Phillips Educator Carla Freyvogel dives into John Biggers’s painting, on view in African Modernism in America, 1947-67 through January 7, 2024, and connects it to another work in the collection.

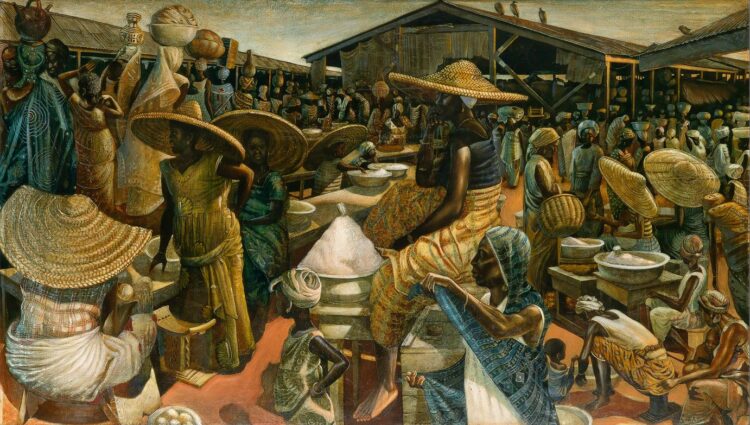

The delight and complexity of John Biggers’s Kumasi Market does not slam upon us at first glance. Rather, it unfolds.

John Biggers, Kumasi Market, 1962, Oil on acrylic on Masonite board, 34 x 60 in., Collection of William O. Perkins III © John T. Biggers Estate / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY / Estate Represented by Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, Courtesy Swann Auction Galleries and American Federation of Arts

Standing at a polite distance, we are met with shades of brown, copper, gray, muted gold, and a few high points of white. But as we approach, multiple shades of blue, ebony, terra cotta, and brilliant yellow emerge along with a hubbub of industrious characters. That is where the delight comes in. Who are all these people? Oh! Some small children! A baby! A plethora of women, strong and busy.

Visitors to African Modernism in America, 1947-67 are intrigued by this painting. I ask them to extend their arms out to each side as far as they can. Yes, your wingspan is no match for the width of this work of art. It is huge. There is much to see.

Installation view of African Modernism in America, 1947-67

How do we absorb a painting as large as this, so full of activity and characters? Biggers helps us: our eyes can hop through the painting by taking in the yellow hats and the brilliant play of sunlight as it catches the weave of the straw. Light bounces off shiny exposed arms and foreheads.

Although the painting is seemingly crammed with a crush of people, consumed with work in their own worlds, Biggers focuses our eyes by containing the scene within the architecture of the market’s warehouses. The wooden beams of the central building’s roofline connect somewhere out of the image, drawing our eyes upward. But Biggers also returns our focus to the foreground, middle-ground, and background by using the linear perspective formed by the adjacent warehouses.

Interestingly, smack in the middle of the foreground, sits an elegant figure, a long-limbed woman, languid and serene. Deep in thought, her chin is absent-mindedly dropped onto the back of her hand. She provides a lovely counterpoint to the busyness surrounding her.

Kumasi Market, painted in 1962, was a vibrant memory of Biggers’s visit to Ghana in the year of is independence, 1957. The Kumasi Market, sometimes referred to as Kejetia, remains a real destination (if you can’t travel there, you can watch YouTube videos of its liveliness). Home to over 10,000 stalls, the market sells everything from soap to beads, cooked food to fresh produce, hardware and tech goods, glorious fabric that can be turned into a dress by the time the sun goes down . . . you name it! It is a place of intense commerce, starting before dawn, ending at dusk. The Culture Trip website writes, “If you look beyond the crowded nature of things, the cacophony of business interactions, the miscellany of voices and items, the Kejetia experience is that of an interactive civilization and savoir-faire community where you will learn something at the end of the day.”

John Biggers’s artistic vision evokes the rich sensory experience of the market—not just the sights, but the sounds, the smells, the heat on skin. Biggers was drawn to this scene of vibrancy and productivity, perhaps seeing a strength in its existence that echoed Ghana’s recent empowerment. That might have been a connection shared by the former owner of this painting, Maya Angelou.

As I explore this work with our visitors, I am reminded of another work of art, one floor down: Luncheon of the Boating Party by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Once again, a large painting, and one that is crowded with figures.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-81, Oil on Canvas, 51 ¼ x 69 ¼ in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1923

The multitude of straw hats in Luncheon, provide a way for our eyes to move through the painting, as we unconsciously construct series of triangles out of the pops of yellow. The play of light also brings our eyes around the painting, picking up the glint of glass, the impasto of the uneaten bread, the sliver of sail boats in the background. And, the red and white striped awning, added by Renoir in his final stages of painting this large work, contains our eye, much like the architecture in Kumasi Market. Without the awning, our eyes might fly off into the distance.

And while not precisely central, Renoir’s love-interest, Aline Charigot, seems to command center stage with her rosy beauty and her festooned hat. Yet she cares little of us—her complete focus is on her puppy. She tunes out the noisy scene going on behind her, while as viewers, we are curious about her inner thoughts.

On one hand, we have American born and educated Biggers, inspired by the political events of West Africa. On the other, Impressionist Renoir was staying close to his French home with his French friends and yet their social activities were made possible by changes in French society.

These distinct artworks each reflect aspects of the social and political life that influenced the artists’ lives. When examined in relation to each other, John Biggers and Pierre-Auguste Renoir inspire us to consider the similar compositional choices and artistic techniques they each used; choices and techniques that bridge cultures, space, and time.