Phillips Museum Educator Carla Freyvogel spoke with artist Peter Lister, whose work Music Room is in the Phillips’s collection. In 2022, the artist gifted the related print Approaching Music to the Phillips.

In January 2022, the Phillips’s virtual Guided Meditation sessions were inspired by artworks in the collection related to music. On January 5 we highlighted artist Peter Lister and his monoprint Music Room. Lister himself joined our meditation session that day and I interviewed him a few days later.

For those of us lucky enough to work at the Phillips, the title of Lister’s work has a lovely connotation, evoking our magical Music Room in the original Phillips House, a space that reverberates with beauty even when silent.

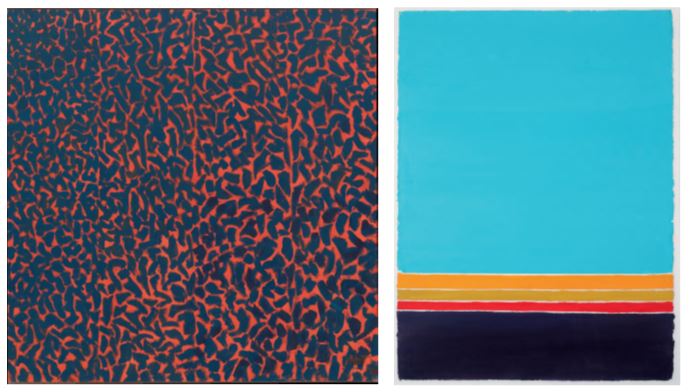

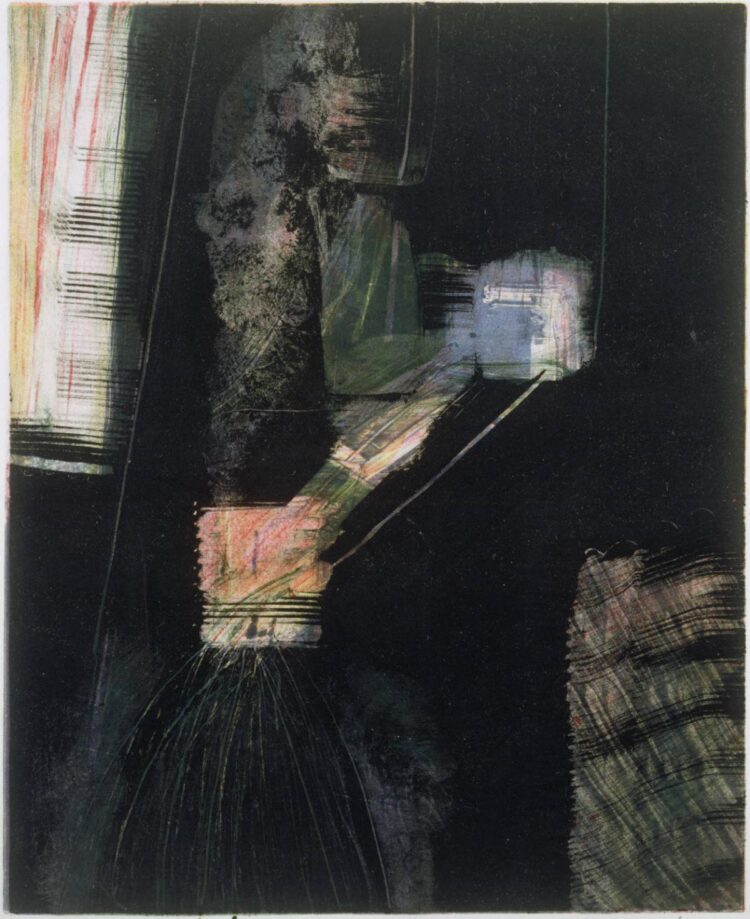

Music Room by Peter Lister is a dark piece, or appears to be at first glance. Then the eye settles on an almost luminous reddish rectangle and travels diagonally to an almost blue rectangle of a similar size. Competing for our attention is a white shape occupying the upper left corner that is scored (scored!) with black lines. Diagonally across, the right corner of the image is anchored by a less bold whiteish shape.

Peter Lister, Music Room, 1976, Color monoprint, 11 x 9 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1967

We discussed the artwork during the meditation session. Some of the participants perceived the presence of a person, perhaps someone who had fingers resting on a string instrument, getting ready to strum or do a bit of pizzicato? Others identified a blurred musical score in the upper left while some interpreted this area as a window with a scrim or a curtain in red and yellow stripes.

Music Room was created in 1976, when Lister was 43 years old. It was purchased by The Phillips Collection’s then chief curator, James McLaughlin, from Philadelphia dealer Robert Carlen. Carlen is known for promoting the work of Horace Pippin. I had a chance to chat with Lister about his Music Room, how it came to be in our collection, and how his practice has evolved over the years.

Peter Lister is a native to the Philadelphia area. A 1958 graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), he was the recipient of two fellowships that allowed extensive study abroad. While now he works in watercolor and watercolor pencil, most of his early career was defined by oil and acrylic painting and printmaking. He also taught studio art at Rosemont College.

The travel fellowships exposed a world of beauty and artistic inspiration to Lister. Greece captured his heart. Here is an example from c. 1980. Inspired by a famed church in Mykonos, Lister started to create several casual works he called “fantasias.” He described trepidation in beginning this series: “When I got there I was absolutely frozen with fear that I would not know what to do or how to do anything. So I started at the edge of the paper…with a kind of strip of the color, and trying things out and then made my way boldly into the paper.”

Peter Lister, Fantasia (Mykonos), c. 1980, Acrylic on paper, 9 x 12 in., Collection of the artist

Ultimately, this church proved to be one of his most successful subjects. He sold most of the 60 or 70 pieces he produced in this series. He reflected on the church and surrounding scene and remarked: “I had fun with the steps…I looked at this and I said ‘You were cleverer than you knew, Peter.’ I love the rhythm between the four steps, three steps. That’s music too”.

Lister’s oil painting from 1959, Firemen, was included in an exhibition at PAFA in 2017 called The Loaded Brush: The Oil Sketch and the Philadelphia School of Painting. The exhibition explored the legacy of Thomas Eakins. Eakins’s firmly believed that by sketching in oil, an artist would be able to authentically capture the fleeting experience of light and gesture.

Peter Lister, Firemen (Gladiators), 1959, Oil on canvas, 12 x 16 in., Collection of Bill Scott, Philadelphia

When comparing Firemen from 1959 to the Fantasia painting of the church in Greece from 1980, we can see that spontaneity continued to be important to Lister throughout his career. He uses thick impasto for the church walls, with some forms appearing to float and the blending of white becoming almost gray.

I was curious about his recurring references to music, both in Music Room and in his perception of the rhythm of the steps in Fantasia.

Lister became infatuated with music at a young age. He said, “I think part of my fascination with music was the printed note. That it made the music happen in the sense that I was looking at a visual image, a script, writing, and I was able to interpret it into sound….and the fact that the notes on the page could be transformed into sound. It became just fascinating to me.”

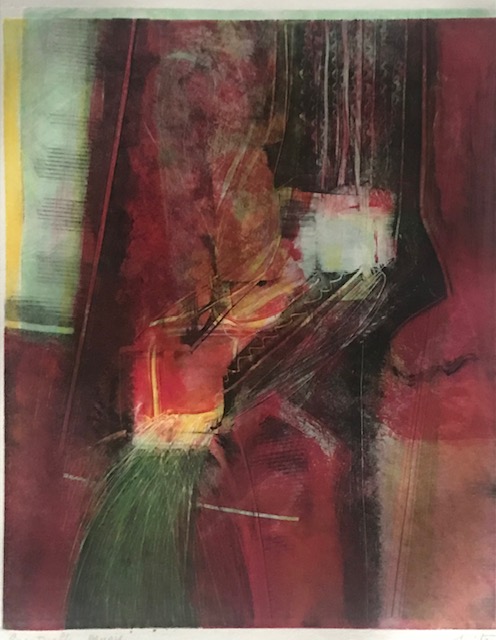

Lister kindly shared with me an image related to Music Room. Titled Approaching Music, it is the first pull from the plate that produced the monoprint Music Room, and Lister recently gifted the work to the Phillips. The plate was zinc and once had a life as an etching plate. Why Approaching Music? I asked. “It wasn’t quite music yet because the tension between the triangles is murky at best…”

Peter Lister, Approaching Music, 1976, Color monoprint, 14 1/8 x 9 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of the artist 2022

In both images, the whiteish rectangle in the upper left corner pulls our eye. In our meditation group, some participants saw a page of music, others saw a window. Lister said, “So many painters have that inside-outside use of a rectangle. Certainly Matisse—it is just everywhere in his work. Picasso, those major French painters. Think of the American Impressionists; they always seem to put their wife or daughter in front of a window and paint her there.”

“We live inside and we look out. I don’t set out to put a window—a window opens. When I am in a landscape, there isn’t a window, I am looking out because I am in.” He explained that as he works on a piece, an abstract image often becomes more realistic. A large pale area might evolve from being a compositional device to being an actual window.

Through our conversation, Peter Lister opened a window onto his world and his work. I want to extend a huge thank you and much warm gratitude to a talented artist who took the time to talk with me and to share his process and art with our meditation community.