Duncan Phillips once explained “I bring together congenial spirits among the artists from different parts of the world and from different periods of time.” Phillips’s curatorial philosophy is a hallmark of The Phillips Collection and gives visitors the opportunity to see artworks from different time periods, originating from different countries, created by different artists displayed together under one roof. Displaying artworks in this way allows visitors to discover new relationships between familiar artworks.

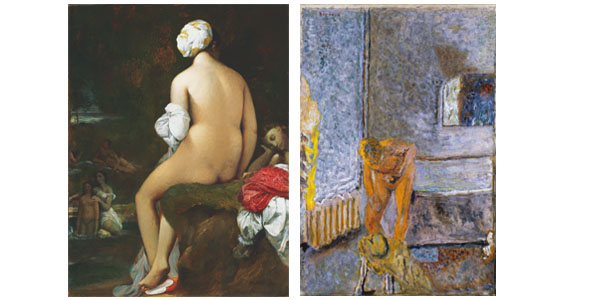

(left) Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Small Bather, 1826. Oil on canvas, 12 7/8 x 9 7/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1948.(right) Pierre Bonnard, Nude in an Interior, c. 1935. Oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 19 3/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1952.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s The Small Bather (1826) and Pierre Bonnard’s Nude in an Interior (c. 1935) provided such a point of departure for one of my recent tours of special exhibition Snapshot: Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard. As I did visitors on my tour, I invite you to consider the relationship between these two artworks, and ask yourself the following set of questions:

What do you see in each work of art?

What is the subject?

How would you describe the style of each painting?

Next, consider additional question:

What are some similarities and differences in both the style and subject of these two artworks?

And finally, ask yourself:

How might the invention of the camera inspire some of the differences between the two artworks?

I encourage you to share your observations in the comment section below. You can read some responses I received on my tour after the jump. Continue reading