The Phillips Collection has recently acquired five Gee’s Bend Quilts from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, created by African American female quiltmakers of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. Dedicated to promoting African American artists and traditions from the southern United States, the Souls Grown Deep Foundation has a large collection of works by the quiltmakers of Gee’s Bend, a remote, historically black community in Alabama. Dating back to the early 20th century, the women of Gee’s Bend have created hundreds of quilts; their uniqueness resulting from geographical isolation and cultural continuity as generations of women developed visual conversations through this artistic process. The quilts, created from recycled clothing and fabrics, feature varying patterns including abstraction, concentric squares, and geometric shapes, and include several levels of symbolism—a visual language that complements the Phillips’s collection of American modernism and broadens our understanding of modern art. The works represented by Souls Grown Deep Foundation reveal the complex history and culture of the African American South, and we are honored to have these stories be part of our growing permanent collection.

The five quilts acquired by the museum were created by Mary Lee Bendolph (b. 1935), Aolar Mosley (1912-1999) , Arlonzia Pettway (1923-2008), Malissia Pettway (1914-1997), and Lucy T. Pettway (1921-2004). Three other institutions have also recently acquired pieces from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation: the Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts.

Souls Grown Deep explains some of the significance of the materials and patterns of the quilts:

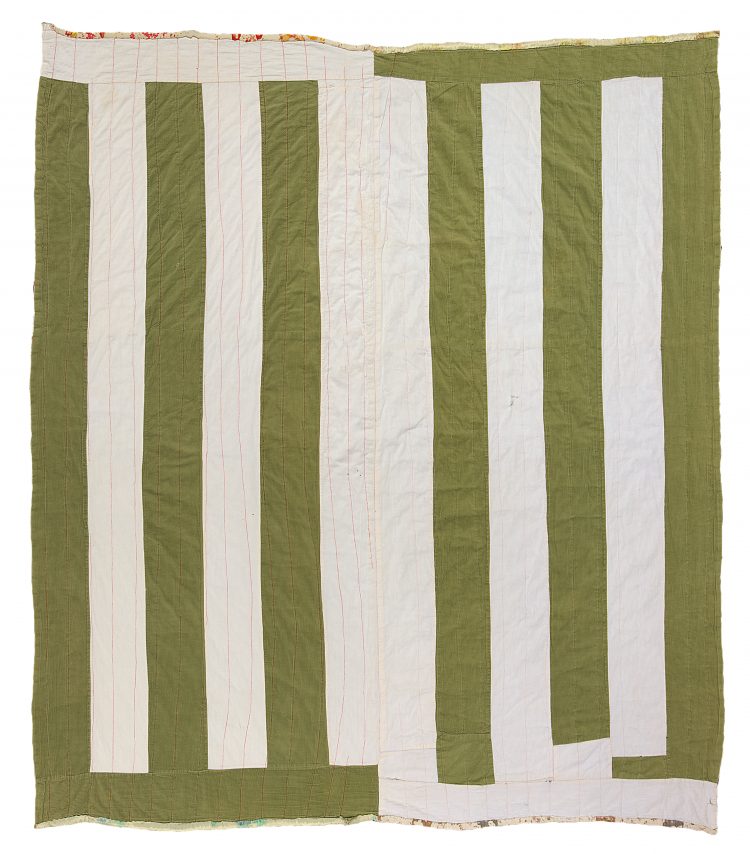

Arlonzia Pettway, Lazy Gals, c. 1975, Corduroy, 89 x 81 in., The Phillips Collection, Museum purchase, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2019, Photo credit Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

In 1972, the Freedom Quilting Bee, a sewing cooperative based in Alberta, Alabama, near Gee’s Bend, secured a contract with Sears, Roebuck to produce corduroy pillow covers. Made of a wide‐wale cotton corduroy, the covers came in a variety of colors including “gold,” “avocado leaf,” “tangerine,” and “cherry red.” Production of the Sears pillow covers left little room for personal creativity, as labor at the Freedom Quilting Bee was divided to maximize daily output. Yet despite the standardized and repetitive process involved in producing the pillow covers, the availability of corduroy, a fabric seldom used before by the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers, stimulated a profound creative response. Leftover lengths and scraps of corduroy were taken home by workers at the Bee. Given to friends and family or bundled for sale within the community, the scraps were then transformed from standardized remnants into vibrant and individualized works of art.

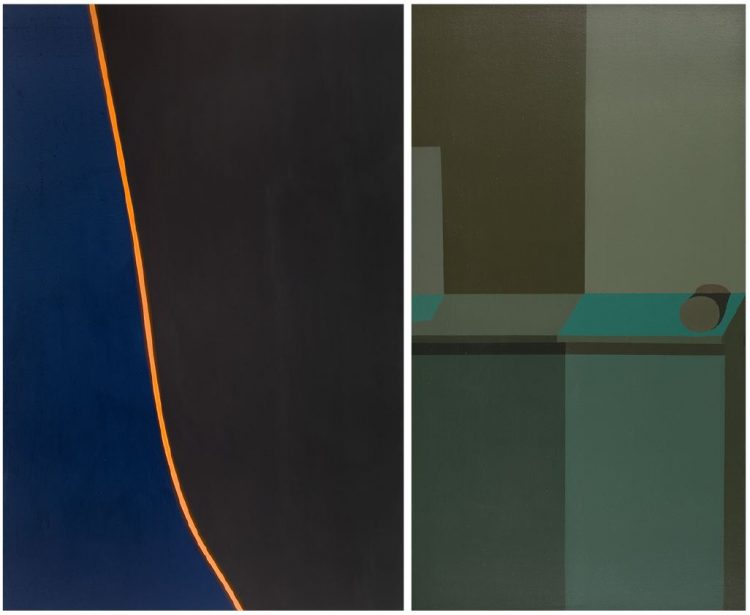

Aolar Mosely, Blocks, c. 1955, Cotton, 75 x 83 in., The Phillips Collection, Museum purchase, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2019, Photo credit Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

Aolar Mosely lost most of her own quilts in a fire in 1984. One of the few to survive is of the most basic and poignant sort, composed of random but more or less rectangular blocks.

Malissia Pettway, Housetop, c. 1960, Cotton, synthetics, corduroy, 81 x 81 in., The Phillips Collection, Museum purchase, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2019. Photo credit Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

Along County Road 29, many women refer to any quilt dominated by concentric squares as a “Housetop,” which reigns as the area’s most favored “pattern.” Its all‐around simplicity hosts many experiments in formal reduction and, at the same time, offers a compositional flexibility unchallenged by other multipiece patterns. The “Housetop,” from the composite block down to its constituent pieces, echoes the right angles of the quilt’s borders, initiating visual exchanges between the work’s edges and what is inside. Traditional African American “call and response,” a ritual technique of music and religious worship, is intrinsic to the target‐like push and pull among elements. The feedback effects have mesmerized and inspired generations of Gee’s Bend quiltmakers. Conceived broadly, the “Housetop” is an attitude, an approach toward form and construction. It begins with a medallion of solid cloth, or one of an endless number of pieced motifs, to anchor the quilt. After that, “Housetops” share the technique of joining rectangular strips of cloth so that the end of a strip’s long side connects to one short side of a neighboring strip, eventually forming a kind of frame surrounding the central patch; increasingly larger frames or borders are added until a block is declared complete.