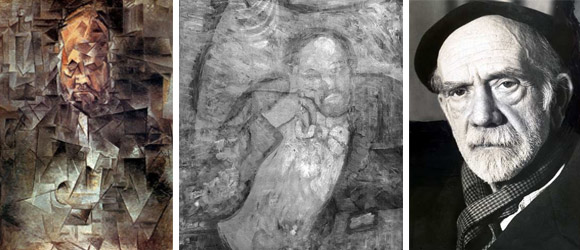

Images, left to right: Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1910. Pushkin Museum of Fine Art, Moscow, Russia; Infrared of Pablo Picasso’s The Blue Room (1901). The Phillips Collection, copyright 2008; Pío Baroja, photographed by Prieto.

After discovering a hidden painting underneath the Phillips’s The Blue Room (1901) by Pablo Picasso, conservators and curators are still researching the identity of the person in the portrait. You’ve been calling, e-mailing, tweeting, and posting your ideas about who the mystery man might be. We’re sharing information on the most popular suggestions here on the blog. Today, we focus on Ambroise Vollard and Pío Baroja.

One of the most frequent suggestions continues to be Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939), a foremost European art dealer at the turn of the century. Known for his keen eye in recognizing rising stars, he amassed an impressive list of artistic connections, including Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, and Vincent van Gogh. Vollard boasted the first one-man exhibition of Picasso’s work, and in fact the artist did create a portrait or two of his dealer during his lifetime. However, this was not a terribly uncommon practice. One Phillips patron wrote in noting that the small lips, body language and type, as well as outfit seem very similar to other portraits of Vollard.

Another name that has come up several times is Pío Baroja (1872–1956). Baroja was a writer best known for his seminal work The Tree of Knowledge. While his novels never reached the height of popularity, likely due to his penchant for pessimism, he is still considered one of the leading Spanish novelists of the period. Baroja was a member of the Generation of ’98, a group that lead the way in avant-garde change in Spain and which paved the way for artists like Picasso. A Phillips follower tweeted that Picasso drew him for Arte Joven while in Madrid.

We want to hear your thoughts! Send us your suggestions for who the mystery man may be with #BlueRoom or in the comments below We’ll collect the most popular (and some of our favorites) on the blog over the next week.