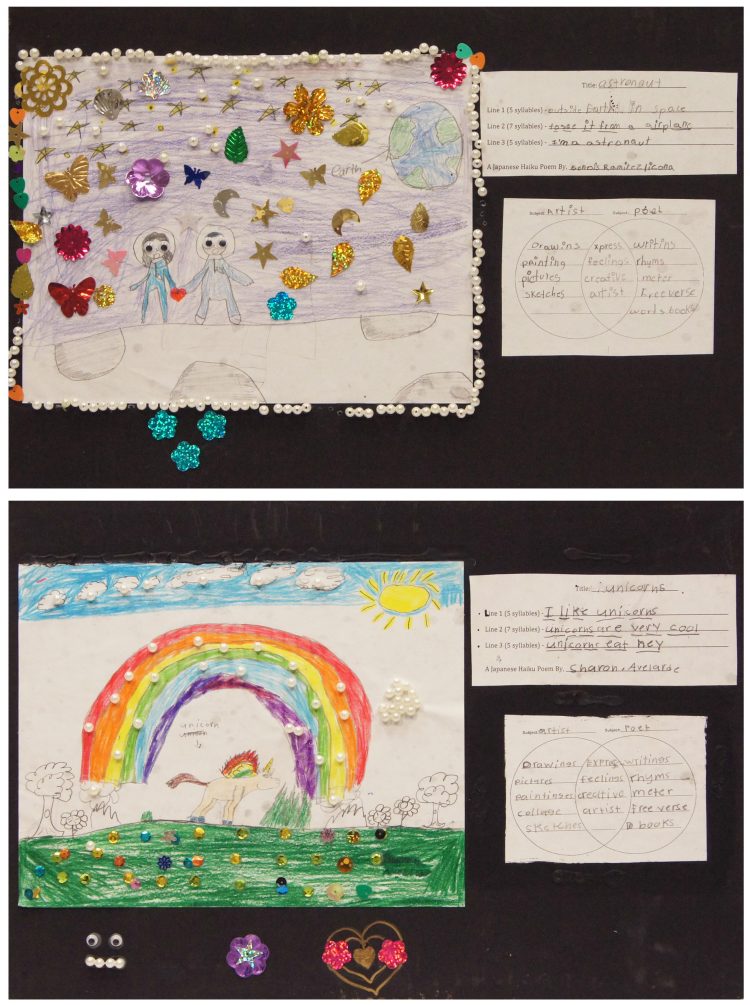

The purpose of this arts-integrated project is to demonstrate the connection between the visual artist and the poet. By studying the photographs of William Christenberry, students are able to see the use of text in his images and further interpret the sense of mood and expression of the subject matter he chose. Students SYNTHESIZED their study of text and mood into artist’s books by combining many elements and aspects of the creative process. They EXPRESSED themselves in their photos and poetry, CONNECTED their theme to their drawings, and used a variety of materials to synthesize their books. Poetic styles include free-verse, diamante, found, and haiku.

Samples of artwork from Mr. Felder’s class created in response to William Christenberry’s artwork

Come visit the Phillips’s Community Exhibition galleries (Sant Building, Lower Level 2) through April 28 to see more student artwork. This exhibition represents the latest efforts in the Phillips’s long standing dedication to arts integration and showcases arts-integrated projects created by students in the classroom through curricula developed by teachers as they progressed through the course.

Learn more about Prism.K12 at teachers.phillipscollection.org