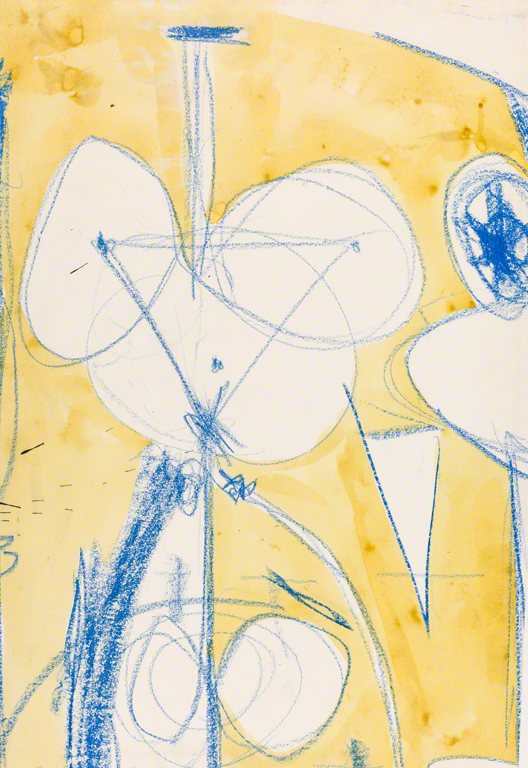

Theodoros Stamos, The Sacrifice of Kronos, No. 2, 1948, Oil on hardboard, 48 x 36 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1949 © Estate of Theodoros Stamos, New York

Sacrifice of Kronos, No. 2 by Theodoros Stamos, along with his Sacrifice of Kronos and Saga of Ancient Alphabets (all on view in Ten Americans), allude to the interconnected realms of nature, myth, and ancient culture that figure prominently in Stamos’s art. Based on a Greek myth, Sacrifice of Kronos is inspired by the dramatic story of Kronos, king of the Titans, who consumes his children to prevent the fulfillment of a prophesy that one of them will grow up to usurp his throne. When his wife wraps a stone in clothing to fool Kronos into thinking it was their newborn son Zeus, Titan consumes the stone. Rather than showing the eventual fate of Titan dethroned by Zeus, Stamos evokes the moment of sacrifice with the presence of a fetal-like form trapped under the weight of the massive boulder. While more commanding in scale than works by Klee, Stamos’s painting, with its metaphorical allusions to broader themes of birth, death, power, and sacrifice, are reminiscent of Klee’s quest to uncover universal aspects of human experience.

This work is on view in Ten Americans: After Paul Klee through May 6, 2018.