Visitors write letters for the To Future Women project at The Phillips Collection. Photo: Rhiannon Newman

To Future Women, Georgia Saxelby’s interactive piece honoring the one-year anniversary of the 2017 Women’s March, debuted at The Phillips Collection in February. The warm pink alcove papered with red and gray visitor responses and the circle of matching pink, high-backed writing desks presented a stark contrast to the earth-toned, heavy-framed Cubist works from the last century that lined the walls around it. Though the Valentine-heart color scheme evokes almost stereotypical notions of a “feminine” aesthetic, the presentation is anything but passive and soft. The conceptual prompt asked participants to consider what they would like to say to future women in the context of the recent and current socio-political environment that birthed the Women’s March and corresponding activist movements. Artistically, the installation speaks to the iconoclastic role of women in the modern and contemporary art world as well—a trend evidenced by recent Phillips acquisitions, several of which are currently on view.

Just outside the gallery where To Future Women was exhibited, visitors can currently see two works by feminist icon Georgia O’Keeffe. Different from her usual flowers and natural forms, both paintings feature architectural elements—an adobe chapel in New Mexico, and the painter’s own “shanty” at Lake George. About the latter, O’Keeffe was known to have joked that she painted it to prove that she could work in conventional, “dreary” colors as well as the men in her artistic circle. It is not hard to imagine her wry amusement at the fact that this uncharacteristically traditional composition in browns and greens earned the praise of her male critics who had been less than comfortable with the bold, vivid flowers that ultimately earned her a prominent place in the art world, not to mention at Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party.

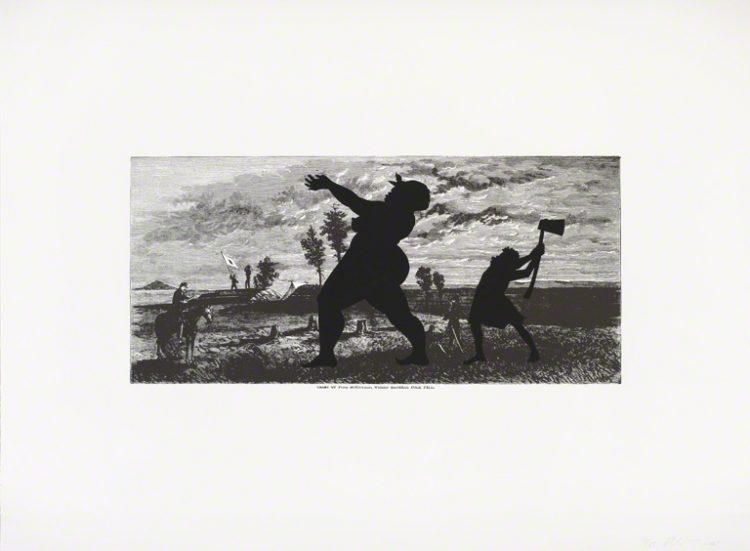

Kara Walker, Crest of Pine Mountain, where General Polk Fell, 2005. Offset lithograph with silkscreening Sheet: 39 x 59 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Gift of Julia J. Norrell, 2015

Of course, it goes without saying that women, like people of color and other minorities, have not received adequate recognition or representation in the art world. Apart from O’Keeffe, it can be difficult to find evidence of women artists among the 19th-and 20th-century impressionists, expressionists, and cubists. In one gallery, a single painting by Berthe Morisot hangs alone among works by Van Gogh, Gaugin, Monet, Bonnard, and Vuillard. However, among more recent acquisitions by the museum, art by women stands out and speaks loudly. Crest of Pine Mountain, Where General Polk Fell, a powerful work from Kara Walker’s Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War series, hangs in the same gallery as several panels from Jacob Lawrence’s iconic Migration Series. The faceless figures silhouetted in black against a background from a 19th-century issue of Harper’s Magazine about the Civil War speak volumes about both insidious stereotypes and the reality of African American experiences that still go unseen and unacknowledged to the detriment of American socio-political discourse. This is not just art by someone who happens to be a woman or a person of color—this is art that says something about the history and the experience of that identity.

Women are also well-represented in the collection of sculptural works on display at the Phillips right now. British artist Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture Dual Form provides a powerful focal point in the courtyard outside the museum café, and it is especially worth strolling up the central staircase to admire works by a number of contemporary sculptors—all women. Cuban-born artist Zilia Sánchez’s work Maquinista, Diptico, with its minimalist, mostly-white palette and subtle forms appears deceptively simple. At first, the play of shadows cast by the softly rounded shapes that rise to peaks like waves in a lake seems compelling, but non-representational. However, the pinkish-tan color suggests something more symbolic of the female body in a way that is conscious of itself and its natural shapes without being subject to external objectification. This impression is bolstered by considering the sculpture both in the context of the other works in the stairwell and in the context of Sánchez’s larger body of work. The Phillips will feature a solo exhibition of her work in 2019, and hopefully before the time capsule of Saxelby’s To Future Women letters are revisited in 20 years, many more groundbreaking women will find their art and their experiences represented in museums everywhere.

Rebekah Planto, Museum Assistant