Curatorial Intern Jason Rosenberg on his experience at the opening of Marta Pérez García: Restos Traces.

White walls and silence: across all the museums I’ve visited, these have been the unifying attributes. This familiar atmosphere of peace and introspection provides a powerful juxtaposition to the vibrancy of the works on view; by removing all distractions, a deeper level of understanding can presumably be more easily achieved. And yet, this set-up always felt characteristically out of place—somehow at odds with the lively scholarly debates endemic to the evolution of the art historical field. If the entire purpose of art is to spark dialogue and call attention to pressing societal issues, why are audiences being so quiet?

Joining The Phillips Collection this spring as a Curatorial Intern, I longed to be a part of an institution actively working to shatter this passive normative practice in the art world. Given the opportunity to professionally shadow the Director for Contemporary Art Initiatives Vesela Sretenović, I quickly recognized our shared connection and desire to make art accessible—envisioning a world in which exhibitions stay open far past 5 pm, feature texts understood by all skill-levels, and promote a bustling immersive communal experience within the confines of the gallery and beyond.

Having little to no prior experience to go off of, I attended my first exhibition opening this past March. Throughout the planning and installation process, I began to recognize the series of variables that need to align in order for an event like this to be successful. The Intersections project Restos-Traces by Marta Pérez García centers around a series of nearly 20 headless female torsos—many of which are in muted in color and altered to comment on the prevalence of domestic violence. I wondered: how would audiences react? Would the room be celebratory or somber? Would people show up on a Thursday night?

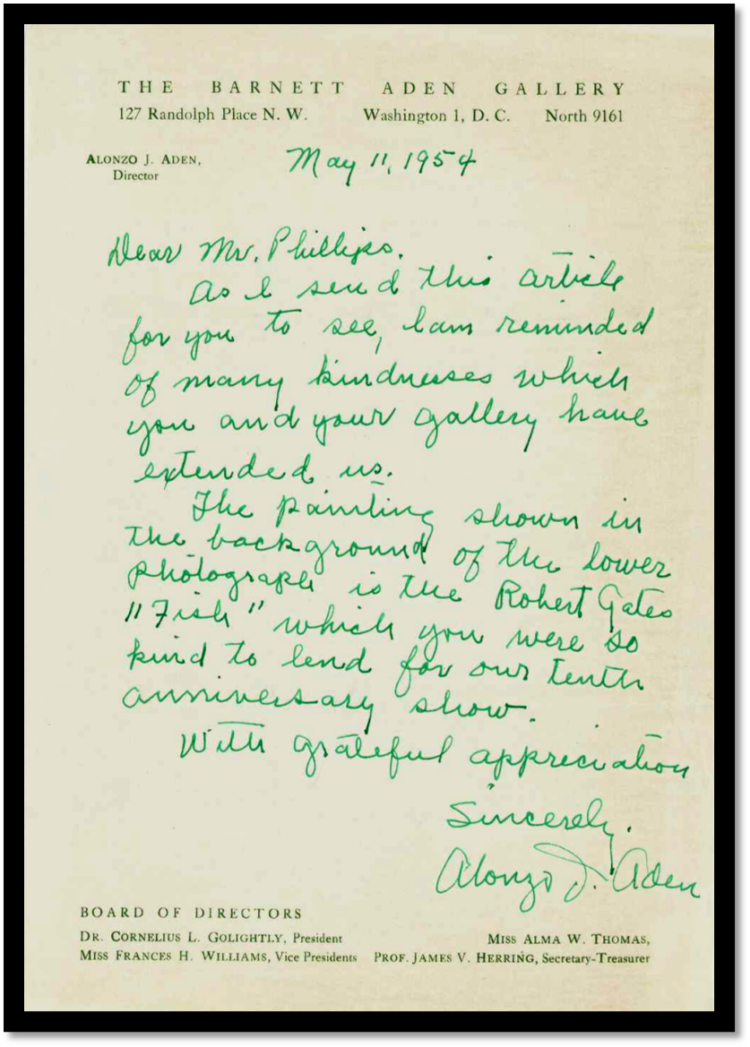

Marta Pérez García and Jason Rosenberg and scenes from the exhibition opening

Surrounded by cups of white wine and dozens of strangers in suits, I quickly realized there was no reason to worry. Making my way through the bustling crowds of lively and diverse groups of visitors in attendance, all pretenses began to dissipate. The once banal white walls were substituted with Pérez García’s work hanging from the ceiling; silence was replaced with staggering conversation; audiences interacted with rare cordiality. As my mentor and exhibition curator Vesela interviewed the artist, I began to see the profound impact one’s research and hard work can have on otherwise disjointed populations. Joining the crowd in awe, I caught a glimpse of what museums have the potential to be: a place of widespread connection and celebration.

As a first-time attendee, this opening celebration was of special personal significance from the get-go; after years of studying artistic theory through textbooks, it felt surreal to watch a living artist debut their work in-person. No longer did I need to flip through heaps of journal articles to answer a question; there was no need to track down secondary sources. Rather, I was living through the history—the artist was alive and present. Like many others that night, I felt part of something greater; despite being strangers, our shared collective passion for the arts was able to transcend through trivial boundaries and foster a rare environment of unity.

As the first fully in-person Intersections opening following the onset of COVID-19, this gathering signified a powerful spirit of resilience; like García’s encircling torsos, Restos-Traces embodies perseverance and endurance through one’s circumstances, acknowledging humility and a desire to smile along the way.