On October 15, The Phillips Collection will be reopening some galleries to the public, after being closed since March due to the covid-19 pandemic. Director of Strategy and Operations Micha Winkler Thomas and Security Operations Manager Bob Harris share the months-long process of welcoming staff and visitors back to the museum.

Who did you work with on the reopening process?

Micha Winkler Thomas: The reopening process has been a months-long collaborative effort, starting in May when we formed a Reopening Task Force consisting of colleagues from every department. This dedicated team met weekly, gathering and analyzing information to determine how and when The Phillips Collection would reopen. This included following the Mayor’s Reopen DC guidelines for a phased reopening of cultural institutions, CDC health recommendations, looking at the current data for DC, as well as reaching out to health expert Joshua Sharfstein, current Vice Dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. We conferred with national and international museum colleagues who either reopened or were in the process of reopening to gain best practices and lessons learned, using their admissions statistics to determine our best plan of action.

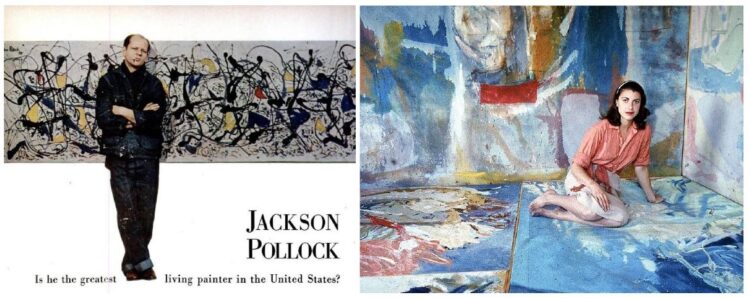

Reopening Task Force members in the galleries in September conducting one of many rounds of beta testing of the visitor experience to make sure it is safe and enjoyable.

How did you tackle the development of a plan?

MWT: The key to our reopening plan was our careful and deliberate phased approach. The state of the pandemic is so uncertain, so it is important for us to remain flexible. By beginning our reopening with only the Goh Annex and Sant Building on a limited basis and for a limited number of guests, we are hoping to create a serene and safe haven for our guests and staff to experience the amazing art of The Phillips Collection. We will open the House galleries and add more timed entries based on DC and CDC health guidelines, and also when we feel the time is right.

Bob Harris in the galleries determining the best route for visitors.

How has the building and art been kept safe over these last few months?

Bob Harris: Our security staff has been on site through the entire closure, and we are very thankful to those heroic, dedicated, and exceptional staff members that kept our buildings and artworks secure for so many months. We carried out the 24/7 security functions and tasks to protect the offices and galleries. I joined the Phillips in May, leaving the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts after nearly a decade in their Department of Security Services. In fact, I have been in law enforcement and security for nearly 40 years and have become a subject matter specialist on museum and cultural property protection principles and methodology. As a commander, I was involved in helping to conduct the closure at the VMFA in March, and I brought my expertise to the Phillips.

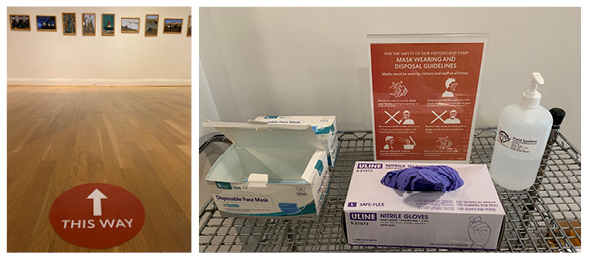

Contactless temperature check stations at staff and public entrances, and hand sanitizer stations throughout the building.

What has been done to ensure the safety of staff and visitors?

BH: Every safety measure we have put in place has been to protect both our staff and visitors—it is important that our staff is subject to the same protocols and considerations as our guests. We conducted an anonymous staff survey to determine what everyone would be comfortable with and what people were concerned about. We have worked closely with our facilities team to optimize our air filtration throughout the building. The summer months focused on enhanced onsite safety protocols for returning staff as well as preparing for the museum’s reopening. PPE stations, hand sanitizer stations, and safety signs were put in place throughout the museum, along with covid-19 return to work staff and visitor protocols to ensure social distancing and mask adherence. Contactless temperature/mask readers were installed at staff and public entrances, as well as Plexiglas partitions at the reception desk, admissions lobby, and museum shop. We measured every gallery to determine capacity in every space and on each floor, carefully determining the best route for visitors and to minimize crowding and cross traffic. The team has created a directional visitor flow plan that will allow for social distancing as well as an engaging visitor experience upon the museum’s public reopening. Security staff have been brought back in a phased approach to meet reopening operational needs. While we still have a lot to do to fully reopen, I am proud of our hard work across departments that has made reopening possible and we are thrilled to finally welcome visitors back in the galleries to enjoy the art!

Signage and PPE stations placed in galleries and office spaces.