This month’s members’ magazine includes a new feature called “From the Archives” and our first selection focuses on Duncan Phillips’s love of Giorgione and his related exchanges with scholar Bernard Berenson on issues of attribution.

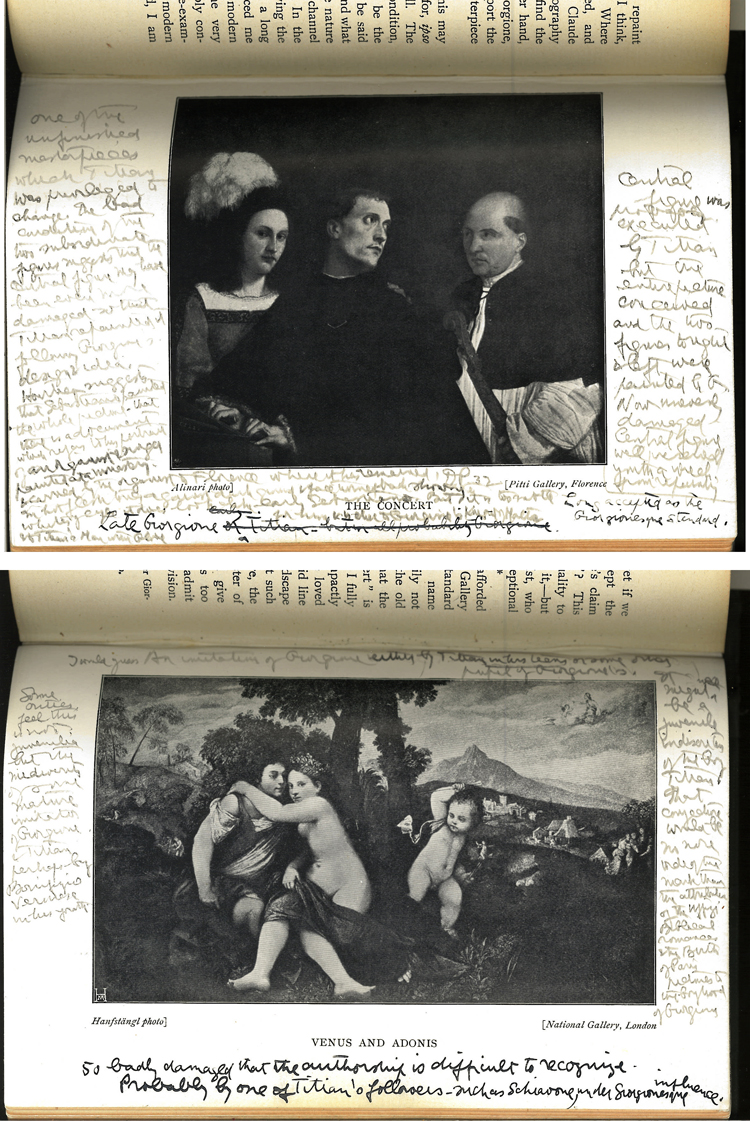

Heavily annotated plates in a 1907 printing of H.F. Cook’s Giorgione, from the library of Duncan Phillips.

I have written before about Phillips’s prolific marginalia. I do not write in my books, but having come across, and even relied upon, so many of Phillips’s notes, I wonder if I shouldn’t start having these conversations with text. A couple of years ago, Sam Anderson wrote a wonderful essay in The New York Times Magazine about how he came to be a devoted writer of marginalia:

Today I rarely read anything—book, magazine, newspaper—without a writing instrument in hand. Books have become my journals, my critical notebooks, my creative outlets. Writing in them is the closest I come to regular meditation; marginalia is—no exaggeration—possibly the most pleasurable thing I do on a daily basis.

Anderson goes on to lament the shift to e-readers, clinical devices without the same sense of ownership. Do they mean the end of a reader’s ability to energize their experience of text by recording their responses, creating a dialog? In the end, Anderson comes around, re-envisioning marginalia as, in fact, a very current way to communicate. What else is Twitter but a giant collection of in-the-moment responses, musings jotted in the margins of real life? (And in a bit of a meta twist, Anderson sometimes tweets images of his marginalia!)

Phillips enjoyed intellectual engagement—with others, with himself, with text. His marginalia can be some of the most revealing resources available on this private man. If he were alive today, would he take to Twitter, sharing his arguments and considerations in 140 characters, as opposed to hiding all of those ideas in the pages of books and the backs of brochures? If he thought he could find a worthy audience, I think he might.