The Phillips celebrates the fifth anniversary of its Intersections contemporary art series with Intersections@5, an exhibition comprising work by 20 of the participating artists. In this blog series, each artist writes about his or her work on view.

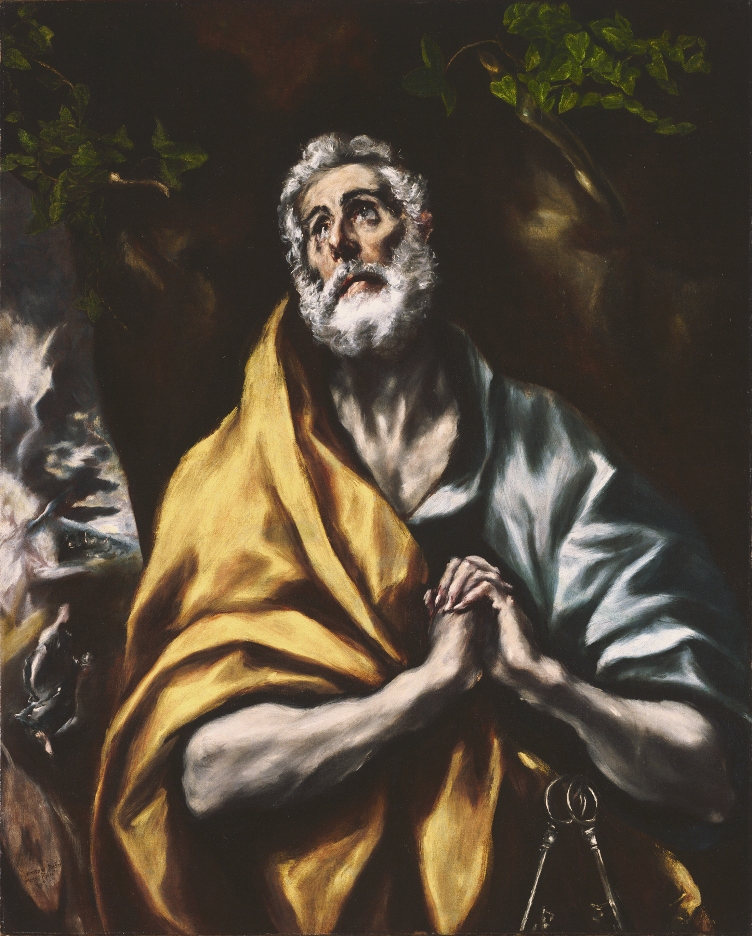

Bernhard Hildebrandt, Peter-4, 2013. Archival inkjet mounted on Dibond, 45 x 80 in. Courtesy of the artist

The camera sees differently than the eye. This distinction is paramount and has long prompted reflection on visual perception as a way of making sense of the world. At the same time, critical writing on contemporary art has sought to map out the various ways that painting, photography, and film serve as a conceptual and often controversial source for one another.

My project examines what I identify as the “kinetic aura” of the Baroque canon. In particular, it investigates the idea of unfolding time through the mediums of photography and video. The work reveals some well-known effects of Baroque art by drawing some as yet unexplored parallels to film making.

Key Baroque themes are considered in a series of images and video looking at illusion and movement. Through analogy with contemporary photographic and cinematic perception, El Greco’s The Repentant St. Peter, can be made to reveal aspects that transcend its own time. His works are inherently imbued with spatial movement, high drama, spectacle and visceral appeal that lend themselves directly to the cinematographic.

Through this lens, El Greco’s The Repentant St. Peter is re-imagined as the repenting St. Peter. We see him actively engaged in his spiritual transmutation.

Bernhard Hildebrandt