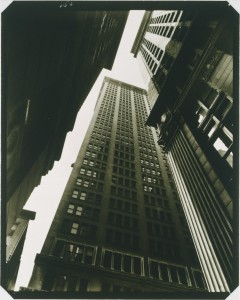

Berenice Abbott, Canyon: Broadway and Exchange Place, 1936. Gelatin silver print, 9 3/8 x 7 1/2 in. Gift of the Phillips Contemporaries, 2001. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

One of the works in the new American Moments: Photographs from The Phillips Collection exhibition is a photograph by Berenice Abbott called Canyon: Broadway and Exchange Place. The image is reminiscent of a canyon because the tall buildings dwarf the camera. The viewer feels miniature in comparison to the surrounding skyscrapers. I particularly like the contrast between light and dark spaces. Daylight is barely streaming through the cracks between buildings, adding to the feeling that the buildings might come tumbling down as they hover above you. The photograph makes me feel claustrophobic, as if I barely have space to breathe when surrounded by such imposing structures.

Studying this exhibition, which includes over 130 photographs by 33 artists, I find that many of the photographs are documentary: what was in the lens is what got photographed. Photography gives viewers an opportunity to compare what is being shown with what is experienced firsthand. Generally speaking, early documentary photographs were often simple to decipher, and they did not typically confuse or frustrate the audience the way other art forms might. In part, this exhibition depicts how photography in the 20th-century was thought of as a window on reality. Even the most educated viewers are inclined to see only the object that is represented, regarding it as the principal subject matter. However, less recognizable are the tools used by a photographer to create a compelling image: the shadows, lighting, and cropping. As Richard Avedon said, “All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.” By using multiple techniques to create a photograph, the artist creates something otherwise not seen by the naked eye.

Almost everyone has used a camera, and therefore, photography might be seen as a more readily available art form of the masses. From its beginning, photography has fought criticism of the medium’s artistic merit. Some critics stated that photography seemed too easy to be art, contending that it was simply a technological way to reproduce what we see. Others argued that photography was one of the highest art forms because artists manipulate the lens of the camera to represent something unseen or missed by the naked eye. Much debate ensued between photographers and those who did not see photography as art. I find this argument among the most compelling and complicated in the entire history of photography—an argument that still goes on today.

Lana Housholder, Gallery Educator