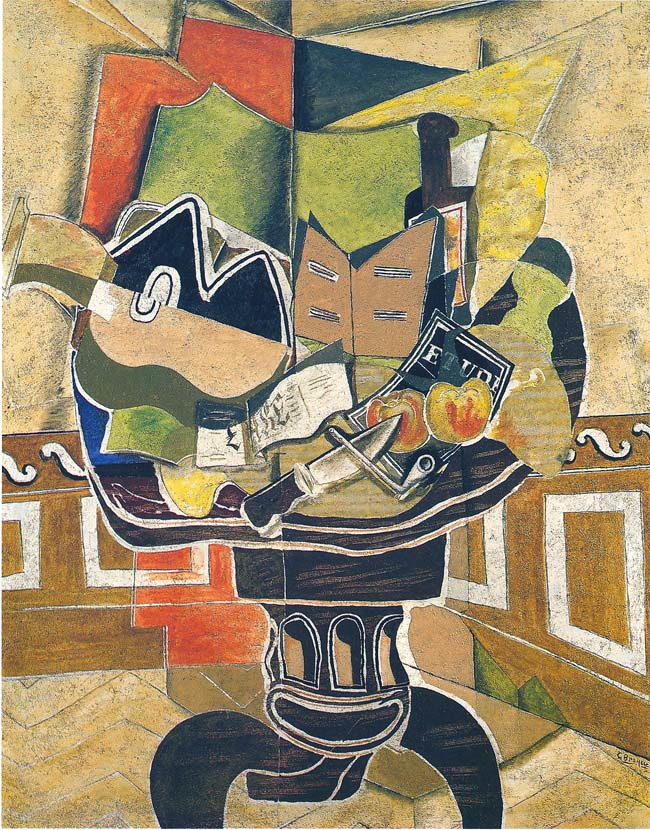

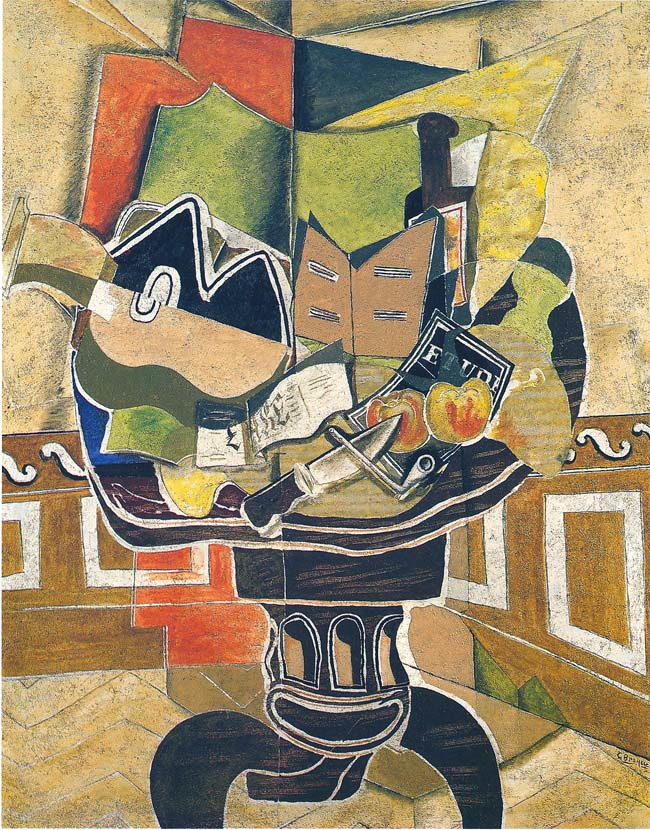

Georges Braque, The Round Table, 1929. Oil, sand, charcoal on canvas, 57 3/8 x 44 3/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1934 © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

A few weeks after the exhibition Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928–1945 opened, I incorporated a quote by Duncan Phillips into my tour of Braque’s The Round Table. It’s from his 1926 book A Collection in the Making.

“No matter how sound the museum director’s policy of ‘playing safe,’ there must be collectors bold enough to make mistakes while encouraging development and progress…. I cannot resist the temptation to introduce a few of these challenging young artists in our midst.”

When Phillips added The Round Table to his collection in 1934 it was the largest, most abstract, and what some considered the most challenging work he displayed to date.

After I read this quote, I invite viewers to spend a minute or so looking closely at The Round Table and thinking about what they see in the painting that might be challenging. The most common responses are:

- Perspective – some do not see any perspective; others see many different perspectives

- Size

- Colors

- Objects on the table look like they are about to fall off

- Combination of abstraction and figuration

- Cubist elements

- Texture

- The round table isn’t round!

Watching the visitors look for the challenges in Braque’s work and listening to their responses, I have noticed a change in the overall reaction to The Round Table. Many more visitors react positively, and as they share their ideas with the rest of the group, I can often see the satisfaction they feel in rising to the challenge of Braque’s work.

Sometimes we see a challenging work and dismiss it without digging deeper. Since I began my graduate studies in art history at George Washington University I have tried harder to unpack challenging works, or what some refer to as “meeting the work halfway.” It is not always easy, but I think it is worth the effort!

Beth Rizley Evans, Graduate Intern for Programs and Lectures