The Phillips is hosting a book club about Latinx Art by Arlene Dávila on January 21. Fabiola R. Delgado (she/her), a Venezuelan Human Rights Lawyer turned independent curator, creative consultant, and programs specialist, who will be leading the discussion, shares some insights about the book.

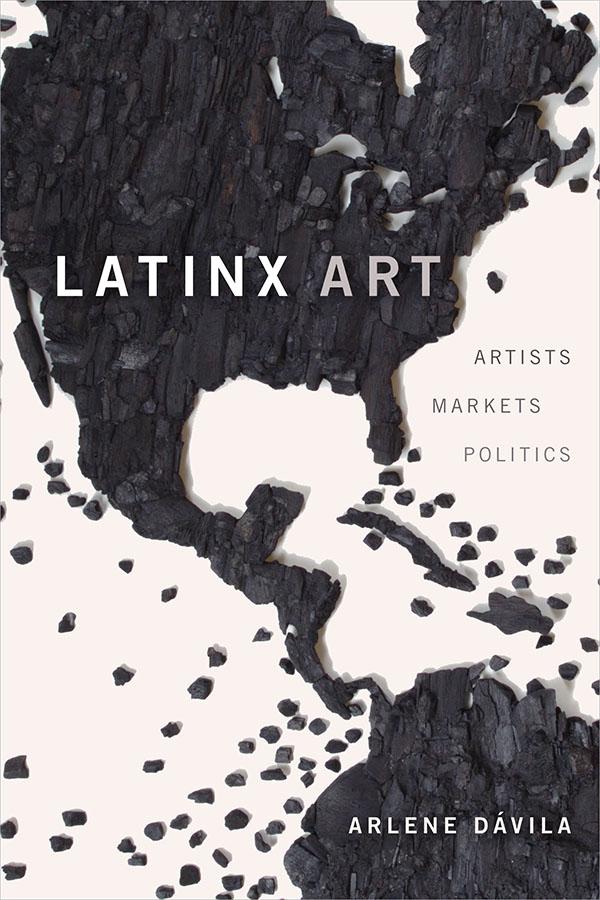

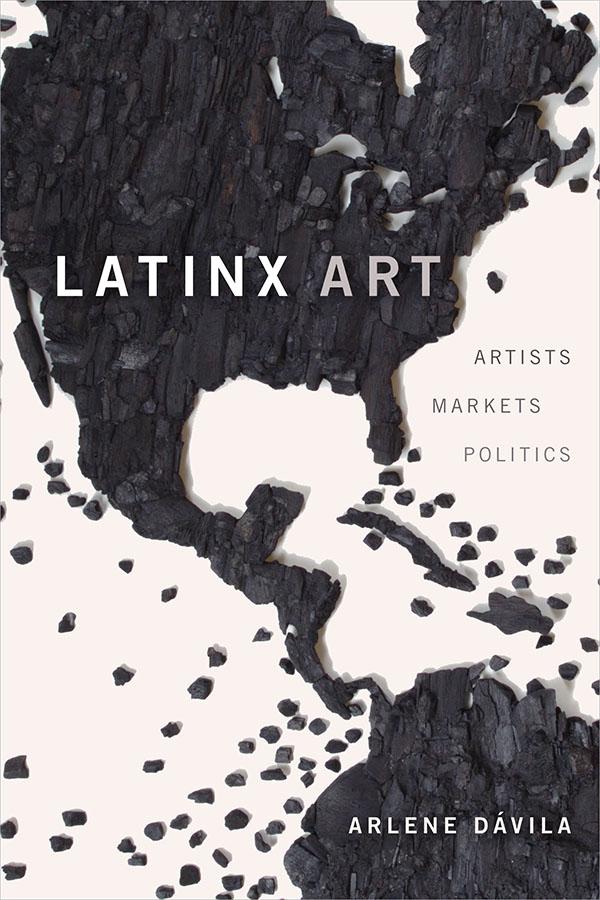

Latinx Art

When first introduced to the book Latinx Art: Artists, Markets, and Politics by cultural anthropologist and NYU Professor Arlene Dávila, I was eager to know how she defined the term “Latinx” and most specifically the concept of “Latinx art.” While the US American neologism “Latinx” rose in the mid 2000s as a gender-inclusive noun (replacing the binary and genderized Castilian grammatic Latino/Latina), the multivarious nature of what historically has been called a single cultural/ethnic group: Hispanics/Latinos, and the different experiences of those groups in the United States, have prevented the term from reaching its collective identity status outside of academia and cultural influencer circles. In these spaces, Latinx refers to a person of Latin American descent based in the USA (whether immigrant, first, or higher generations), separate from Latin Americans. This is the main distinction to consider when reading the book, because it anchors the author’s perspective through her introduced concept of “national privilege” (a direct connection to Latin American territory). Equally important is the need to read this through a multifocal lens: it’s not about setting one group against another, but recognizing and accusing the race and class disparities evidently displayed in the art world, that position white work as the natural category, and anything other than white as an accessory.

The issue of the art market (amusingly described as the largest informal economy for its lack of transparency and monitoring) favoring art that’s identifiable within the canon of art history, is raised along the claims by some that Latinx art has no specific nationality, geographic location, or visual recognizable characteristics; and though I accept there’s no typical look to what Latinx art is, I press on the first two claims and ask: Is Latinx art not made in America? Is it not American? These positions raise conflicting views of a desire for an art market that’s “separate but equal” or fully integrated. I cannot provide a definite answer, but until we refute the normalization of “American” as white, and contest the “American Art” and “Contemporary Art” identifiers (I would add “Old Masters” to the list), we’ll continue to contemplate and theorize exchanges that only offer initial arguments to dismantle the racist status-quo of the global art market, and instead can motivate the otherization of parallel markets: Black Art, Indigenous Art, Asian Art, Caribbean Art, Latin American Art, and maybe eventually Latinx Art.

The author is clear when she states that Latinx art is a culture making project, rather than a fixed identity, acknowledging the work of artists excluded from both US American and Latin American art history, and reminding us of the permanent state of flux in which Latinx people are perceived (“ni de aquí ni de allá”) in tandem with the riddling case of marketable ethnicity. For this reason, many researchers that explore the art world (or worlds?), art education, image, and identity, including Dávila, refer back to the words of ethnologist Fred Myers: “To imagine conditions of cultural heterogeneity, rather than those of consensus, as the common situation of cultural interpretation.” It is difficult to find any conclusive statement, but I invite readers to continue questioning what’s considered the norm and push for policy changes that will ultimately resound in the collective culture.

In sum, “Identity” is in. “Identifiers,” still a work in progress.

Fabiola R. Delgado (she/her) (@call.me.fa.) pursues justice through art and cultural practice, striving for thought-provoking projects that bring forward different perspectives and encourage intergenerational creative learning, after her activism in Venezuela proved too dangerous, forcing her to move to the United States where she currently seeks political asylum. Fabiola has worked with various Smithsonian Institution museums including the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the National Museum of Asian Art, and the National Museum of American History, the Embassy of Spain, Times Square Arts, Washington Project for the Arts, Latela Curatorial, No Kings Collective, the Center for Book Arts NYC, The Fundred Project along MacArthur Fellow Mel Chin, and the Obama White House.