With students out of school, some families may have more time to slow down, reconnect, and enjoy their long summer days. We hope to see you around the Phillips this summer (check out upcoming events), but you can always bring The Phillips Collection into your home through creative art-making activities for artists of all ages. Tune in to the blog over the next several weeks for the Phillips-at-Home Summer Series to learn more about artists in our collection and discover new ways to make their artworks come to life.

Our first project of the series features the artist Heinrich Campendonk. Campendonk’s painting Village Street currently hangs in the Phillips’s family’s former dining room. For this art activity, you will create a collage-style painting inspired by your environment and your community—just like Heinrich Campendonk.

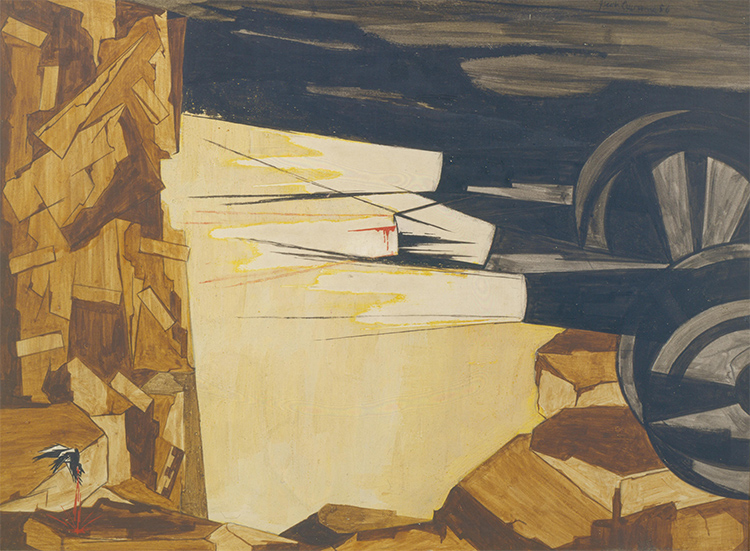

Heinrich Campendonk, Village Street, 1919, Oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 26 3/4 in. Gift from the estate of Katherine S. Dreier, 1953. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Look closely: What do you see in this painting? What colors do you see and how do they make you feel? Do you think this painting looks realistic? Why or why not? How does Campendonk create a collage-like effect in this painting?

About the artist: Heinrich Campendonk was born in Krefeld, Germany on November 3, 1889. While he was working on this painting (1916-1922), Campendonk was living in Seeshaupt, Bavaria. (Bavaria is a state in southeastern Germany bordering Liechtenstein, Austria and the Czech Republic.)

Campendonk used many Bavarian elements in this painting, such as a church, spotted cows, lean-to sheds, spruce trees and wooden fences. All of these elements represent Campendonk’s community to the viewer. He used luminous colors such as red, blue, brown—can you see how these colors appear to rise out from the dark background? In keeping with Campendonk’s technique, our first project encourages you to get outside, explore your neighborhood, and create a picture that artistically shows your observations.

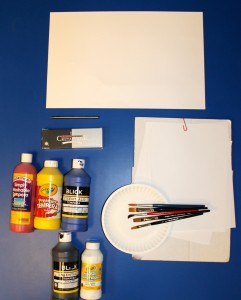

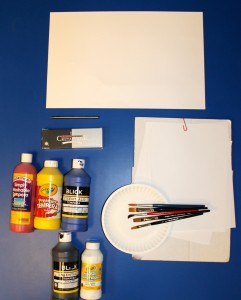

WHAT YOU NEED:

Materials needed

- Plain white paper

- Graphite pencils

- 12” x 20” paper for final project (larger than 8.5 x 11’’ encouraged. Canvas is optional)

- Red, yellow, blue (Primary colors) and black & white tempera paint (has a faster dry time)

- Paper plate palette for paint

- A couple of paint brushes (markers optional)

- Scissors

SUGGESTED AGE:

*See optional project modification for younger age groups*

TIME FRAME:

- Full-day activity (6-8 hours)

STEPS:

1. Go on a walk in your neighborhood. Bring a sketchpad to record your observations. What makes your neighborhood special? What are some of its identifying characteristics?

Exploring around the Phillips Collection and Dupont Circle, Photo: Julia Kron

2. Do at least one sketch of each of the following:

- Your house

- Your street

- One building in your area

- An animal or plant

- A detail that you consider important to your neighborhood

Once you are happy with your observations, return back to an art-making space to begin the final project.

3. Look through your sketches and select at least 5 observations for your final painting. Cut them out.

Step 3 Example, Drawing: Hayley Prihoda

4. Arrange the cut-outs on your larger piece of paper, move them around like a puzzle, thinking about a background, middleground and foreground in your composition. Campendonk’s composition is arranged like a collage; feel free to overlap your sketches, use geometric shapes and lines, and play around with the scale and arrangement of your objects.

Step 4 Example, Drawing: Hayley Prihoda

5. If you would like to alter the scale of your sketches, you may choose to re-draw them on your larger paper. Otherwise, go ahead and glue down your sketches onto the paper. Heinrich Campendonk frequently used geometric shapes and symbols to represent his surroundings and you can do the same!

6. When you are ready to begin painting, select a few colors that encapsulate your experience in your neighborhood. As a member of the Blaue Reiter group, Heinrich Campendonk was highly impacted by color and used color to represent his emotions and sensations, rather than the reality of his surroundings. Because of this, his paintings often have a dream-like appearance.

7. Start painting your background layer first and work your way to the foreground. Make sure to take your time painting, allowing each layer to dry to maintain your colors.

8. You have created a beautiful painting! Please leave a comment or share a picture of your creation with the Phillips on Twitter (@PhillipsMuseum).

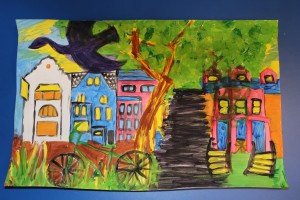

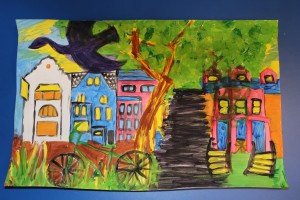

Final Example #1 for 10 and up audience, done with tempera paint, Painting: Hayley Prihoda

Final Example #2 for 10 and up audience, done with tempera paint, Painting: Julia Kron

*For younger audiences, focus on shapes, colors, and symbols during your walk. Sketch five different objects around the community (your house, a building, a plant or animal, your street, and other details). Use markers to color the sketches and then cut them out. Paste sketches onto larger paper using a glue stick. Add additional colors as desired.

Final Example for younger audience, done with markers, Drawing: Julia Kron

Tune in regularly for more great art activities inspired by The Phillips Collection!

Hayley Prihoda and Julia Kron, K12 Education Interns