On view in Pour, Tear, Carve: Material Possibilities in the Collection is a virtual reconstruction of Antoine Pevsner’s Construction in Space, a sculpture made of Celluloid which has changed over time.

Working with Plastics

Antoine Pevsner was born in Russia and immigrated to France in 1923. He worked in a Constructivist style, inspired by the increasingly industrial world. Pevsner and his brother, artist Naum Gabo, were pioneers in exploring new media. They became fond of Celluloid (cellulose nitrate) for its flexibility and transparency; Pevsner used it to make Construction in Space (1929). However, this plastic changes color and deteriorates as it ages. Both artists abandoned it in favor of more durable materials such as acrylic and glass.

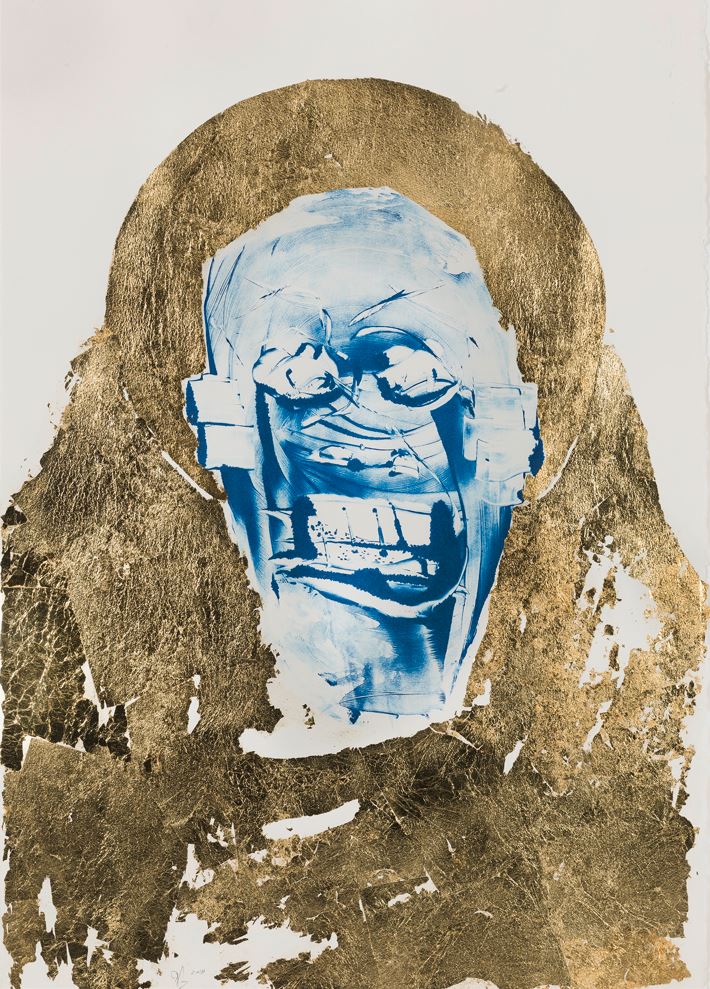

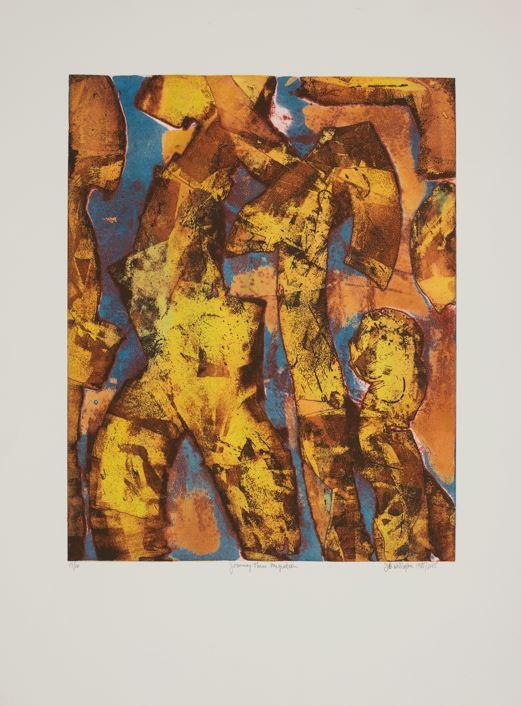

Left: Early photo of the sculpture before it began to decay. Right: Current deteriorated condition of the sculpture.

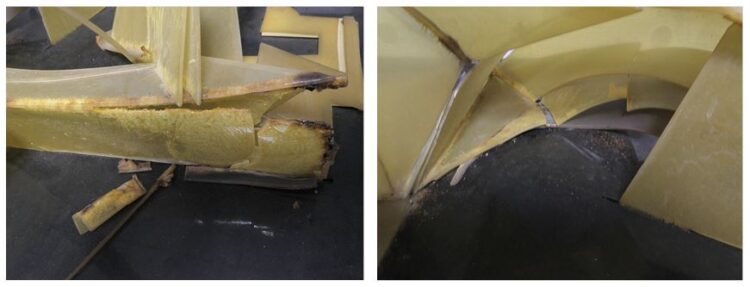

Close-up images of deteriorated condition

Deterioration

Duncan Phillips acquired Construction in Space in 1953. Three years later, when it was requested for an exhibition in France, Phillips noted the work’s fragility. The artist wrote to Phillips that if he sent the sculpture to the exhibition at the Museé d’art moderne, he would make the necessary repairs to the piece. The work went to Paris and repairs were made, but the plastic continued to deteriorate. In 1979, the work was sent to an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Conservators noted its severe discoloration and made repairs with yellow tinted epoxy to reinforce the once transparent object. Upon returning to The Phillips Collection, the object was placed in a wooden storage box and not shown again because of its poor condition. A handwritten note from 1987 indicates that pieces had “deteriorated” and it “needs re-gluing.”

Isolating the Sculpture

In 1996, conservators recommended isolating the object from the rest of the collection so that the acid off-gassing from the cellulose nitrate would not adversely affect other works in art storage. In 2015, a custom box was fabricated for Construction in Space and it was placed in a well-ventilated space in the storeroom with acid scavengers to absorb the off-gassing.

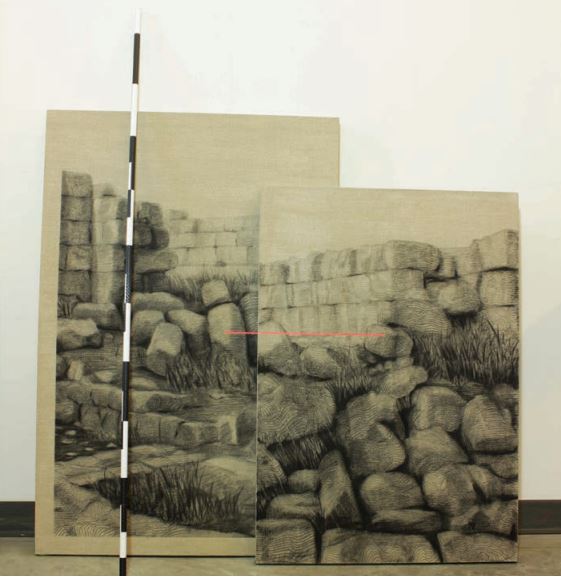

Inside of storage box with acid scavengers (long white bags). The green/yellow strips indicate the amount of off-gassing from the plastic.

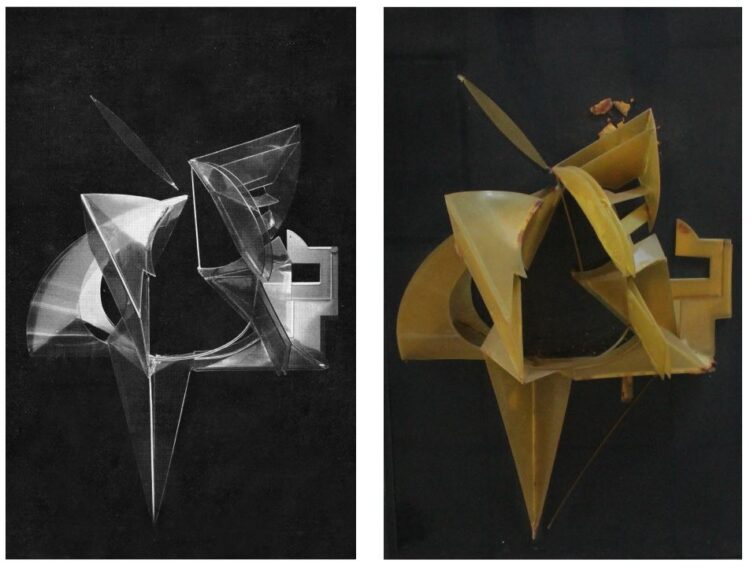

A Virtual Reconstruction

Because the sculpture cannot be restored or exhibited intact again, conservators decided to preserve the work’s original appearance by making a virtual replica. Stefan Prosky, a 3-D animator and technology artist, made a virtual reconstruction of the sculpture using 800 digital images of the work and also studying early photographs.