Milton Avery, Dancing Trees, 1960. Oil on canvas, 52 x 66 in. Paul G. Allen Family Collection © 2015 Milton Avery Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In his mid-seventies, Milton Avery brought decades of visual experience to bear on his perceptions of the world and an inclination toward simplification that may have intensified with his advancing age. At times, the artist’s late paintings veer so close to pure abstraction that only their titles enable the viewer to recognize the scene that has stirred Avery’s imagination. Such is the case here: three monumental cones swaying in the wind take flight as trees en pointe, their girth making for a comic ballet.

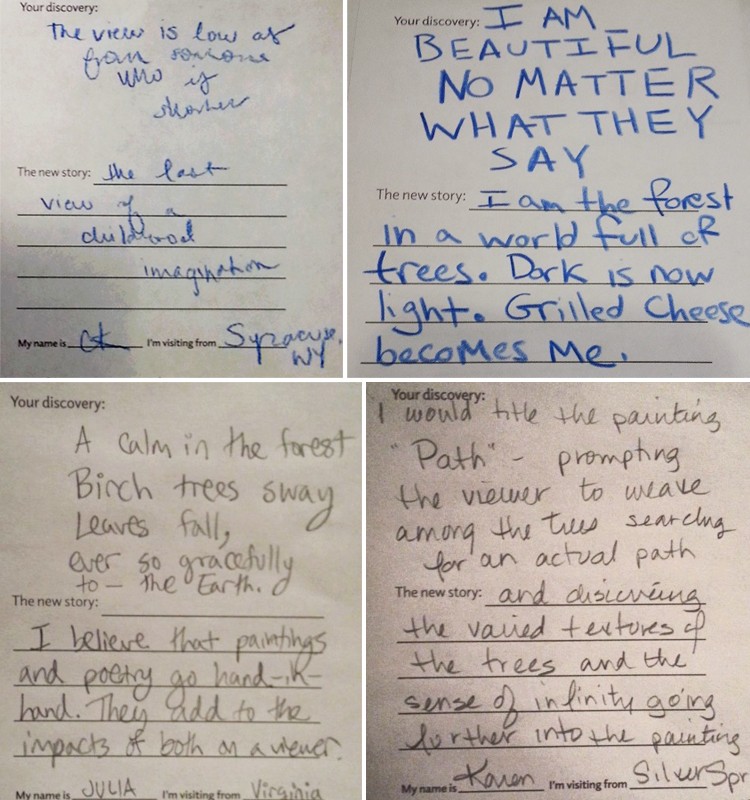

A few weeks ago, prompted by a free-writing exercise based around this piece, we asked visitors to Seeing Nature and social media followers what they saw in this work without providing the title. Answers included floating pizza slices, icebergs, a gnome village, stingrays, and more. What do you see?