Sherman Fairchild Fellow Ariana Kaye on Jeanne Silverthorne’s artistic process.

On March 24, I had the pleasure of attending a virtual meditation and spotlight on Jeanne Silverthorne’s Dandelion Clock, guided by yoga teacher Aparna Sadananda and Phillips educator Donna Jonte as part of their weekly meditation series. This week was particularly special, as we got to hear from the artist herself after deep reflection and contemplation of her work.

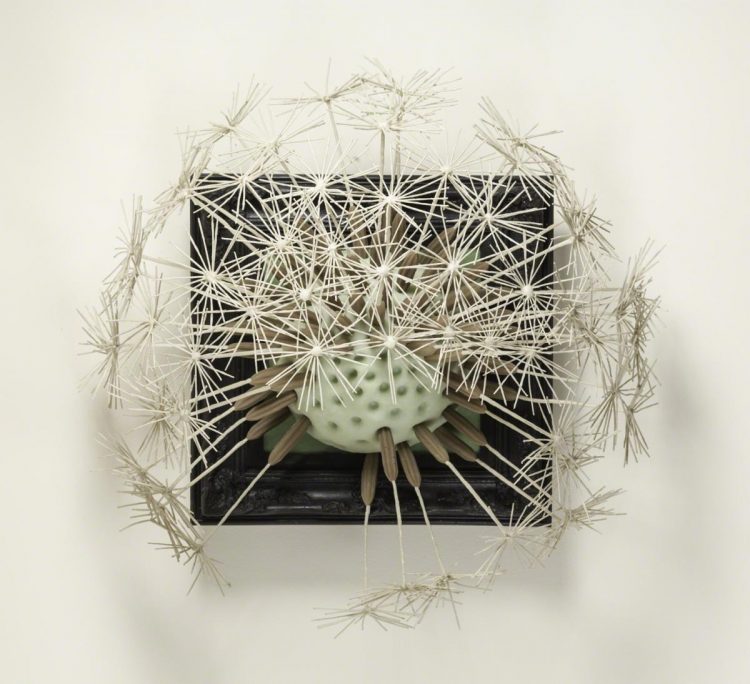

Jeanne Silverthorne, Dandelion Clock, 2012, Platinum silicone rubber, phosphorescent pigment, and wire, 33 x 29 x 16 in., The Phillips Collection, Purchase, The Hereward Lester Cooke Memorial Fund, 2014

Jeanne Silverthorne first presented her work at the Phillips in 2013 as part of Intersections, a series in which contemporary artists engage the museum’s collection and architecture in different ways, creating aesthetically and conceptually diverse projects and employing varied media and approaches. Silverthorne paired 15 of her sculptures with 10 still life paintings from The Phillips Collection for her “intersection.” She titled it Vanitas!, referring to the transience of life and our mortality, while suggesting renewal and possibility, a “becoming and an undoing.” The clock in the title refers to the becoming and undoing of the dandelion, between its inception and its disappearance in nature.

During the spotlight talk, Silverthorne shared her artistic practice. She began using rubber in the 1970s after she walked into an art supply store and saw a bottle of latex rubber. She had previously been using hard plaster, but it was heavy and brittle, so after using latex rubber one time, she loved it. It is a material that cannot be broken, retains a sense of liquidity, and resembles a flesh-like material as it flops around unless it is arranged it in a particular shape. To create her rubber sculptures, Silverthorne starts with clay, modeling the shape of what she wants to create. On top of the clay, she constructs a rubber mold. When the mold is hard, she removes the clay, leaving a negative impression of the rubber. She then adds a release agent (such as Vaseline) so that what she pours into the mold doesn’t stick to it. She pours premium silicone rubber into the mold in different colors and leaves it in for 30 minutes to 16 hours.

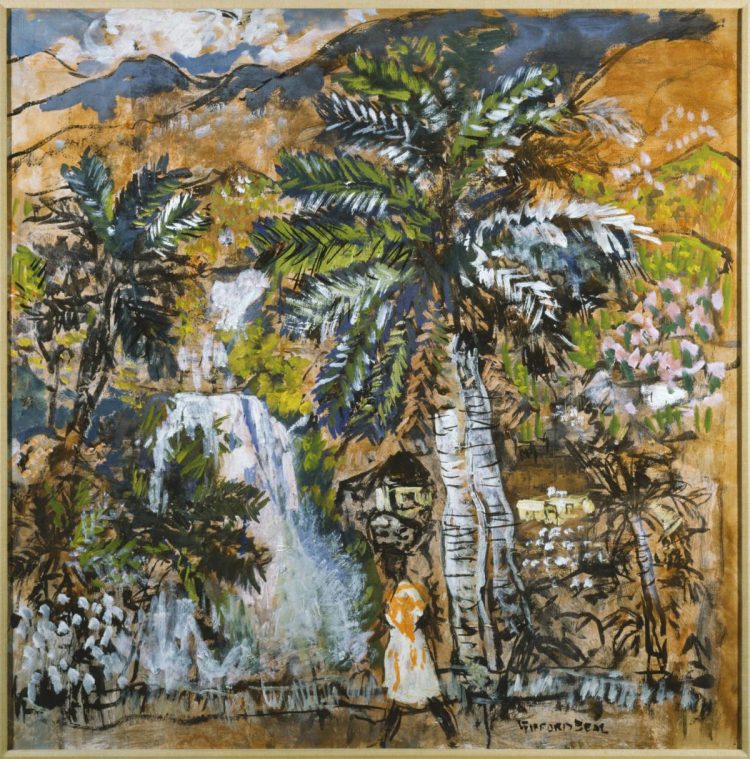

The mixing table in Silverthorne’s studio, courtesy of the artist: “What is pictured are the buckets for the two-part silicone rubber, some silicone thinner to make the rubber flow better into narrow spaces, various pigments, and a couple of newly cast rubber hemlock flowers, part of a piece under construction.”

Silverthorne has been casting dandelions out of rubber for years. The flowers of the dandelion are made through a meticulous process of coating each white part of the flower in rubber, and the brown parts of the stem are cast in a mold replicated over 20 times. The rubber has phosphorus in it, making it glow in the dark, which, for Silverthorne, represents the perseverance of life after darkness and hardship. At the end of a tough time, there is hope.

The work itself is an enlargement of the dandelion. Silverthorne makes most of her works either in miniature or extra large. She quotes her rationale from William James: “We learn most of the thing from viewing it under a microscope or in its most exaggerated form.” By looking at the dandelion in its large form, we learn about the intricacies of the flower. Silverthorne recently found out that you can make rubber itself from a dandelion! Dandelions emit a juice of latex, and latex is rubber. The juice that dandelions emit presents a hope for the use of more eco-friendly materials. Silverthorne mentioned that people have been using plants to make rubber for centuries.

The artist also shared the vast historical significance of dandelions as well as some interesting facts about the plant: Dandelions can remain in place for up to 16 years. Each piece of fluff can make hundreds more dandelions. Flowers are common symbols: roses connote love; dandelions signify fate and chance. The game “She loves me, she loves me not” (now usually played with a flower with petals) used to be played on a dandelion: A person would think about someone, then blow on each fluff, ending up with a prophecy about whether or not they are loved by the person they were thinking about. Additionally, the dandelion (in its flower form) was called the “shepherd’s timepiece” or the “shepherd’s clock” because the petals of the dandelion open when the sun rises and close during darkness. Shepherds were so attuned to this process that it helped them figure out the time of day.

To learn more about artists from the collection through a lens of wellness, join us for Aparna Sadananda and Donna Jonte’s weekly meditation, every Wednesday at 12:45 pm on Zoom.