Head Conservator Elizabeth Steele on the 8-month long conservation treatment of Ellsworth Kelly’s Untitled (EK927).

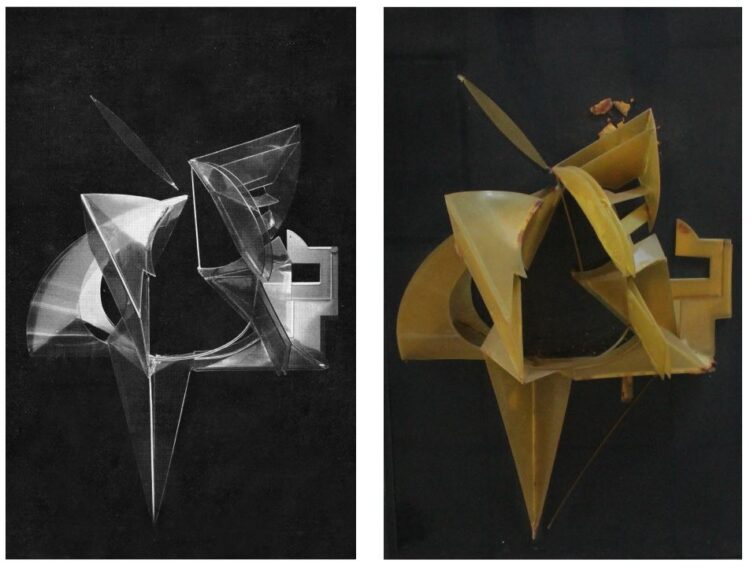

In 2005, to commemorate the opening of the new courtyard at The Phillips Collection, the museum commissioned Ellsworth Kelly to create a site-specific sculpture for its west wall, made possible through the generosity of Phillips Trustee the late Margaret Stuart Hunter. Untitled (EK927) is a large-scale bronze composed of two flat planes that are semi-circular, joined so that one lies parallel to the wall and the other juts forward in a V-shape. It reflects the artist’s enduring interest in reductive abstract shapes drawn from nature and architecture. Kelly oversaw its installation in 2006, deliberately choosing to mount the 1,500-pound sculpture at an angle, making the sculpture seem to defy gravity.

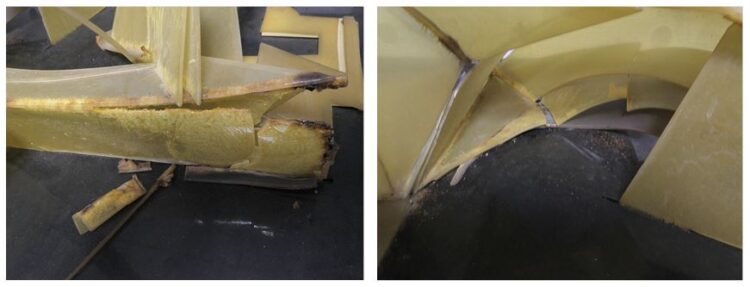

As with all outdoor sculptures, conservation treatments are periodically needed to maintain the work’s intended surface appearance after exposure to nature’s elements that slowly erode applied coatings and patinas over time. Strong sunlight, heat, humidity, freezing temperatures, snow, pollen, and other abrasive airborne particulates, in addition to scratches and rubs acquired over the years, caused the clear lacquer coating on Untitled (EK927) to cloud and the black patina to degrade.

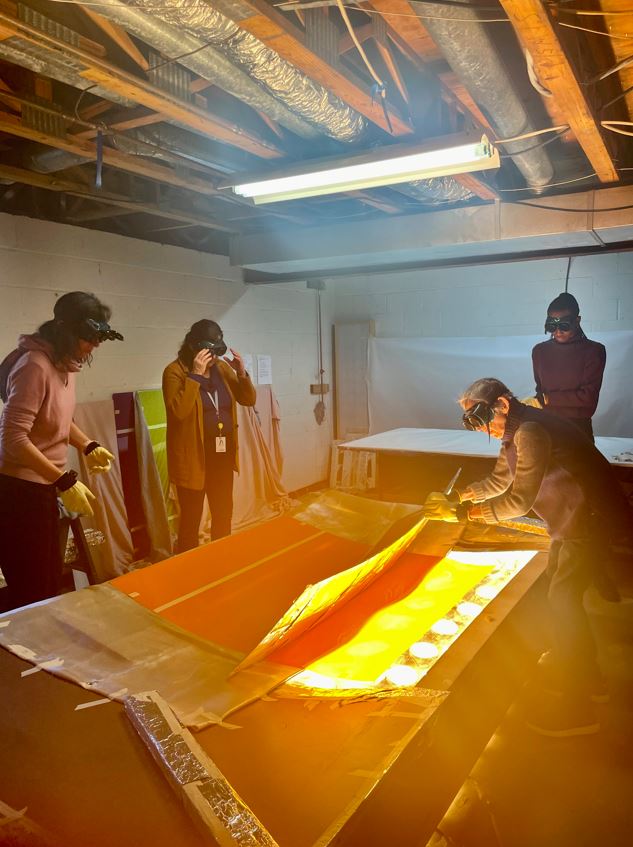

On the advice of sculpture conservators, the Phillips decided to remove the deteriorated surface coating and patina and reapply a new black matte patina. Instead of reapplying a lacquer to protect the patina, the final surface coating of the sculpture is achieved with numerous applications of wax. A custom formulation of Treewax tinted with black pigments was created to maintain the flat matte black appearance desired by Kelly. We are grateful to the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation for underwriting the large-scale conservation treatment to restore this magnificent sculpture to its intended appearance.

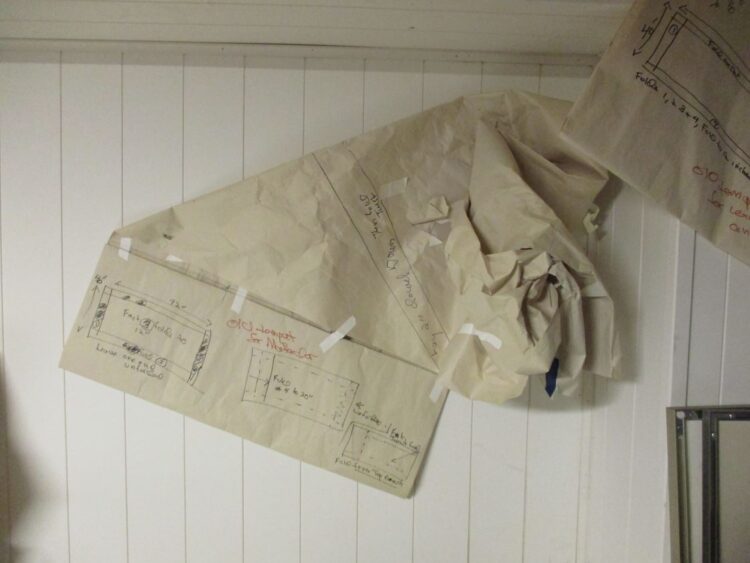

In November 2022, a team of skilled art handlers painstakingly removed the sculpture from the courtyard wall, where it has hung for the past 16 years. Many of the same individuals involved with its initial installation were present. It was taken to ASCo in Manassas, Virginia, which specializes in refinishing outdoor sculptures. After the deteriorated surface was removed, the firm Bronze et al, Ltd reapplied a new patina. The sculpture was then reinstalled June 2023 by the same team of seasoned art handlers. The conservation department will continue to monitor the sculpture, washing it several times a year to remove any accretions and reapplying wax as needed to maintain the artist’s desired surface.