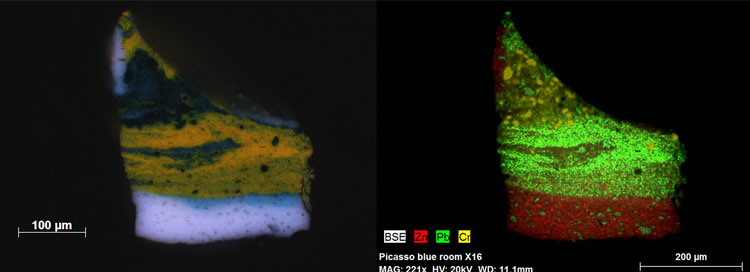

Left: Paint sample from Picasso’s The Blue Room (1901) showing how yellow, blue, and green paints were mixed while still wet to create a variegated effect. Right: X-ray map showing zinc, chromium, and lead-containing pigments. © 2014 Jennifer Mass, Winterthur Museum

There has been a lot of buzz this summer around the Phillips’s The Blue Room by Pablo Picasso, a 1901 painting created at a time when the young artist was trying on different artistic personalities. In June, an AP exclusive story revealed the image of an underpainting—hidden beneath the surface of the masterwork—uncovered by a team of scientists and conservators from the Phillips, Cornell University, National Gallery of Art, and Winterthur Museum. However, this discovery did not happen overnight. It is the result of many years of collaborative research between the four institutions to reveal details of the contemplative man painted in the hidden image and better understand Picasso’s materials and methods.

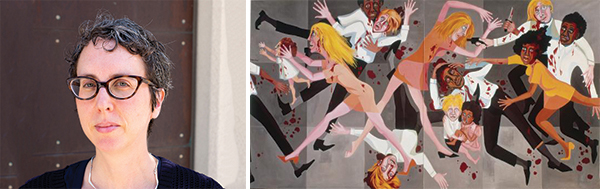

On Wednesday, the technical details of this scientific analysis were presented by Winterthur Museum’s Dr. Jennifer Mass at the Synchrotron Radiation and Neutrons in Art and Archaeology Meeting (SR2A 2014) in Paris. Her presentation addressed the palette and painting methods Picasso used for the two works and the relationship between those palettes. She also explored the wealth of information acquired through the combination of the cross-section studies, molecular analyses, hyperspectral reflectance imaging, and XRF imaging.

The Blue Room is currently being exhibited in an international exhibition at the Daejeon Museum of Art in central Korea, but the collaborating institutions will continue their research efforts as the museum prepares for a 2017 exhibition that centers on Picasso and this seminal painting.