Sunday Concerts, the Phillips’s time honored music series, began in 1941. Before then music had always been a part of life at the museum, but the formal inauguration of the series aimed to bring the same level of ambition and experimentation that Duncan Phillips had for the visual arts, to music. The charge was led by the inimitable Elmira Bier, Duncan Phillips’s secretary from 1924 onwards. Phillips could scarcely have found a stronger advocate in Bier, who although not formally trained in music, schooled herself out of necessity across a broad range of artistic areas. Her lack of musical preconceptions may have been her strongest suit, as it led her to take risks, especially in her encouragement of young artists. This remains a central tenet of the concert series today as we carry the torch into the current 73rd season and beyond.

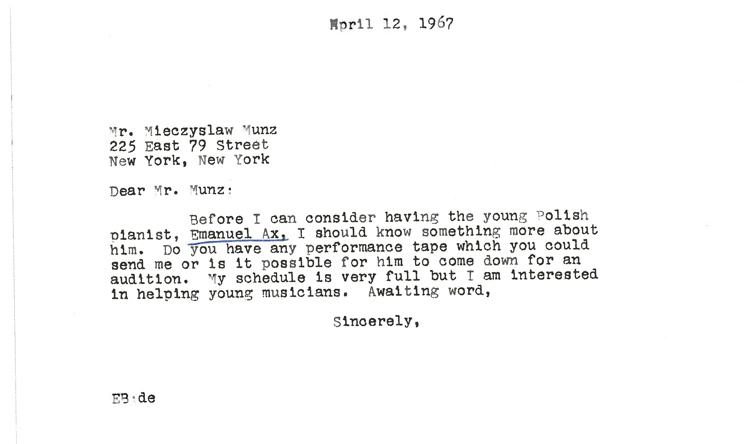

This spirit of openness and support for young artists is wonderfully encapsulated by letters of correspondence from 1967 between Bier, Polish pianist and teacher Mieczyslaw Munz, and his pupil, an eighteen-year-old Emanuel Ax. Fast forward to today and Emanuel Ax is regarded as one of the finest pianist of his generation who has collaborated with many of the major orchestras and conductors. He has won several Grammy Awards for his recordings, and along with a slew of competition wins and honorary doctorates, also teach at the Julliard School in New York. But in 1967, he was a virtually unknown young Polish émigré studying under Munz at Julliard. Munz wrote to Elmira Bier in March 1967 suggesting that she consider Ax for a performance that season, mentioning his extraordinary qualities, and that the late Arthur Rubinstein thought highly of him. Bier wrote back:

Letter from Elmira Bier to Mieczylaw Munz, September 8, 1967. The Phillips Collection Archives, Washington D.C.

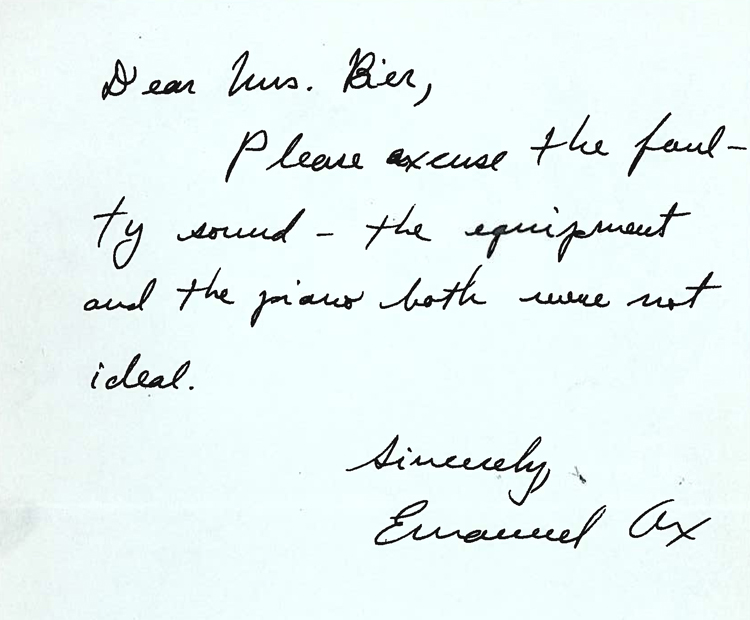

Ax responded and made a recording, sending it to Elmira with a short but revealing disclaimer:

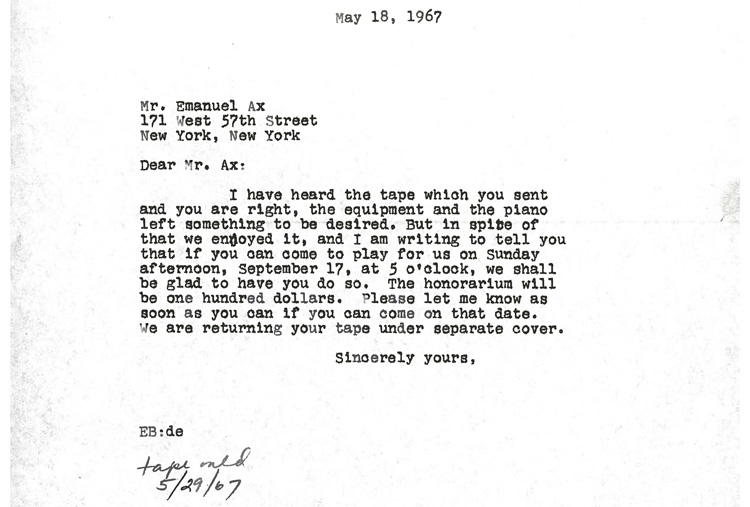

One can imagine Elmira and her staff huddling around an early compact cassette player listening to Ax’s DIY recording. We do not know what he recorded, but clearly it was enough to make an impression on the discerning music director, who wrote back in May of that year offering Ax a Sunday afternoon performance.

Ax wrote back soon after with his ambitious program: two Scarlatti sonatas; the Sonata, Op. 57, Appasionata, by Beethoven; two Liszt transcriptions of songs by Schubert; the Intermezzo in E Major, Op. 116 by Brahms; L’isle Joyeuse by Debussy; and Chopin’s Etude, Op. 10, No. 8 and Ballade in G minor, Op. 23. It was certainly a brave and auspicious choice of works, and shows a musical maturity that belied his young age. He was still a student cutting his teeth on the circuit when he performed at the Phillips, and it is a mystery what the audience would have thought about this young man, who in just 7 years’ time would go on to win the first ever Arthur Rubinstein competition in 1975, catapulting him to international stardom. If they were anything like Elmira Bier, they would have welcomed his ambition and passion for music-making with open arms.

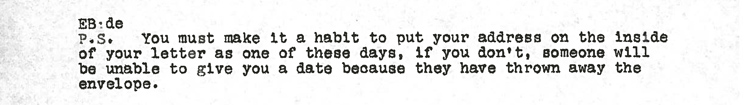

There was one last piece of motherly advice that the worldly wise Elmira had for the young aspiring concert pianist, advice that we are sure did not go unnoticed.

Jeremy Ney, Music Specialist