Alma Thomas taught art at Shaw Junior High School for 35 years. She said: “I devoted my life to children and they loved me.” To honor and connect to Thomas’s career as a teacher, we asked DC-area educators to respond to works of art in Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful . These educators participated in the Phillips’s 2021 Summer Teacher Institute, exploring ways to adapt arts-integrated lessons to their students. Read their perspectives on how they personally connected to Thomas’s artworks.

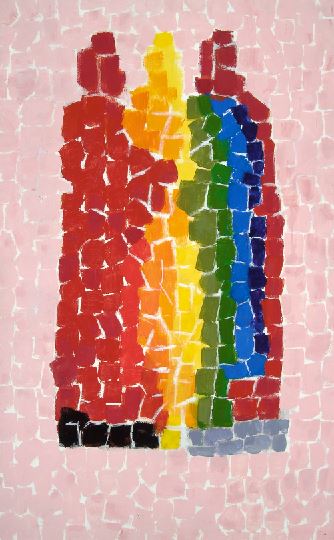

Alma W. Thomas, Three Wise Men, 1966, Acrylic on canvas, 36 1/2 x 23 1/2 in., The Harmon and Harriet Kelley Foundation for the Arts

Gratitude. Purpose. Learning. These are the three most valuable points that resonate in me when I look at this painting. The wise men are the carrier of three beautiful gifts.

Gratitude. As I wake up each day, there are so many things that I am thankful for. Foremost, is the gift of LIFE, especially during these tragic times when many people all over the world are dying.

Purpose. In 2015, I had a major car accident while I was seven weeks pregnant. Miraculously, I did not have a single bruise or cut. Since then my purpose of having a second life is making people know that there’s an omnipotent power above us. That experience led me to prioritize making great memories with my family and friends.

Learning. Knowing that this world is so vast and limitless gives us the chance to explore and learn. In this lifetime, it is important to embrace our own beauty, develop our courage, enhance our relationships, and live our life with passion.

What are you hoping to gain from the three wise men?

—Irene De Leon, Service Coordinator / Early Childhood Special Educator, Judy P. Hoyer Early Childhood Center

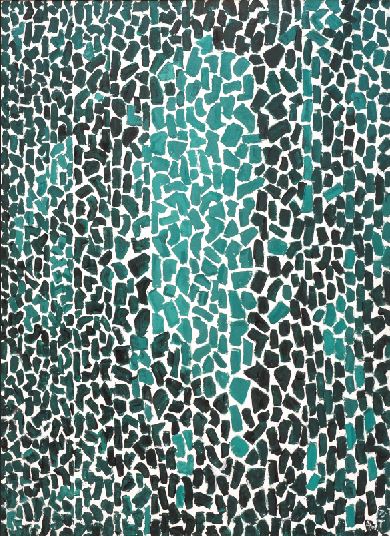

Alma W. Thomas, Wind Sparkling Dew and Green Grass, 1973, Acrylic on canvas, 69 x 50 in., Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Indiana, Gift of Vincent Melzac, 1976.04

This expressionist abstract painting about nature connects us to a feeling of calm and peacefulness. “Sparkling dew” recalls memories of walking across a dew-filled morning lawn, while “wind” associates memories of raindrops running down a window pane. Irregular dabs of blues and greens further add to the qualities of tranquility. An educator by profession, Alma Thomas developed her iconic style in the 1960s, at the age of 69. She was fascinated by her observations of shifting light in her garden. She was also influenced by Claude Monet’s paintings. In her own words, her artwork was meant to evoke “the heavens and stars.” Thomas serves as an inspiring role model, reminding us that educators who are also artists can do both, and thrive, in any stage of life.

—Eileen Cave, Grades PK-6, Visual Art & Arts Integration Lead Teacher, Rosa L. Parks Elementary School