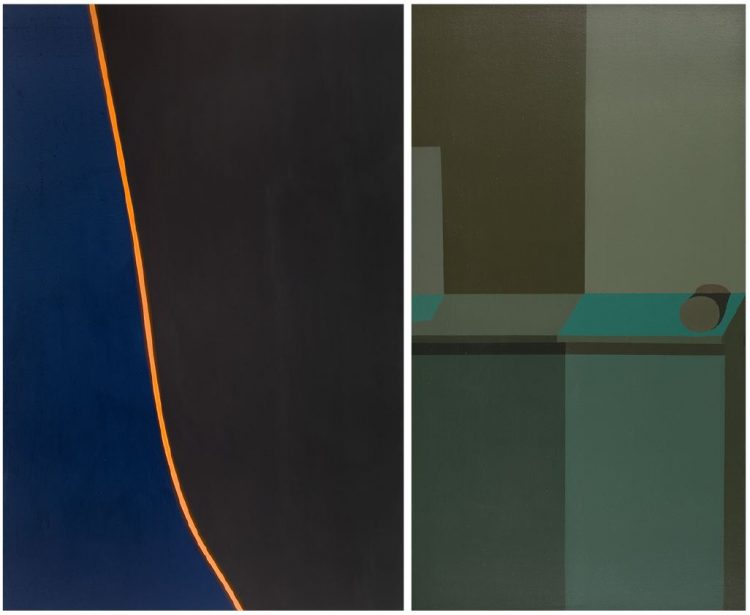

Left: Lorser Feitelson, Untitled (March 14), 1972, Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 40 in. The Phillips Collection, Director’s Discretionary Fund, 2016; Right: Helen Lundeberg, Untitled, 1961, Oil on canvas, 36 x 20 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of The Feitelson/Lundeberg Art Foundation, 2017

Lorser Feitelson (b. Savannah, Georgia, 1898-d. Los Angeles, 1978) and Helen Lundeberg (b. Chicago, 1908-d. Los Angeles, 1999) were two of the most significant forces for the advancement of modern art in Southern California.

Feitelson was an influential teacher, gallery director, WPA mural administrator, collector, and host of a popular television show, “Feitelson on Art.” For decades, his work was overshadowed by the fact that he was living and working in Southern California while critical attention was focused on the New York School. In 1963, Feitelson became interested in the quality of lines as lines rather than as descriptions of forms. The single line became a major motif of Feitelson’s work of the late 1960s and early 1970s. With paintings such as Untitled (March 14), Feitelson was able to show that with the most subtle adjustments of width, volume, and curve, his paintings can be perceived as serene, exciting, lyrical, sensual, or austere.

Feitelson met Lundeberg at the Stickney Memorial School of Art in Pasadena in 1930, where he was her professor. Together they founded Subjective Classicism (also known as Post-Surrealism), a more conceptual version of European Surrealism’s dream worlds. She moved toward abstraction in the 1950s, and her untitled painting depicting angular planes in hues of olive and brown is typical of her mid-century “hard-edge” style.

“These elegant paintings by Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg are important additions to the Phillips’s holdings of California modernism, which also encompasses works by Richard Diebenkorn and Frank Lobdell. They provide visitors and students with a richer and more nuanced view of the history of modern American painting.”-Vradenburg Director and CEO Dorothy Kosinski