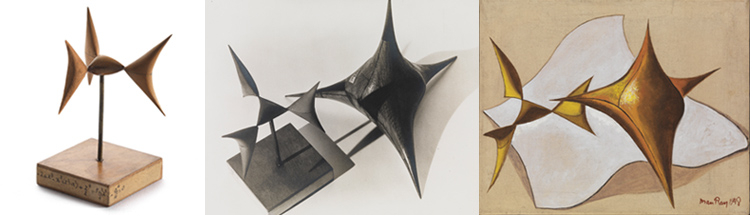

(left) Mathematical Object: Algebraic Surface of Degree 4, c. 1900. Wood, 3 1/8 x 2 3/8 in. Made by Joseph Caron. The Institut Henri Poincaré, Paris, France. Photo: Elie Posner (middle) Man Ray, Mathematical Object, 1934-35. Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. Courtesy of Marion Meyer, Paris. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2015 (right) Man Ray, Shakespearean Equation, All’s Well that Ends Well, 1948. Oil on canvas, 16 x 19 7/8 in. Courtesy of Marion Meyer, Paris. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2015

Defying easy categorization as comedy or tragedy, Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well—with its curious mixture of fairytale logic, gender role reversals, and cynical realism—and Man Ray’s corresponding painting provide a fitting finale to this journey from mathematics to Shakespeare. Removing the wood and metal supports of the mathematical models (seen in the left and middle images above) and placing the untethered forms against an undulating white cloth, Man Ray created a composition in which the objects occupy an ambiguous space between the real and the surreal. These small models find their apotheosis almost a decade later in a 1956 pen-and ink drawing, attesting to the fact that the models he encountered in 1930s Paris continued to haunt and inspire him for years to come. They have gone from three-dimensional objects, once of great utility to mathematicians, into abstract, ethereal forms.

Wendy Grossman, Exhibition Curator