The Phillips Collection is proud to partner with @samesexinthecity to celebrate, honor, and examine Queer art during Pride and beyond. @samesexinthecity explores LGBTQ identity through works in the Phillips’s collection.

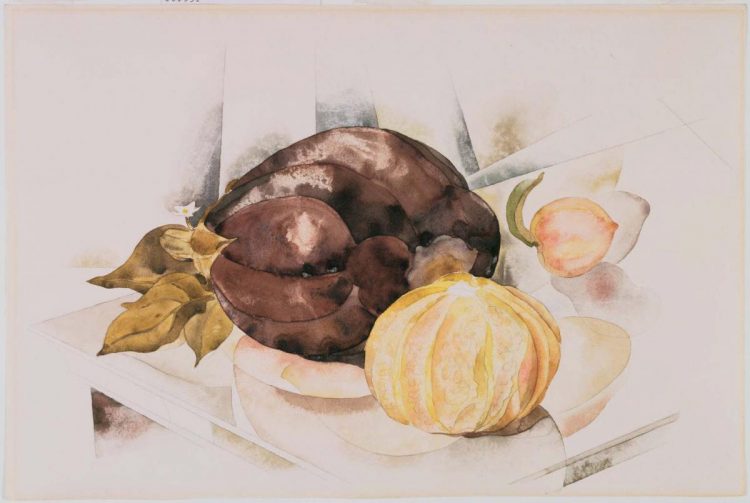

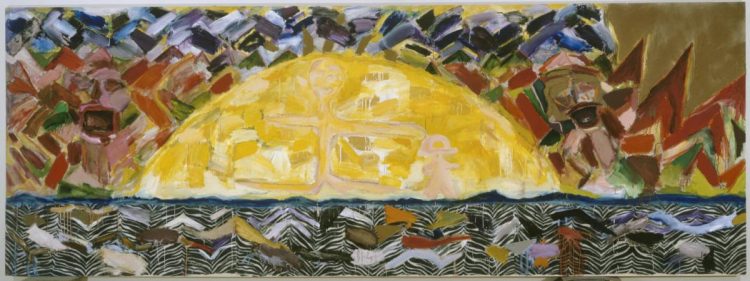

Joan Snyder, Savage Dreams, between 1981 and 1982, Oil, acrylic, and fabric on canvas, 66 x 180 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gifford Phillips in honor of Laughlin Phillips, 1992

Joan Snyder (b. 1940, Highland Park, NJ) first gained attention for her artwork in the 1970s, when she was outspokenly involved in the women’s movement, creating artworks that explored and deconstructed ideas of abstract expressionism, landing on an evolving style that played with pictorialism, incorporating words and letters and personal iconographies. Her artworks are in a number of museum collections, and she has been the recipient of several awards including a MacArthur Fellowship in 2007, a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 1983, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1974.

A vocal feminist, she did not publicly identify as a lesbian until 1980, after a time of confusion, a troubled marriage, and after evolving public success in the art world. In a 1995 interview with fellow artist Harmony Hammond, she noted that she was hesitant about being limited, saying, “Once I began to live honestly and openly, there wasn’t an issue. This was just one part of my life, so I don’t identify that way alone (as a lesbian artist).” However, her artwork is intensely personal, confessional even, incorporating gestural paint strokes, bright colors, and found objects to create a new language.

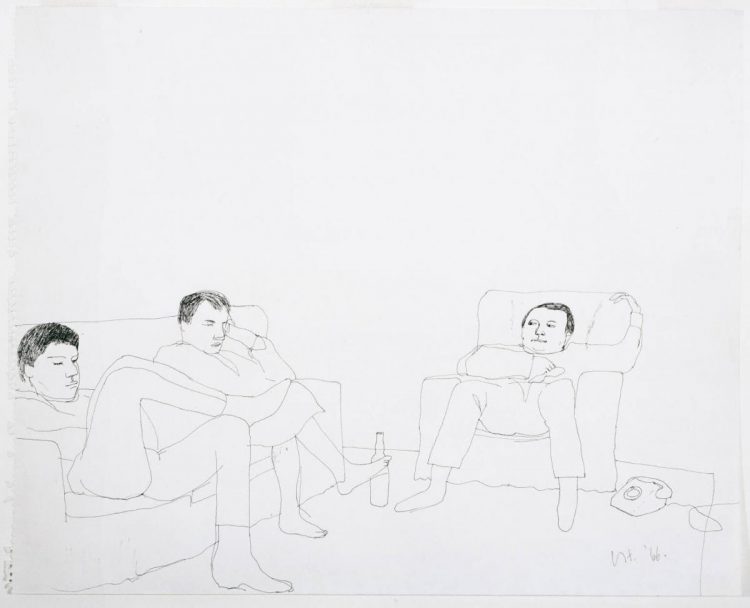

David Hockney, 1996, Three Men, Ink on paper, 40 3/8 x 29 in., The Phillips Collection, Bequest of June P. Carey, 1983

David Hockney (b. 1937, Bradford, United Kingdom) has established himself as one of the leading, versatile artists of the 20th century. Known for his prolific output of works of all mediums—experimenting with everything from acrylic paints, to stage designs, to collaged photography, and more—his explorations of queer life in the 1960s and 1970s remains key to our imagining of gay history at that time.

While doing postgraduate work at London’s Royal College of Art, he was inspired by the writing of Walt Whitman, creating works with titles such as “Erection” and “We Two Boys Together Clinging.” He was intrigued by the differences in response to queerness when he visited America for the first time in 1961, which alongside the easy-going lifestyle led him to move to the United States in 1964. After moving to California, he started painting colorful images, focusing on domestic scenes of men together, among sun-drenched pools and palm trees, showers and bathtubs, and bedrooms in bright, window-filled houses. His artwork was overt in his examination of the male body, blatantly sexual as he depicted gay desire, luxuriating in the white, male nude. In the early 70s, Hockney started double portraits of couples, such as writer Christopher Isherwood and painter Don Bachardy, and Henry Geldzhler and Christopher Scott—portrayals that captured public attention and remain today as key images of the 1970s gay, white scene on the West Coast.

Interested in seeing queer art and histories highlighted even further? Vist @samesexinthecity on Instagram for daily updates!