To pay tribute to the artist’s centenary and his lasting legacy, the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation organized a trip to Kelly’s longtime home and studio in idyllic Spencertown, in Upstate New York. Museum directors, curators, and other art professionals who championed Kelly’s work—the Phillips included—were invited to spend a day at the studio and grounds, view exhibitions of rarely seen work and ephemera and the newly open Ellsworth Kelly Library, and enjoy a luncheon, all in celebration of the artist’s life and work.

Vesela Sretenovic—who in 2013 curated the exhibition Ellsworth Kelly: Panel Paintings 2004-2009—and Bridget Zangueneh—who facilitated the conservation grant for Untitled (EK 927) from the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation—represented The Phillips Collection. Vesela and Bridget share their experience.

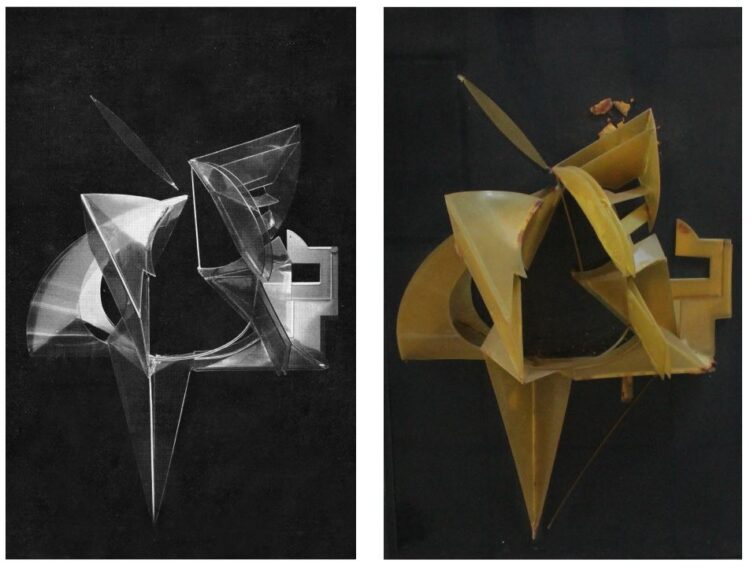

Ellsworth Kelly, Untitled (EK 927), 2005, in the Phillips’s Hunter Courtyard, Commissioned in honor of Alice and Pamela Creighton, beloved daughters of Margaret Stuart Hunter, 2006. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

Installation view of Ellsworth Kelly: Panel Paintings, 2004-2009.

Vesela Sretenovic, Director of Contemporary Art Initiatives and Academic Affairs:

“While walking around Kelly’s studio, the indoor galleries and outdoor grounds, it struck me that the key to experiencing the artist’s work is through a set of interrelationships, first within his own art among shape, color, volume, and space, and then outside of it among the object, oneself, and the surroundings. Being on the site of his creative life, in the midst of art, architecture, and nature only further enhanced that experience. The glorious spring day—May 16, 2023—will be remembered for the lifetime. It also brought back memories from 10 years ago while visiting the studio and meeting the artist in preparation for the Phillips exhibition that marked his 90th year. I remain grateful for these extraordinary opportunities.”

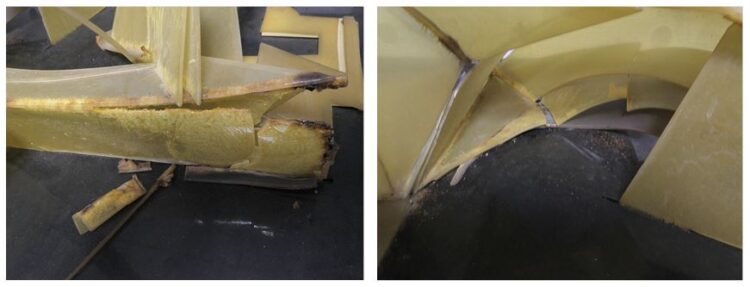

Ellsworth Kelly Studio grounds in Spencertown, NY

Bridget Zangueneh, Director for Foundation, Government & Corporate Affairs:

“It was the light that struck me. The Hudson River Valley sun filtered through precisely-placed windows, skylights, and scrims, above, below, and around, infusing the space with the clearest, brightest light. And the spaces. Open rectangular boxes filled with the bright light. And the art, the works that Ellsworth Kelly created in these spaces, seeing them as he saw them. It was profound. His creations—most finished, some not—were indoors, impeccably placed on walls; outdoors, emerging from the grounds as part of the landscape; and on screens with dancers in motion re-creating Kelly’s iconic shapes with their bodies. All of Kelly’s works, no matter where they were displayed throughout the estate, incorporated the same minimal elements of line, form, and color that are so uniquely his.

Bridget Zangueneh at Ellsworth Kelly’s studio in Spencertown

It was moving, personally and professionally, to be in his studio and on his estate in the presence of his widower and champion, Jack Shear, museum directors, artists, curators, and colleagues. Everyone there was a part of Kelly’s life and entrusted with carrying on his legacy.

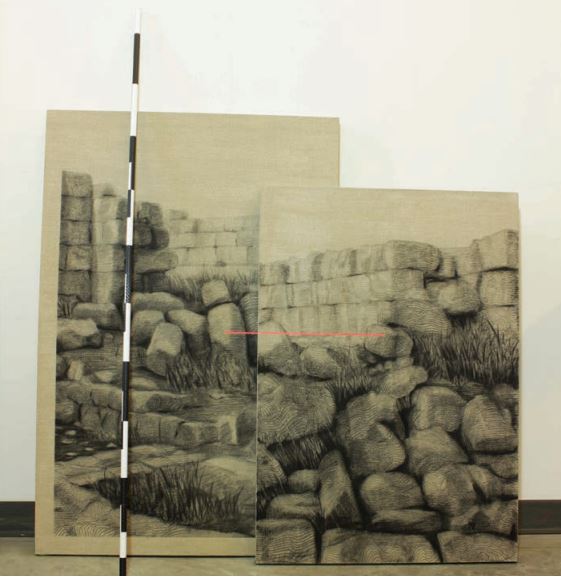

Soon after I joined the Phillips in 2012, the museum was planning Ellsworth Kelly: Panel Paintings 2004-2009 (June 22–September 22, 2013), an installation of seven large-scale works featuring a spectrum of colors and geometric forms that have dominated Kelly’s prolific career in celebration of the artist’s 90th birthday. It was featured in the gallery with 18-foot ceilings, the only Phillips space that somewhat resembles the artist’s studio—an open rectangular box with windows that shepherd in natural light—though I didn’t know that at the time. I’m not an artist, curator, or art historian, and much of “The Art World” was new to me. I appreciate minimalism and, on the surface, enjoyed the exhibition. And then I kept looking. And visiting and revisiting the panel paintings on each walk to the library, courtyard, or offices to look some more. At one point someone recommended that I also look at the space between the paintings. I’d never considered that approach and was astonished. How can anyone evoke artistry from “the space between the paintings”? Kelly did it masterfully, and I’ve never looked at them the same.

One of my stops in the gallery was less of a visit and more of a peek: Ellsworth Kelly was visiting. He was right there in the gallery with natural light observing the exhibition—his exhibition—and conversing with then director Dorothy Kosinski and exhibition curator Vesela Sretenovic, an excerpt of which was posted here on the blog 10 years ago. On the recent trip to Kelly’s Spencertown studio, Vesela underscored that with the Panel Paintings exhibition, and really all of Kelly’s installations, that placement is down to the millimeter. Unfortunately, because of his health at the time, he was unable to be present for the installation at the Phillips. His expert team, our expert preparators, and Vesela installed it with guidance from Kelly via Skype (Zoom wasn’t a “thing” yet), and piece by piece he perfected the precise placements his art required—and the spaces between, “using the wall as part of the painting,” he says. I didn’t stay long. I didn’t dare interrupt. I didn’t say hi. But I was there in my quiet way observing. That experience made a mark on me.

Since that time, I’ve had the pleasure of working with the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation to secure and steward generous grant awards with Phillips colleagues and keep the foundation folks apprised of Phillips activities. But to be at the Foundation, experience Kelly’s studio and spaces, and hear from those who were part of Kelly’s life was deeply inspiring in a way that no museum visit, conversation, or letter could be. It was a full-circle moment, thinking back to my experience peeking into Panel Paintings 10 years ago. Though not an artist, curator, or art historian, I’m grateful to work with those who are, especially as we celebrate and steward legacies like Kelly’s.”