Read the other posts in this series here.

On day three of our celebration of FotoWeekDC, we look at the enigmatically beautiful photography of artist Francesca Woodman on display in Shaping a Modern Identity: Portraits from the Joseph and Charlotte Lichtenberg Collection.

Francesca Woodman first began her experiments with photography at the age of 15. Two years later, as a student at Rhode Island School of Design, she continued her exploration of black and white photography and film until she took her own life at the young age of 22. Despite her short lifespan, Woodman was prolific, creating over 10,000 negatives in just 7 years.

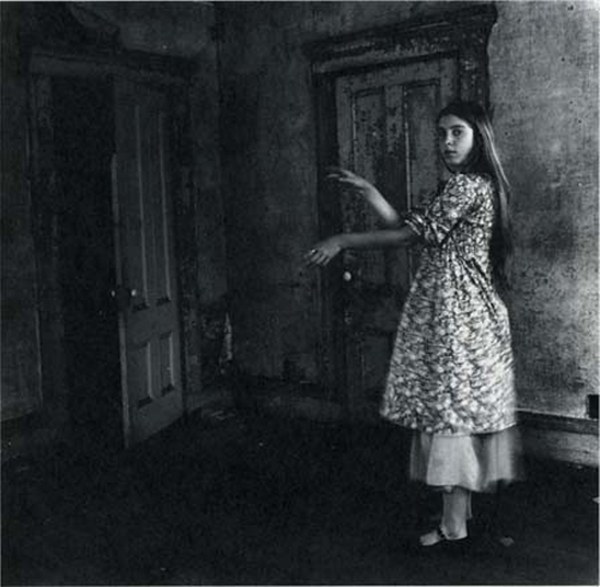

Francesca Woodman, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975-76, Gelatin silver print. Courtesy George and Betty Woodman.

Woodman’s Providence, Rhode Island is one of only two self-portraits in the installation. While Harry Callahan’s portrait of his wife Eleanor strove to achieve formal autonomy without an introspective look into his subject matter, Providence is an exploration of Woodman’s inner psyche. She perpetually looked to herself as the subject of her own works, using her body to convey her inner emotions and thoughts. Her admiration for the fashion photographer Deborah Turbeville shows in the lushly shadowed and textured scenes Woodman shot in an abandoned house in Providence, Rhode Island, where her own figure often blurs into a ghostly, dematerialized form. In Providence, Woodman navigates both past and present; she appears in prairie-style dress and shoots with medium-format film reminiscent of the turn-of-the-century, yet her disposition is urgent, contemporary. The camera captures her in the dilapidated interior in the midst of movement (seen in the blurred lines of the hem of her dress and her arms) with her arms eerily extended towards the doorway as she stares out at the viewer. The open door suggests a way out of this transient space, but it is unclear if the artist is willing to leave and whether or not her arms are beckoning the door open or closed. This early photograph demonstrates the performative quality of Woodman’s photo and video oeuvre in which the artist engages with her space, using her body to explore the environment around her as well as her internal state.