Phillips Educator Carla Freyvogel shares her experiences discussing art…and more…with a group of fifth grade students.

On a school tour with a theme of color, line, and shape, we enter into the gallery showcasing the many works related to the Jefferson Place Gallery. The plan was to look closely at Ben Summerford’s brilliant, tall, still life entitled The Blue Bottle, 1949-51. My lesson plan has us using a visual thinking strategy to look closely at The Blue Bottle, concentrating on the artistic choices made by Summerford.

That is not what my student wanted to discuss at all. Instead, her eyes are drawn to a small assemblage by William Christenberry that hangs on the wall perpendicular to The Blue Bottle.

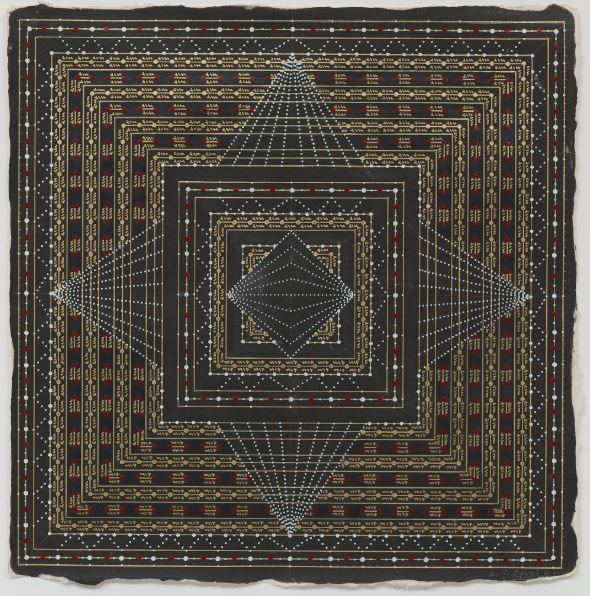

William Christenberry, Akron Wall, 1987, Sheet metal, metal signs, wood, nails, and paint on wood panel, 9 x 12 3/8 x 1 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Julia J. Norrell in memory of Scotty McIntyre, 2009

“I want to talk about that work of art.” She points to the Christenberry. ‘What IS it?”

“What do you think it is?” I ask.

“It looks like a bunch of junk,” she says definitively. “But, I like it. It is interesting.”

We examine the wall text and learn it is called Akron Wall, was made in 1987, and is constructed of sheet metal, metal signs, wood, nails, and paint on wood panel. I explain that Akron is a city in Ohio. We muse about the title, the choice of objects, and its possible meanings.

“What about the rest of the work?” she asks me.

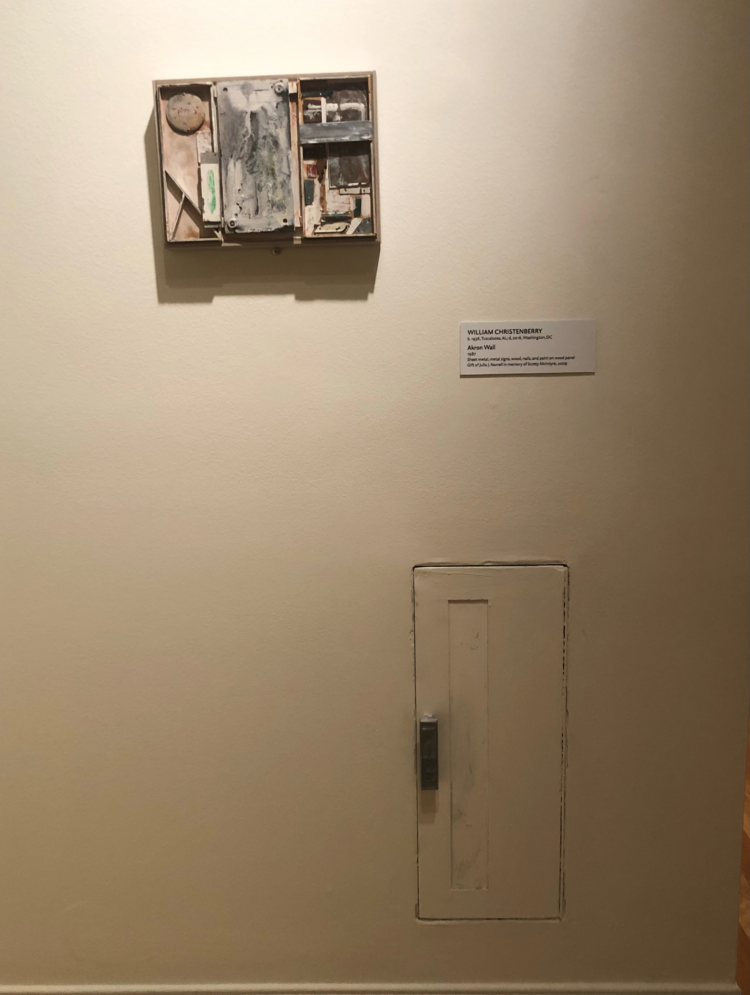

I looked at her, a bit confused. Akron Wall is very intriguing but it is small and contained. She points to a spot on the wall under Akron Wall. There is a tall, narrow rectangle, delineated by a rough edge, chipped and warped in places. A recessed rectangle marks one side along with a metal handle.

“That part of the art. It looks like it could be a door! I want to know about that. I wonder, what is behind the door?”

This door is not part of the artwork. There is a long discussion about what might be behind the door. A little man? A bottle of water? A bag of chips? What would be behind the door? Although the door has the same palette as Christenberry’s assemblage, incorporates metal, has similar repetitive shapes and has gray smudges of a well-worn, maybe found object, I can’t help but spill the beans.

“Well, it is not actually part of the artwork,” I explain. By this time all the students are invested in the door, and they are crestfallen, thinking that they are doing just what I have encouraged them to do: look closely and ask questions, ponder possibilities, and trust their insights since there are no wrong answers.

“It’s not part of the artwork? Well, it should be!” the student says defiantly. “If it is not part of the artwork, what IS it?”

I wanted to talk about the Summerford, not a door in the wall of the gallery. I should have asked the question back to them: “What do you think is behind the door?” But instead I try to guide the conversation back to the original topic I had planned for.

“I think there is a fire extinguisher inside. Now, let’s talk about the colors that Summerford used….”

“Oh man! A fire extinguisher!” someone exclaims. “Woah! Why would you need a fire extinguisher here?”

I could have used the moment to tell him about the fire the Phillips suffered in 2010, but instead I add, “Or a telephone.” Lots of discussion goes on among the students, and they request that I open it. I explain that I’m not allowed to touch the walls of the gallery and open the door.

Looking back on this, I think how intriguing it would be if this door had been conceived by Christenberry. The door introduces the unknown, and the idea of possibility. If there is a phone, who would call it? Could we hear it if it rang? If there is a fire extinguisher in there, would it have some lettering on it? Would the fire extinguisher be red and relate nicely to the worn lettering on the top left of the assemblage (a Coke bottle top)? Is the little space behind the door shallow, like the indented boxes within the Christenberry piece?

We have a brief conversation about the Summerford, the artwork I originally wanted to discuss. In fact, the students’ curiosity seems to have been piqued by the discussion of the possibilities introduced by the evocative door. It reminds me that adapting to students’ interests can ultimately enhance a lesson.

As we walk down to the bus, the student who started the discussion persists; she insists the door should be part of Christenberry’s assemblage: “Then it could be called Akron and Phillips Wall.”