Marketing and Communications Detail and Museum Assistant Caroline Polich on abstract works in the collection.

Abstract art is a genre of art that doesn’t seek to accurately represent reality, instead using a visual language of shapes, colors, marks, and forms. From Color Field to Cubism, and from Suprematism to De Stijl, this genre encompasses many techniques, approaches, and movements. Abstraction has a long and nuanced history across many cultures, but it received new interest and experienced many new developments starting in the early 20th century in Europe. It has played a pivotal role in art and art history ever since. As a museum of modern and contemporary art, The Phillips Collection has a wide variety of abstract works. Learn more below about several artistic approaches to abstraction, exemplified by three paintings in our permanent collection.

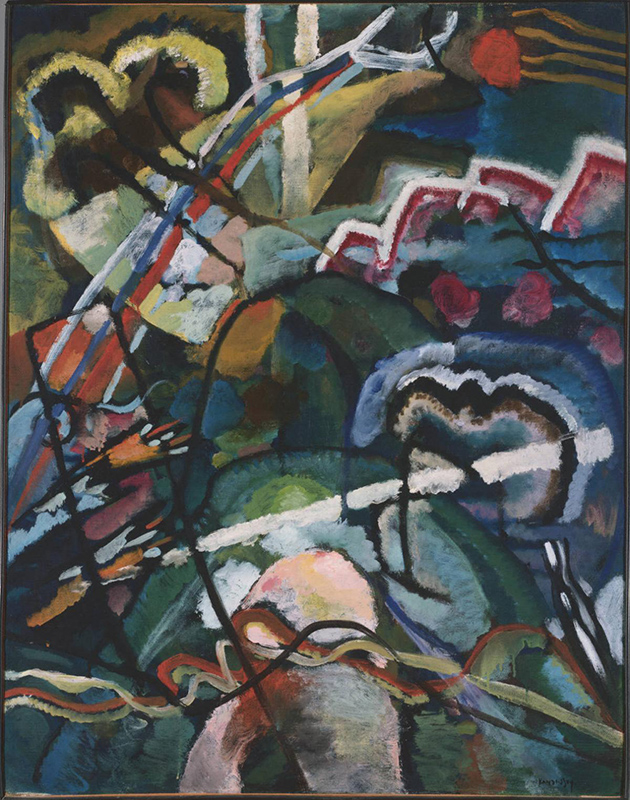

Many artists use abstraction to depict a place in a more profound and multidimensional way. Wassily Kandinsky’s Sketch I for Painting with White Border (Moscow) (1913) uses color, shape, and line to convey the feeling or “emotional sounds” of Moscow. Kandinsky (1866-1944), one of the first Europeans to adopt abstract art, was born in Russia but spent much of his life abroad. In this work, he creates a sense of place through motifs strongly connected to his home country. The three parallel lines in the top left of the composition convey the movement of a troika, a three-horse sled. The undulating brown, black, and white lines on the right, which intersect with a bold white line, represent the legendary figure of St. George on horseback with a lance. Through abstraction, Kandinsky captures the essence of a place, its culture, and his connection to it.

Wassily Kandinsky, Sketch I for Painting with White Border (Moscow), 1913, Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 30 7/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift from the estate of Katherine S. Dreier, 1953

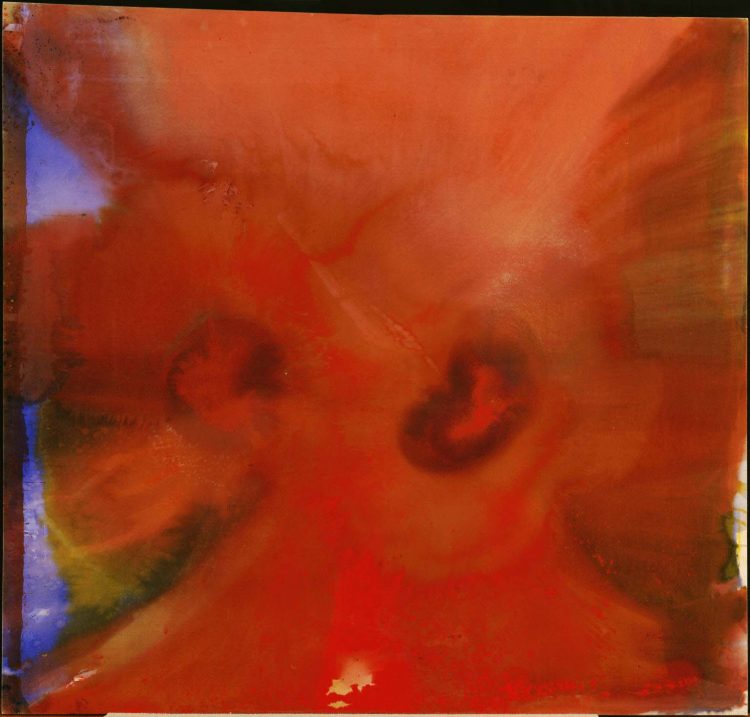

For some artists, abstraction is a way to explore new processes and reinterpret traditional mediums. Sam Gilliam (1933-2022) was known for his draped paintings on unstretched canvas, and his improvisational approach to painting, inspired by jazz. Red Petals (1967) is an early example of Gilliam’s unique process, in which he poured paint over unprimed and unstretched canvas, then folded, rolled, and splattered it to create his vibrant and fluid compositions. The work is a balance between control and chance, the artist’s actions and the properties of the mediums (both the paint, the canvas, and how they interact). Red Petals, unlike many of Gilliam’s later works, was re-stretched so it could be hung on a wall like a traditional painting. However, this work still demonstrates how the artist saw canvas as a medium to engage and create with, not just a two-dimensional surface to paint on. Working abstractly allowed Gilliam to reimagine traditional approaches and processes in painting.

Sam Gilliam, Red Petals, 1967, Acrylic on canvas, 88 x 93 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1967

Other artists use abstraction to visualize intangible or philosophical ideas. Anil Revri (b. 1956) is an Indian artist born in New Delhi, who lives and works in Washington, DC. Revri’s abstract paintings on handmade paper—two of which are recent acquisitions at the Phillips—draw from a wide range of influences, from the Washington Color School to Eastern philosophy. Geometric Abstraction 3 (2020) uses geometry and repetition to explore ideas of meditation, truth, order, and journeys. Symmetry creates a sense of calm and order within the complex composition of shapes, lines, and marks. The contrasts in value and color—scarlet, white, and gold against a dark background—affect how the eye moves around the composition, a sort of visual and perhaps philosophical journey across the surface of the work.

Anil Revri, Geometric Abstraction 3, Mixed media on handmade paper, 18 x 18 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of Nuzhat Sultan, 2021

These works by Kandinsky, Gilliam, and Revri are just three examples of how artists can approach abstraction. This genre has opened up new ways of making and thinking about art that are still being explored today. Next time you see an abstract work, think about how it uses elements like color, shape, and line, what traditions it might be reimagining, and what feelings it elicits.

Read More