As any curator knows, the first important step in organizing an exhibition is creating and securing a checklist of works that perfectly illustrate the theme of your show, often from many collections in the US and abroad. At the Phillips, we receive dozens of requests for objects in our collection each year, and we do our best to accommodate as many requests as possible while maintaining the integrity and security of our works. Lending our beloved collection to venues around the world increases the Phillips’s exposure to populations not familiar with our institution and allows us to form and strengthen relationships with museums and galleries.

When we receive a request for an object in our collection, our conservators first check the condition of the object to assess if it is stable enough to travel. They also factor in how frequently the work has traveled recently and condition reports from requesting museums (which indicate security measures, gallery conditions, light levels, etc.). Once the work has been OK’d to travel by our conservators, the request is then discussed in a quarterly meeting with the director, curators, and registrars to see if the request conflicts with any upcoming exhibition or installation plans. If the work is approved to travel during that meeting but has a high insurance value, it will then go to the board for approval. Otherwise, once the work has been cleared by curatorial, preparations begin for its travel.

Over the past few years, a few works have become very popular and have racked up quite the number of frequent flier miles and requests. It may come as no surprise that we receive regular requests for our Luncheon of the Boating Party, van Goghs, Bonnards, and O’Keeffes, but some popular pieces may surprise you.

While many of our masterpieces have accumulated stamps in their passports the past few years, few have traveled or been requested more than the current “it” girl of The Phillips Collection, Oskar Kokoschka’s Portrait of Lotte Franzos from 1909.

- Oskar Kokoschka, Portrait of Lotte Franzos, 1909. Oil on canvas. 45 1/4 x 31 1/4 in. (114.9 x 79.4 cm). Acquired 1941.

Number of requests since 2000: 22

Recent travels:

- National Gallery, London, “The Portrait in Vienna, 1900,” October 9, 2013-January 12, 2014

- Neue Gallery, New York, “Vienna 1900: Style and Identity,” February 3, 2011 – June 27, 2011

- Wellcome Collection, London, “Madness and Modernity: Mental Illness and the Visual Arts in Vienna 1900,” April 1—July 14, 2009

- Reunion des Musées Nationaux (Grand Palais/Musée d’Orsay), Paris, “Klimt, Kokoschka, Moser, Schiele,” September 1, 2005—February 1, 2006

I recently had the privilege of escorting Lotte back from an exhibition in London this past January, and even though her expression may read a bit world weary (jet lag can be brutal), I can assure you all the travel has not diminished her vibrant beauty. Due to the large number of requests she’s getting, it’s safe to assume that this evocative portrait has risen to a new prominence in Kokoschka’s oeuvre.

On the subject of traveling across international borders: most seasoned travelers know that when flying between countries, there are certain food products that will get held up at customs. Specifically, in many cases, cured meats. However, painted depictions of such contraband are not subject to those rules. Which brings me to….

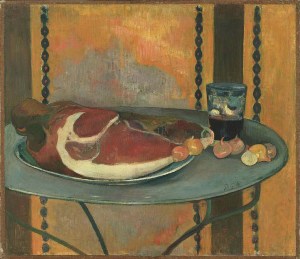

Paul Gauguin‘s The Ham, recently back from a Gauguin retrospective in Korea. What more can one say about The Ham that hasn’t already been said here, here, and here? It’s….a ham. Albeit, a gorgeously depicted one. This work, already a favorite amongst Phillips staff, has become quite popular with 11 requests from international and domestic institutions in the past 10 years. I guess you could say other museums are hungry for a piece of this delicious masterpiece! Apologies, but I had to say it.