Ahead of vocalist Joshua Banbury’s and pianist Aaron Diehl’s performance at the Phillips on January 15 exploring the music of Julius Eastman and Billy Strayhorn, the Phillips Music team asked the artists about their collaboration and the fascinating commonalities between Eastman and Strayhorn.

The program features three works by Julius Eastman (1940-1990), an underrecognized queer, Black composer and performer whose work is now experiencing a revival. Many of Eastman’s pieces featured politically and culturally provocative titles, some of which will be performed by Joshua Banbury and Aaron Diehl in the upcoming concert. We recognize the visceral distress and upsetting nature of racially charged language no matter the context and felt it was important to give readers due notice. This Q&A includes multiple citations of offensive language.

Q: What has been the trajectory of this collaboration for you both? What drew you to this particular program and pairing between the music of Billy Strayhorn and Julius Eastman?

JB: There are a few things that inspired me to put this program together. The first is that in choosing to pay tribute to these great artists, I am in essence asking for their blessings. Although we are not related, I feel an ancestral connection. Without their legacy I would not have the opportunity to build my own.

Strayhorn has always mystified me as a figure simply because even 56 years after his death in 1967, he remains one of the only queer figures in the history of American Jazz. The same goes for Eastman in the world of new music.

Being that I am also gay and Black, in thinking about who I should pay tribute to at this early stage of my career, it felt very natural and necessary to do an extended meditation on his work. Of course, I have also been deeply captivated by his music. When I first started entertaining the idea of working in jazz, some of the first standards I fell in love with were written by Strayhorn. His music infuses both jazz and classical idioms so beautifully.

Having spent my early musical education studying chanson, arias and lieder, Strayhorn’s music has always felt intuitive to me. In addition to his music, Strayhorn had a unique way with words, I think his linguistic abilities are best shown in “Lush Life” which is perhaps my favorite composition of his, it hits very close to home.

Eastman, on the other hand, served as a great inspiration for my work as an opera librettist. I gained a lot of respect for his radically unapologetic and uncompromising approach towards reform and Black/queer visibility in American classical music. Eastman’s legacy challenged me to have a sense of urgency and integrity to my own work as both singer and librettist.

Q: You’ve talked about the parallels in identity between your own artistic journey and that of Billy Strayhorn and Julius Eastman. For both artists it seems as if there is a complex relationship between their social identities (race, gender, sexuality) and their sonic identities inscribed in music. How would you trace that line between the two? How might a queer sensibility manifest musically?

JB: The queer sensibility manifests in a few ways, because of course the queer experience is a complex one. It can pendulate from rage and malaise found in “Evil N” to an extended meditation on beauty in Strayhorn’s “A Flower is A Lovesome Thing.”

Strayhorn’s queer sensibility lies right beneath the surface of his work and is immediately apparent if you know where to look. He hints at it with his use of the pink flamingos, blue gardenias, and the distingué girls with jazz and cocktails. But there is also deeper meaning to these images and what they represent, of course.

“Lush Life” or “Sophisticated Lady,” to me, is the epitome of the queer sensibility: the affinity for things that are foreign, beautiful, mysterious, and mystic. The desire to be far away from all that oppresses you in exotic places like Paris…or New York’s punk downtown scene in the 70s. Furthermore, there is often a queer sensibility to romanticize suffering in the queer community. Is it because we fear life will always be unkind to us, so we romanticize turmoil as a sophisticated coping mechanism? In this romanization, does it sometimes cross over into addiction? I believe this may have been the case for both Strayhorn and Eastman, and even for myself.

In my own experience, meditating on beauty and dreaming of grandeur is absolutely necessary in order to maintain a semblance of sanity in the queer experience. Strayhorn’s “Something to Live For” tells a narrative of someone who is searching for someone to make their life “an adventurous dream.” As if to say, love is the only thing worth living for.

The queer sensibility also manifests as a need for reinvention. Both men took to New York City to reinvent themselves. Strayhorn famously took the A train to Ellington’s Harlem apartment to begin their legendary partnership, and Eastman took to the downtown scene to experiment in punk rock movement happening at the time.

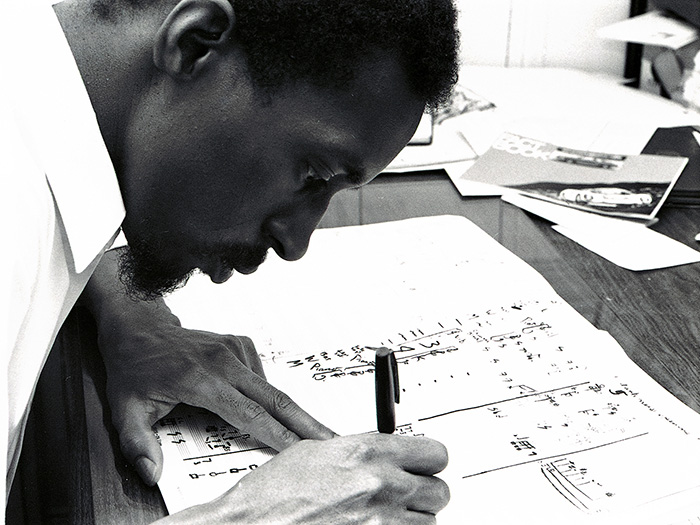

Composer Julius Eastman. Credit: Donald Burkhardt

Eastman’s “Gay Guerrilla” uses a militant, stabbing rhythm to simulate the sounds of a battlefield. His life was also a battlefield, he upset many, and continually fought against forces that were intent on smothering his identity within the American classical music scene. And yet, as his brother Gerry Eastman told me this weekend (January 7-8, 2023) at his jazz club, Williamsburg Music Center, “Julius was the darling of the new music world.” And yet his legacy was nearly forgotten after his death, his music lost after he was evicted, confiscated by the police. Gerry said “he should still be here with us.” It struck me so deeply that he really should. His brother is in his seventies, still rocking out, inspiring the new generation. I was so immensely grateful to play with him that night. I left feeling so enriched, but still wished that Julius was around to have a drink with me and share his thoughts on music and life.

This is why a retrospective on his work is so paramount. It is the only way that we can begin to seek justice from an unjust system that failed Eastman and Strayhorn.

Q: How has the juxtaposition between Strayhorn and Eastman’s music with your own text helped you navigate potential similarities between the two?

JB: It’s been an interesting journey to study these two men and their life stories. In doing so, I have found that there is very little that has changed in terms of how society views Black queer men of color. Speaking for myself, I still feel that Eastman’s radical approach to reform is still necessary in order to gain the attention from those who make the decisions about what gets programmed in American classical music, even today. There are many more like Strayhorn who have worked in near obscurity.

There is a lot that resonates within their personal lives and my own. I’ll share more on that in the recital. As for the similarities, in spite of the very challenging yet fulfilling lives they lead, they created masterpieces. I resonate so much with this and aspire to do the same.

Billy Strayhorn with Duke Ellington. Photo Credit: David Redfern / Getty Images

Q: There are also interesting contrasts. With both Eastman and Strayhorn, recognition for their contribution to American music came late but for different reasons. Strayhorn was often overshadowed by his close association with Duke Ellington, seen as the ‘silent composing partner’ in the background of Ellington’s sweeping popularization of Jazz. The contrast with Eastman is interesting; whereas Strayhorn’s music received widespread appreciation even though his role in producing it was not widely known in his lifetime, Eastman lived a more theatrical public life of performance and provocation and yet his music was almost forgotten. How do these contrasts in public/private persona inform your thoughts about each composer or your ideas about their music?

JB: Eastman’s music is very bold, much like his personality. People say that he was a bold person. While Strayhorn’s music is laden with themes of suppressed desire for romance, a longing for yesteryear. Granted, he was from an earlier time period where the punishment was much greater for practicing homosexuality, and opportunities for colored men in general were few and far between. I wonder how bold he would have been if he were working in a more progressive time period like Eastman. I do want to note that both artists were working and living in very important cultural shifts in this country.

I think both personas represent two very important aspects of what it means to be a queer person of color working in show business. You are either like Strayhorn, toiling in the background, reinventing the wheel, curating American culture as we know it. Or you could be unapologetically queer and black in the forefront and be made a martyr for it, like Eastman.

There is within both of their works, a great range of emotion that goes beyond what I’m presenting within this recital, of course. Eastman’s “Stay On It” comes to mind, it’s very hopeful and electric. With Strayhorn, I will say that it was a challenge to find vocal music that wasn’t a little melancholy. A lot of his vocal music is about love lost, but that could have just been the popular style at the time, and remains to be a common song writing theme. In a way his music remains incredibly relevant—there will always be heartbreak. After sitting with his music for some time, I really got the sense that he was a man who was always yearning for something more. I resonate with this. Strayhorn has a wide range as well to be very clear, he wrote musicals, operas, and of course swinging tunes like “Satin Doll” and “Take The A Train.”

This is what inspired the idea for me to share short stories inspired by my love life. I thought it would be an interesting way to advance the form. In my experience, I have not observed the marriage of jazz and queer short stories in this way.

Q: Aaron, both Strayhorn and Eastman’s music seem to offer different potential for improvisation. The Eastman scores seem especially challenging; much of his music is laid out as sketches of melodic material, with a lot of space for the performer to interpret the direction, duration, and overall shape of the music. How have you navigated that as a solo pianist interpreting pieces that were intended for multiple instruments?

AD: Essentially, I try to absorb the sound world of the compositions as they were originally intended, and from there try to capture the themes, textures, and overall feeling of the piece in a solo piano reduction.

Q: Let’s talk about Eastman’s role as provocateur. Two pieces on the program have deliberately provocative and deeply offensive titles. These titles appear to (on the surface) have little to no relationship with the music itself which seems to maintain a conscious abstraction from the meaning and implication of words. The Eastman works on the program are also all instrumental, so they provide no explanation in musical terms. Are these titles Eastman’s way of creating what Roland Barthes called “the bait of meaning”? How do you interpret or rationalize the composer’s intentions here?

JB: I think this question is very important. Eastman definitely meant for this title to be inflammatory. David Borden quotes Eastman in “Gay Guerrilla” by Packer and Leach, as the n-word being “that which is fundamental.” It’s funny to think that this piece was written in 1979 and remains equally controversial today. I think that while the title is uncomfortable, it celebrates Eastman at his most brilliant state. In choosing to title his compositions with the n-word, he forces audiences to come face to face with our irrational hatred, thus make way for healing.

Even today, there are very few composers who would dare challenge the administrators in classical music, by writing pieces such as “Evil N.” Although his approach is often provocative and unflinching, I believe this is the sort of bravado needed in order to bring true reform to American classical music today. Even today his work alarms people, it makes them sit up straight, really pay attention, and spark a dialogue. His compositions require us to consider the woman, the negro, the “gay guerrilla” – a term he coined, meaning someone who is someone who is sacrificing themselves for a point of view.

“Gay Guerrilla” for example inspired me to take a radial, almost extremist approach to writing my own opera libretti. To me, his approach, while sometimes shocking, lude or crass, is highly effective. I personally like to compare him to the “Malcolm X” of composers.

Q: What do you hope audiences walk away with after this concert?

JB: I hope audiences walk away from this with a few things, including:

- A deep sense of reverence for the legacy these two artists.

- A sense of urgency.

- Curiosity in terms of finding new ways to extend the lineage of these two men.

- Insight into the black queer sensibility.

- I hope they walk away enlightened.

Eastman once said that he hated Louis Armstrong but he loved John Coltrane, he felt that Coltrane was the one to say “I’m not here to entertain you. I’m playing this for myself.” I hope they get a sense of this energy.

Joshua Banbury and Aaron Diehl perform at The Phillips Collection on January 15. To purchase livestream tickets, visit: https://www.phillipscollection.org/event/2023-01-15-aaron-diehl-and-joshua-banbury

Questions: Jeremy Ney & Thomas Hunter