David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History is on view through January 9, 2022.

David Driskell was introduced to African art by pioneering artist and art historian James A. Porter at Howard University. Sojourns to Africa in 1969–70 and 1972 deepened his understanding and connection to West African art. In 1973 he addressed this influence directly: “I have turned my attention to images that reflect the exciting expression that is based in the iconography of African art. In so doing, I am not attempting to create African art, instead, I am interested in keeping alive some of the potent symbols that have significant meaning for me as a person of African descent.”

Driskell became a scholar of African art during his tenure at Fisk University in Nashville, where he oversaw an extensive African art collection. Integral to his life, African art graced the artist’s home and his studios. The role of African art in Driskell’s work is rarely one of direct quotation but rather a source of cultural memory and ancestral legacy.

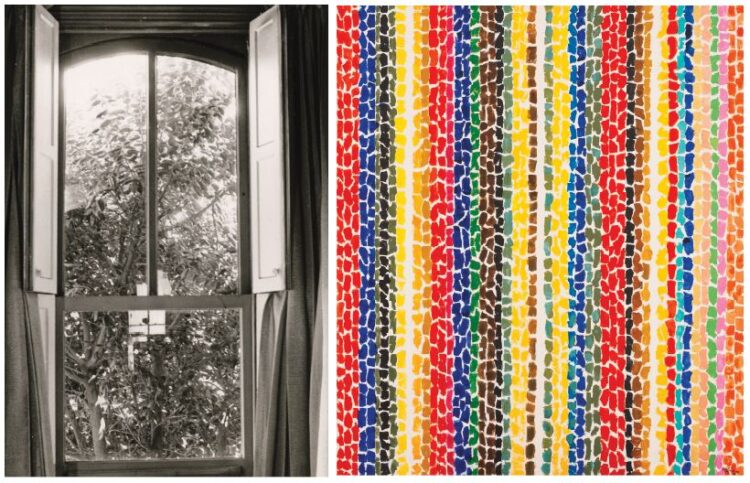

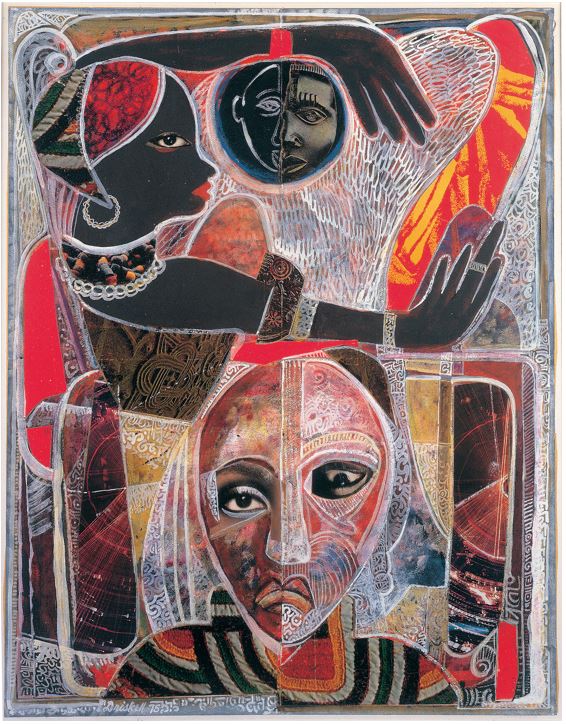

David Driskell, Memories of a Distant Past, 1975, Egg tempera, gouache, and collage on paper, 21 1/2 x 16 in., Private collection © Estate of David C. Driskell

Memories of a Distant Past exemplifies the collage painting method Driskell favored in the late 1960s and 70s, achieving a harmonious orchestration of content and form, paint and collage. Pictorial collage fragments, deployed for pattern and shape, came from commercial print materials (Look magazine was a favorite), fabric, painted paper, and his own uneditioned prints. This painting repurposes material published in the January 7, 1969, edition of Look—a special issue: The Blacks and the Whites. Driskell used pictorial imagery from the essay titled “Black America’s African Heritage.”

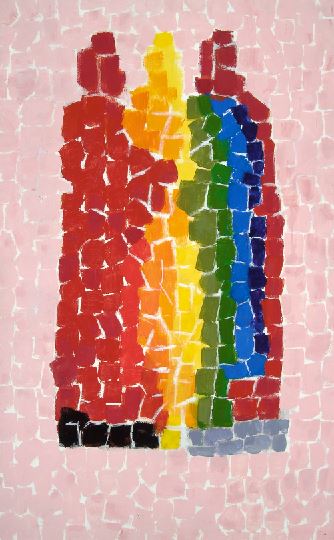

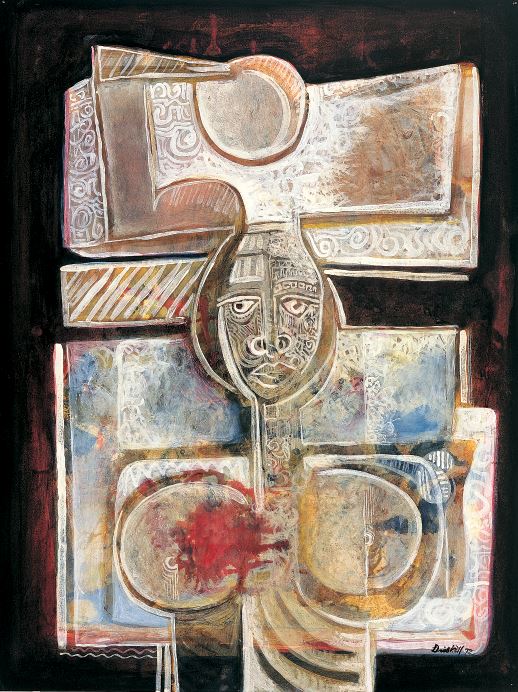

David Driskell, Shango, 1972, Egg tempera and gouache on paper, 24 × 18 in., Collection of the Estate of David C. Driskell, Maryland © Estate of David C. Driskell. Photograph by Stephen Bates

Shango reimagines a Yoruba ritual object, specifically a carved dance wand (oshe shango), as a medieval or Byzantine icon. One of the principal Yoruba deities, Shango, who was known for a fiery temper, controlled thunder and lightning. The double-edged ax that appears above the figure’s head (and on carved dance wands) represents Shango’s lightning. Driskell was intimately familiar with Yoruba iconography from historical studies during his residency at the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) in Ile-Ife, Nigeria, in 1970.