To commemorate Women’s History Month, The Phillips Collection will be celebrating female and female identifying artists during the month of March.

Esther Bubley (b. 1921, Wisconsin; d. 1998, New York) was a documentary photographer and photojournalist known for capturing everyday America. Her black-and-white or color photographs contained striking modernist patterns; one of her many strengths was the ability to construct subtle and complex narratives through sequences of photographs.

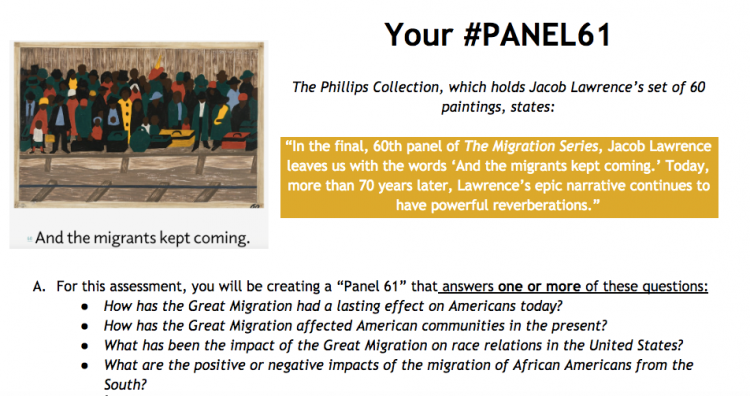

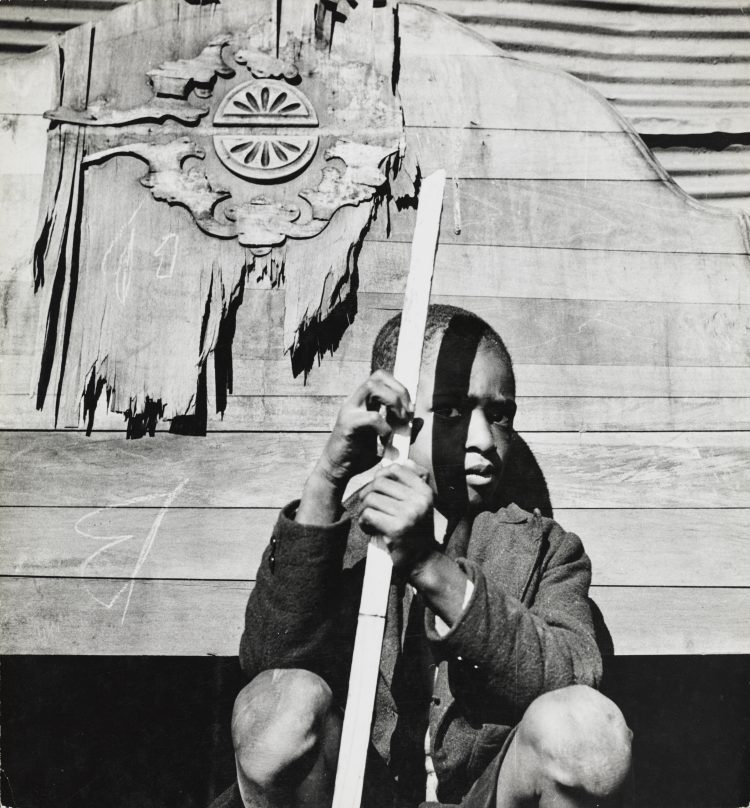

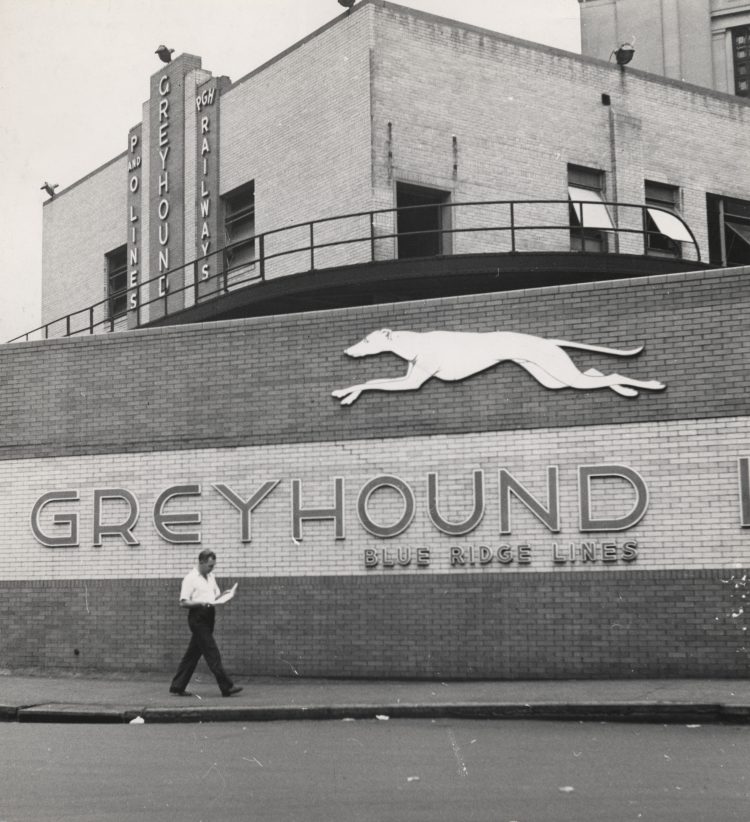

By 1942, Bubley was living in Washington, DC, and working at the Office of War Information (OWI). For OWI, Bubley was asked to document American bus travel, which had dramatically increased due to the rationing of gasoline and tires during World War II. For her 1943 photo story, Bubley spent over four weeks traveling on buses to Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Chicago, Columbus, Cincinnati, Louisville, Memphis, Nashville, Chattanooga, and back to Washington, producing hundreds of images of a country in transition from the Great Depression to a time of war. Bubley focused on the human dimension of mobilization. She carried a “to whom it may concern” letter describing the need for factual photographs of American people needed for progress reports about the war.

Esther Bubley, The exterior of the Greyhound bus terminal (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) (Greyhound Bus Series), 1943, Gelatin silver print, The Phillips Collection, Gift of Robert and Kathi Steinke, 2014

Between 1943 and 1950, Standard Oil (New Jersey) sponsored the largest private sector photographic project ever undertaken in America. Besides depicting operations and illustrating the positive impact of the industry on communities, the photographers also documented topics distantly related to oil, forming a pictorial record of the home front during and after World War II. Bubley used her time on assignment for Standard Oil (New Jersey) to explore more abstract work in photography. She visited the plantation of C. L. Hardy in eastern North Carolina; at the time, Hardy was considered the wealthiest man in the state and the largest tobacco grower in the world, with 12,000 acres in Greene and Pitt counties where 150 tenant families lived. Many of the documentary photographs taken at this moment show the tensions between past and present, rural and urban, man and machine, in the transformation of American life.

Esther Bubley, C.L. Hardy Tobacco Plantation, Maury, NC, 1946, Gelatin silver print, The Phillips Collection, Gift of Cam and Wanda Garner, 2012

Asked to chronicle subjects related to Standard Oil (New Jersey), Bubley photographed women working at Rockefeller Center, the headquarters of the company’s photography project. Located at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the office became a meeting place for the photographers, who freelanced for $150 a week plus expenses.

Esther Bubley, General Service Department, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York City, c. 1950s, Gelatin silver print, The Phillips Collection, Gift of Cam and Wanda Garner, 2012

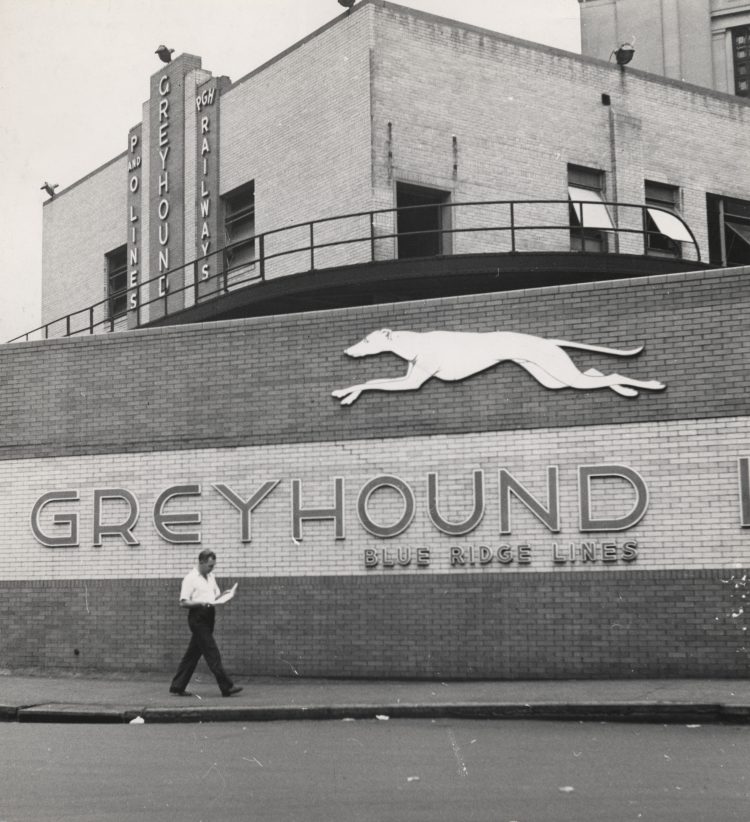

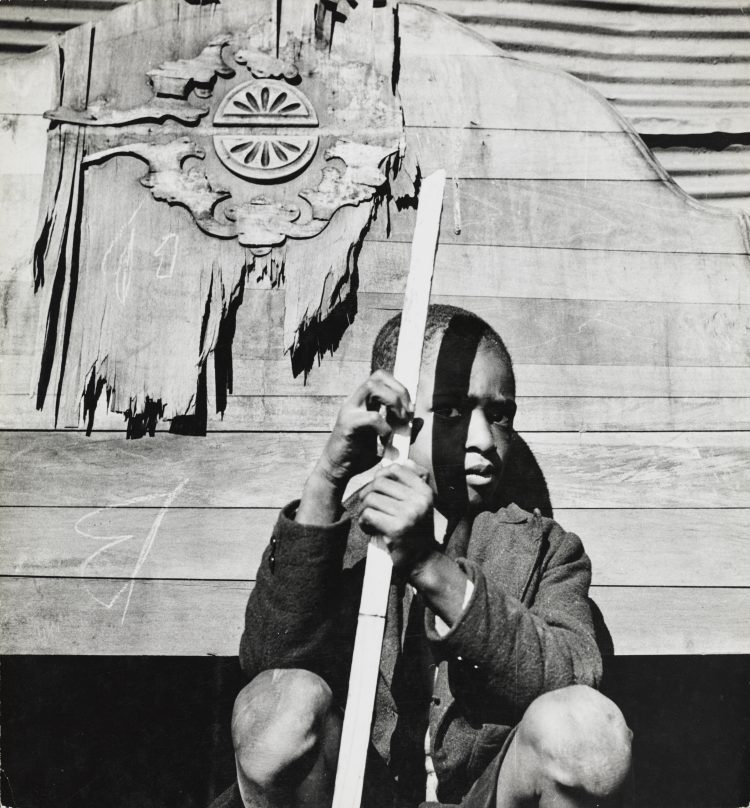

In her off hours, Bubley used a large hand-held Rolleiflex camera to take photographs of subjects that interested her around DC. Her image of a young boy near the US Capitol captures feelings of loneliness and longing. The demand for low cost housing and the lack of affordable transportation for workers was a major contributor to alley dwellings in Washington. Following the creation in 1934 of the Alley Dwelling Authority, the city’s first public housing agency, some alley dwellings disappeared as new housing was created on the edges of the city.

Esther Bubley, A Child Whose Home Is an Alley Dwelling near the Capitol, 1943, Gelatin silver print, The Phillips Collection, Gift of Cam and Wanda Garner, 2012

The Phillips Collection houses over 100 photographs by Esther Bubley. Her prints have been acquired by several museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Library of Congress, Washington, DC; the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; the George Eastman House, Rochester; and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Texas.