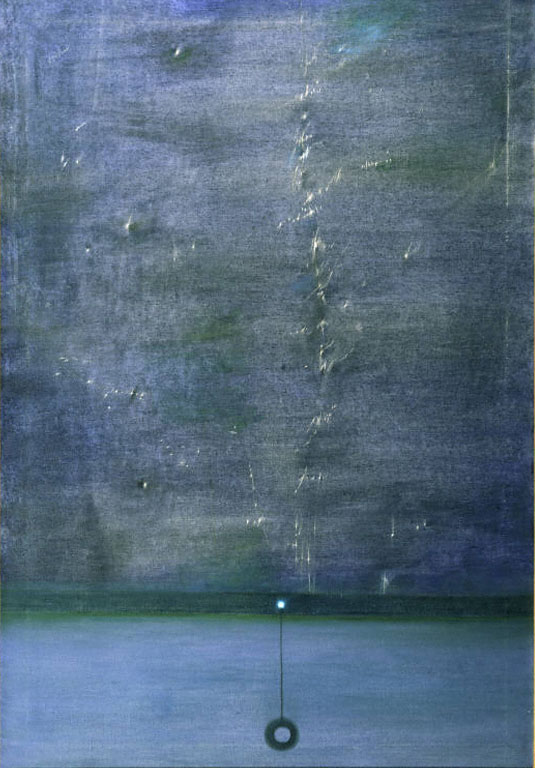

Loren MacIver, The Window Shade, 1948, Oil on canvas 43 x 29 1/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1951

In art, we often think of abstraction and representation as being complete opposites. We think of Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, titled with numbers, as being polar opposites to Paul Cézanne’s still lifes, labeled exactly what they are: apples, oranges, and flowers. But what if something is both abstract and representational? Is it possible? Currently on view is Loren MacIver’s painting, The Window Shade. At first glance, the work appears completely abstract, but upon closer inspection of both the painting and the wall text beside it, we learn that it does in fact represent something from real life: a window shade.

Walking past MacIver’s work, I recognized that I liked the aesthetic, but it didn’t necessarily evoke a specific emotion from me. Circling back, I decided to look at it more closely. When I approach a piece, I tend to ignore the wall text at first and look instead at the surface texture. I liked that the artist applied the grayish blue color very thinly, leaving specks of the canvas showing behind it. To me, that reveals more of the process, which is something I like to be aware of when studying a work of art. Scanning the painting, I then noticed a recognizable object in the bottom fourth of the canvas: a string hanging down with a hollow circular pendant attached. I wondered why this would be there given the abstract nature of the work. It was only then that I turned to the title, The Window Shade. Suddenly, the piece had so much more meaning for me. I began to think of the specks of untouched canvas as illumination from street lamps coming through the rips of a worn piece of fabric. The slightly different hue in the bottom quarter of the canvas, separated by a darker border, became the color of twilight filtered by the glass on top of it. These are conclusions I would not have come up with had I not stopped to read the wall text beside the piece and inspect it more closely.

So what is in a title? A title can help us pull meaning from a seemingly non-representational work of art. It can turn thinly painted canvases, almost monochromatic in nature, into old window shades, evoking a sense of nostalgia for a passing day.

Annie Dolan, Marketing and Communications Intern